May 20, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

Coriolanus (Stratford Festival) @ Stratfest@Home (webcast)

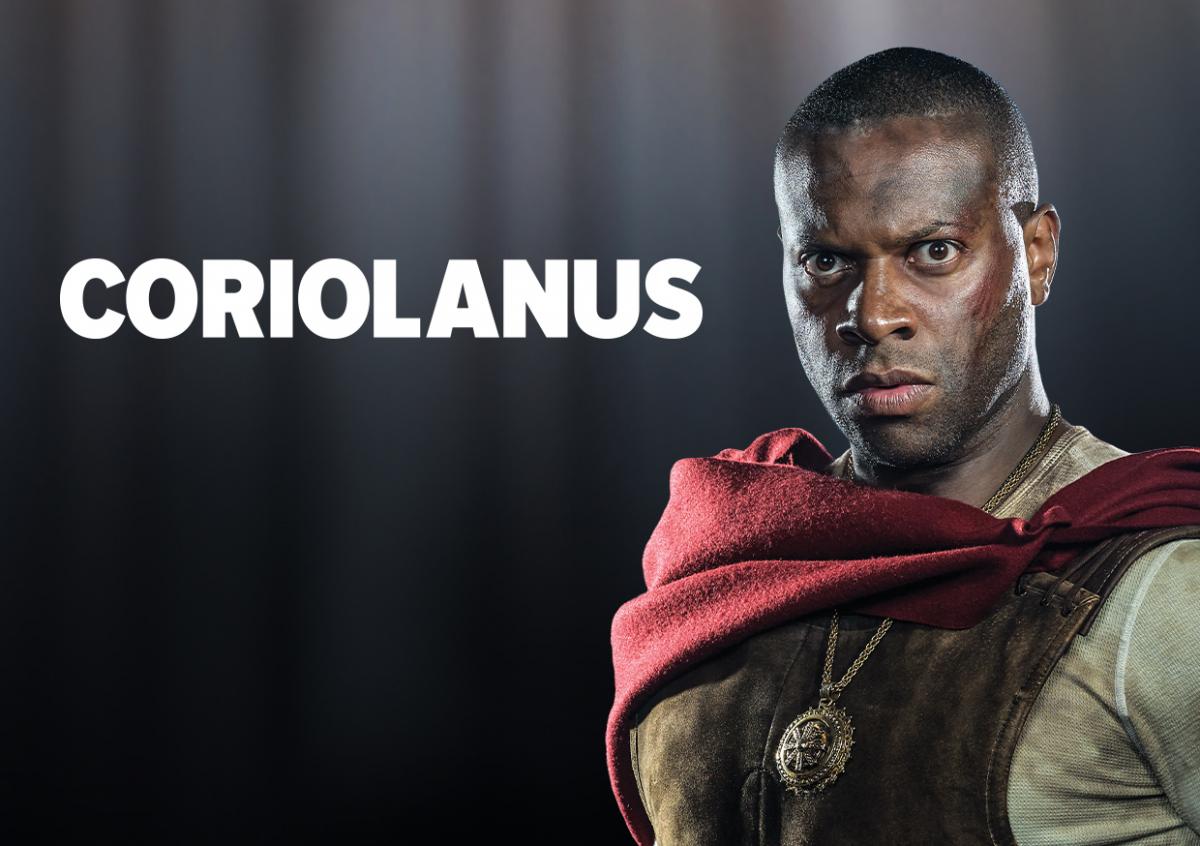

There’s a near-perfect alignment between form and content in Barry Avrich’s film of Robert LePage’s Coriolanus, originally directed for the Stratford Festival, Ontario in 2018 and now broadcast live internationally via Stratfest@Home. Perhaps almost too perfect. LePage’s Coriolanus is fully committed to its formal conceit, even at the expense of rendering the production almost entirely two-dimensional – which at times just feels flat. But with a sympathetic direction for screen, the production’s nuances and points of interest, for better and worse, find a natural home.

Manuel Jacquez’s Shakespeare Bulletin review discusses in detail the production’s attempts to recreate filmic effects on stage, including moving frames that create the effect of split-screen or closing shutter windows, and with a primary camera situated dead-on at the back of the theatre’s auditorium, allowing the stage space to perfectly fill the frame, the recreation of film is uncanny. Many of the scenes take place in small, contained, detailed naturalistic sets, that slide on and off a pitch-black stage to give the effect of a tiny window of action within a screen. For larger sets, a dynamic set of shutters allow the image to unfurl into visibility, and then to close off at the end – the production’s final shot has the shutters gradually cutting off the space to draw focus onto Aufidius’s grieving face, the last thing that remains visible before they finally close. The framing of this from the camera at the back of the auditorium shows how impressive the effect is, completely flattening the mise-en-scene and at times looking like a genuinely filmic effect. The lines are blurred further in the screen version by the imposition of intertitles and captions detailing the Act and the location, and by a full screen-only credits sequence after a prologue. It’s a thorough remediation that is sympathetic to the production’s own aesthetic.

And remediation is central to this production itself. We’re dealing here with legacy: the opening image is of a bust of Coriolanus’s head, as if in a museum, which suddenly comes to life and starts speaking, André Sills’s face projected onto the haughty statue to speak his own legacy. This is one of the few technical tricks that works slightly less well in close-up, but it introduces a production centered on the various ways in which legacy and reputation are transmitted. 1.1 is played as a radio phone-in, with Menenius (Tom McCamus) defending Caius Martius against detractors and calling for reason, even while the host and another guest bait him. In a modern political world of cameras, news broadcasts, hot takes and media frenzy, the politician has to always be ready with a soundbite – in one glorious moment later, Menenius breaks away from calming Martius down to quickly smooth his hair and give a quick interview to a hopeful reporter.

The world of this Rome is a contemporary and recognisable North American political milieu. Senators and tribunes alike are a group of interchangable, indistinguishable, middle-aged white men, and they run the nation out of the Capitol bar, tiny offices (Sicinius (Tom Rooney) and Brutus (Stephen Oulmette) are seen frantically calling supporters from a shared room) and restaurants. LePage’s sets are richly detailed, and full of loving touches – one especially nice gesture sees one of the tribunes throwing darts at a wall in his office that thud into a board perfectly aligned with the head of Martius, standing with his back against the wall of the neighbouring office. It’s a neat touch that emphasises the claustrophobia of the political environment, which threatens to erupt into violence.

The violence is innate in the play. While the war scenes are cut down, there is enough to show the effect they have had on Martius. Far from adulating in the war, he seems broken by it even while on service. When Cominius (Michael Blake) comes to give him the news of his victory and celebrate his new name, Martius is shaking, bloodied – and when someone walks in too quickly, he leaps up with a knife, ready to kill, and Cominius has to talk him down. Martius is in a fight-or-flight state from the start of the play, with little appetite for flight, and even when he is welcomed back to Rome (in a truly spectacular visual imagining a plane landing and him descending onto a windy airfield) he remains tense and jumpy. The service he has done for Rome has left him with scars.

The casting is colour-conscious – it’s no accident that Martius and Cominius are played by powerful Black men, while the other politicians are all older and white. This is a political culture that is happy to send its Black men off to war and to celebrate their victories – but which, as soon as one of those men strays out his lane and is pushed towards politics, closes ranks against him. It draws loaded attention to the emphasis on Martius’s body, the parade of the soldier as an example of strong, enduring physicality in service of the state. And at the play’s end, Aufidius’s insult of ‘boy’ to Martius is what tips Martius over the edge, he repeatedly roaring ‘Boy?!’ in reply as he barrels towards his death. Reading Martius’s treatment as institutional racism feels especially pertinent in the ongoing rank-closing in North American primary elections, especially as we head into yet another old white man double-header of a US election; there is no room for Martius as a consul here.

Read in this way, Martius’s public banishment is inevitable, and takes its time coming. Menenius acts like Martius’s minder, running interference for him with the press and staff, but Martius feels increasingly trapped. When the press begin hounding him, he at one point grabs the ceremonial sword that has been mounted on his wall – no longer intended for us – and begins swinging it in the confined space of the office and corridor as he attempts to get at Sicinius and Brutus but is wrangled away by Capitol security. Forced to account for himself at dinners and hearings, Sills’s Martius is ill at ease, blinking in the glare of the camera lights, desperately constrained by suit and convention. Sicinius, by contrast, employs another Black man to secretly rile up the crowd against Martius; then, when it is his turn to speak, he steps forward and makes a long, confident ritual of cleaning his glasses before starting to speak. Everything Martius does, he is forced to do on the terms of the existing system, which is designed to deliberately exclude someone who is unfamiliar with its workings – a point Martius makes forcefully as he overturns the podium and roars ‘I banish YOU’ upon his banishment.

It’s at this point that Martius appears to embrace an identity other than the one he has been performing for the sake of Rome. Donning a do-rag and slacks, he kisses his family goodbye and gets into a car – which, in a whizzy bit of back-projection, appears to accelerate through the city, a tunnel – and, with a blink as if he’s momentarily fallen asleep, a forest – before arriving at Antium (the fact that the car can do all of this in a single straight line does look a little silly, but the effect of the tunnel lights in particular is magnificent, with credit to Laurent Routhier’s lighting). The contrast between Sills’s brooding face in the long driving scene, now in casual clothes and isolated, and what’s left behind in Rome is stark. Menenius continues to have bitter disputes with the tribunes over whiskey in the bar; they hate one another, yet they still share the same space. And Volumnia (Lucy Peacock) is embarrassed to be out in public. In a cheap gag, she goes out for dinner with Menenius and Virgilia and refuses to eat, saying ‘Anger’s my meat’ while throwing a menu back at a puzzled waiter who looks at Menenius for guidance. While this renders an important line over-literal, the sight of Volumnia losing her shit in a fancy restaurant while other diners look on critically is a reminder of how much she had at stake in her son, and how much she has lost.

There are a few too many cheap jokes. The conversation between Adrian and Nicanor is played with two men standing back to back texting one another, their text conversation appearing on the wall, with one sending an emoji at the other’s smutty joke; it’s an easy laugh (though I confess I did). But it speaks to a drift in focus in the production’s second half. Part of the difficulty is that Aufidius (Graham Abbey) never feels fully fleshed out – in such a carefully controlled production, which represents the fighting via Martius’s son playing with toy soldiers while Martius and Aufidius’s physical confrontation is sidelined, Aufidius’s physicality is reduced and so he becomes a much broodier, talky character, given to long monologues that slow down the action. He’s a bit too much of an enigma, his quiet resentment at Martius (shown when he and his lieutenant, Johnathan Sousa, sit together in a house and watch fireworks to mark Martius’s arrival) not developing beyond what is absolutely necessary. And the awkward play-wrestle when Martius first reveals himself to Aufidius feels forced and perfunctory, the sudden physical intimacy not tied sufficiently to the rest of the performance.

The women and people also feel sidelined in this production. There’s an impressive set for the first scene between Volumnia and Virgilia (Alexis Gordon), the two framed behind an enormous loom as they weave quietly together. Virgilia is pregnant, a fact she reveals to Valeria (Brigit Wilson) as her explanation for not going out with them, as if pregnant women obviously aren’t allowed outdoors, and does some excellent subtle work stroking Martius’s arm and supporting him as he sits in obvious discomfort while Cominius sings his praises. But the climactic scene of the women meeting Martius as he invades Rome is the one that suffers most from the flattening of the action, looking stilted with the top half of the stage in blackness that weighs down upon them and stifles the relations between the family. The common people too are largely cut, with no crowd scenes. Martius’s display of himself in the market is played as a door-to-door canvassing scene, which rather mutes the populism, though allows Wilson a great performance in sign language as Martius – patiently, for him – attempts to communicate his service through an interpreter, leading her to approve of him.

It’s a production full of ideas and spectacle. and the exploration of racism within national politics is potent; it’s a shame, then, that the production seems to lose interest in its own best ideas. The conclusion wraps things up fairly abruptly, with Martius wrestling Aufidius onto a bed and Aufidius’s lieutenant shooting him cursorily through the back of the head, Martius’s body frozen briefly before slumping down on top of Aufidius. The fact that Sills is then invisible, hidden by the base-board of the bed for the rest of the scene, feels like a real error of judgement, especially as the shutters of the on-stage frame then close around Aufidius, weeping next to the bed, inviting us to … care? The production values are impressive, but like Martius’s body, the production sometimes risks forgetting about the people at its heart.

Many thanks to Christie Carson for discussions of the production in the run-up to this viewing.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply