July 16, 2019, by Peter Kirwan

Screening The Royal Shakespeare Company: A Critical History, by John Wyver (Bloomsbury, 2019)

The Royal Shakespeare Company’s relationship with film stretches back to the very earliest days of that medium, with Frank Benson’s two-reel film of Richard III – now a staple of university Shakespeare On Film courses – shot on stage at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon; meanwhile, the company’s ongoing commitment to broadcasting its main stage productions of Shakespeare to cinemas around the world mean that it is developing one of the most substantial twenty-first century corpora of filmed Shakespearean theatre. Yet few scholars have taken the long view of how the Stratford company’s history has both shaped and been shaped by its engagement with the screen, and this is where John Wyver’s essential new book comes in.

Wyver’s book is subtitled A Critical History, and this book is indeed a careful, richly detailed and painstaking work of history. While some of Wyver’s materials are readily accessible – including those few RSC productions that were converted into cinematic films, such as Peter Brook’s King Lear, as well as the more recent productions widely available on DVD – the complex world of television archives, especially of ephemera broadcast once and never otherwise disseminated, is more specialist. As a professional television producer, Wyver brings his unique expertise to bear in setting out the rich array of screen traces of the RSC and its Stratford forebears, making this book an important resource for stimulating further work in this area, as well as providing the context for these films, documentaries, and excerpts.

Structured chronologically, the book works through several periods of the Stratford company’s history, focusing on well-chosen case studies and tying the company’s experimentation with cameras to the broader history of its emergence as a company, and in doing so offers a useful update of the earlier histories of Stratford by Sally Beauman and JC Trewin. Key to the first chapter is an understanding of the concerns around competition and value that shaped the Stratford company’s tentative early engagements with screen. Benson’s Richard III, Wyver argues, was likely shot in the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre precisely as part of the strategy to legitimise the new medium (11). Later, however, the advent of television brought with it concerns over the competition with theatre at large, and strict regulations on how much of an existing show could be shown on television. The BBC enters the story at this point, and it’s interesting to see how a relationship that would prove to be so mutually beneficial in later years started with a great deal of caution, leading eventually to the broadcast of the second act of The Merry Wives of Windsor in 1955 prompted partly by the emergence of ITV with its ‘American-style’ programming (26).

Other media and companies are tangential parts of Wyver’s narrative in the early years. The focus on the RSC is a (necessary) limitation, and Wyver’s note that cameras were more regularly gracing the stage of the Old Vic in the early years of television – Stratford being somewhat too out of the way – is an important reminder that there are larger narratives about the relationship between theatre and the screen in the UK that this book does not tell. Radio, too, emerges as an important context in the early twentieth century, and Wyver gestures briefly to the RSC’s turn to audio recordings before the arrival of television; again, this isn’t the story being told here. But as the christening of the new Royal Shakespeare Company arrives in the 1960s, along with Peter Hall’s pragmatic approach to the role of Artistic Director, film immediately assumes a significant place in the RSC’s plans.

Chapter 2 is centred on The Wars of the Roses (1965), repeatedly trailed earlier in the book as one of the finest stage-to-screen adaptations, and the account of both the logistics of the undertaking and of the film that resulted is a highlight of the book. Wyver’s writing is at its best in his deft, efficient explanations of the recording process, giving detailed accounts of filming restrictions (for example, the relative unavailability of zoom lenses owing to the BBC’s commitment to soccer, jazz, and ‘the Whitehall farces’, leading to rare uses of zooms in the finished film (p.52) and the techniques used in production. What is a little more lacking outside of very select case studies is detailed examination of the film productions themselves; Wyver gives great descriptive detail of documentary shorts and other ephemera, recounting the various snippets used in (for example) the BBC’s Sunday Night, but when it comes to describing recordings of productions such as The Cherry Orchard, As You Like It and All’s Well That Ends Well in the 1960s, there is a little too much qualitative celebration of the opportunity to see great actors of the period, when what is most interesting is Wyver’s insightful analysis of the burgeoning techniques and formal experimentations in capturing stage performance undertaken by these productions.

Chapter 3, focusing on the decade from 1964-73, is a chapter of two halves. The first is a beautifully told behind-the-scenes history of the early RSC’s financial entanglements with Hollywood, including in Peter Hall’s deal with the American production company Filmways. The main characters in this are Hall, RSC governor Michael Birkett, wunderkind director Peter Brook and venerable actor Paul Scofield, and the drama is one of budgets and contracts, in which Filmways snapped up the RSC for three film versions of RSC productions and a seven-year option on future films, a deal which produced Brook’s film of Lear and the production of Peter Hall’s 1969 Midsummer Night’s Dream, which received lacklustre notices in both the British press and in Wyver’s own analysis, though he is generous enough to note the subsequent praise the film – amateurishly made, but interpretively exciting – has had from academic quarters. The hope was that Hollywood’s dollars would help the struggling company, which ultimately would not be the case (63), and Scofield’s withdrawal from a film of Macbeth based on a production he didn’t like helped scupper the deal. The second half of the chapter focuses on Brook’s films of Marat/Sade, Tell Me Lies and Lear. Here, Wyver reminds the reader of the enthusiasm for British art film in this period, and while Wyver speeds through the three films, what emerges is the contemporaneity and political urgency of the version of the RSC Brook developed in these films, even as they shift quite substantially away from the theatrical stylings of the shows they were based on.

The conclusion to Chapter 3 also offers a pleasing moment of original archival detective work, as Wyver challenges the narrative that Brook’s Midsummer Night’s Dream was not recorded, tracking down no fewer than three partial recordings of variable quality. More interesting than the survival of clips and near-complete performances, however, are the methodological underpinnings and reminders of the nature of evidence, with Wyver distinguishing between recordings of screenable quality and what is useful to the historian. This section, along with other parts of the book, is also a potent reminder of the sheer variety of the way in which RSC productions have been preserved – the hi-resolution, full production capture is a rarity, but the number of rehearsal clips, publicity shorts, documentaries, interviews and touring records can collectively preserve a surprising amount of an ‘unfilmed’ production.

The seventies form the basis of Chapter 4, covering the Trevor Nunn and Terry Hands years. The title ‘Intimate Spaces’ foregrounds what is, for Wyver, one of the finest RSC screen adaptations – the 1979 Macbeth starring Ian McKellen and Judi Dench – but also includes discussion of important but historically forgotten productions, such as the 1972 Miss Julie, shot with multiple cameras in a 330-seat auditorium with ‘subtle enhance[ments of] the stage action with expressive framings, limited but telling camera moves, dissolves and occasional rapidly cut sequences’ that Wyver identifies as an important precursor of NT Live and Live from Stratford-upon-Avon’ (103). The story that emerges during the Nunn/Hands years is one of commercial collaboration, with experienced television directors joining Nunn on his versions, laugh tracks being added to The Comedy of Errors (1978), and production company ATV entering into a partnership that started producing much more regular full-production versions than at any point hitherto. Channel 4 also emerges as a collaborator in an extended case study of Nicholas Nickleby (1982), the first programme commissioned for the new channel – like The Wars of the Roses, another era-defining project that attempted to show the RSC’s resources at their full extent.

The final two chapters bring the story up to the present, covering 1982 to 2012. Wyver follows the conventional narrative of seeing the reigns of Terry Hands and Adrian Noble as a time of ‘existential crisis’ (131) followed by the stabilising tenure of Michael Boyd. Familiar here are stories of the rise of a new generation of leaner classical theatre companies (including Cheek by Jowl, of this parish), the controversy over the RSC’s withdrawal from London, and the ongoing financial troubles. But Wyver also points to the comparative lack of interest in filming theatre between those three directors as part of the reason that the ‘public memory’ of the RSC’s work during this period is comparatively sparse, and a recurrent theme of the book comes into focus – that the partly-commercial, partly-artistic motivations for filming the RSC’s productions were also instrumental in constructing the narrative of the company’s history, for itself as much for a broader audience.

Wyver traces several narratives of potentially large-scale deals, including one with RKO-Nederlander which allowed for as many as four filmed productions a year; an arrangement which resulted in only one film, Cyrano de Bergerac (1985). Later that year, productions of Moliere and Tartuffe represent what Wyver calls the ‘endgame for single plays made in television studios with multiple electronic cameras’ (137) as the market for stand-alone dramas with theatrical origins gave way to more serialised and location-based content. At the same time, the Swan remain undeveloped as a potential venue for filming. However, the company’s policy of creating archival productions kicked in during the 1980s, beginning the process of visualising the company’s memory in moving image in a more (though never entirely systematic) way). Even here, though, Wyver gives lie to the idea that these are merely passive, fixed-camera affairs, pointing to the 1985 recording of Adrian Noble’s Henry V where the camera operator pans, zooms, and even offers interpretive flourishes (144).

The major films that emerged from these years regrettably did not include a mooted film of Michael Boyd’s Histories Cycle, and indeed the golden era of cinematic Shakespeare had arrived by that point, with changing expectations (Wyver notes that The Hollow Crown perhaps filled the gap that Boyd’s Histories might have filled, and more obviously designed for the screen). Indeed, Adrian Noble’s 1996 Dream represents the last time the RSC turned one of its productions into a cinematic film, compared unfavourably with its limited budget and stylised variables to The Big Breakfast by one reviewer (149). Other films from this period such as Greg Doran’s Macbeth and Winter’s Tale and Nunn’s Othello represent the last flourishes of the strategies during Nunn’s artistic directorship. However, Wyver gives space to the emergence of different kinds of screen iteration of the RSC, such as performance paratexts including trailers, and the filming of two productions from Boyd’s tenure by Digital Theatre, setting up the current state of play in Stratford.

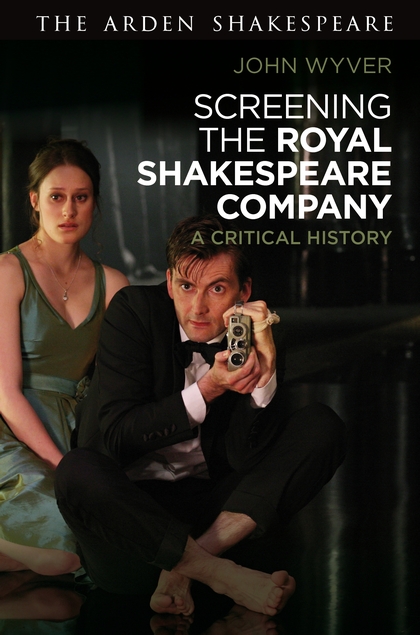

Gregory Doran, in Wyver’s view, is the first RSC artistic director to commit to an integrated broadcast strategy, initiating the Live From Stratford-upon-Avon series of live broadcasts and subsequent DVD releases, and putting the company’s ‘nowness’ back at the heart of its mediatisation; in this, in some ways, coming full circle back to the start of the book. Wyver acknowledges his own investment in this period at the heart of producing the RSC’s screen identity, and the personal tone is welcome in this part of the book, particularly as Wyver articulates his own frustration that what he and Doran felt was the outstanding creative success of the filmed version of Doran’s 1999 Macbeth – capturing the ‘raw energy and dangerous intimacy’ of the stage production – did not establish further interest from television companies in expanding this aspect of the company’s work. Here, too, Wyver’s insider status allows him to offer a huge amount of detail about, for example, the rationale and practicalities informing the development of the 2009 film of the David Tennant Hamlet. Yet the loose trilogy of Macbeth, Hamlet and Doran’s 2012 Julius Caesar, while inaugurating a revival of filmed productions of classical texts in that style (and Wyver’s list, I think, is conservative, missing out the influence of these productions on, for instance, Rupert Goold’s Macbeth), they also marked a culmination of this work for the RSC, and the story turns instead to live broadcasting, an ambition of Wyver’s even before Hamlet opened. This is an area which has attracted a huge amount of scholarly attention, including on this blog, but the particular value Wyver brings here is a detailed insight into how the high technical standards are achieved through the placement of microphones and cameras, and he draws attention to particular moments in Doran’s 2012 Richard II which illustrate the potential of the hybrid stage-screen language, showing the fine-grained attention to analysis that is a strength of the book when it allows itself to indulge in a longer case study.

The state of play in 2019 is of a diverse and rich series of engagements between the RSC and screen media, with 2016 alone yielding the extensive regional programming around the touring Midsummer Night’s Dream, several live broadcasts, and the Shakespeare Live! event on the BBC. Yet what this book demonstrates is the continuity of this engagement across the RSC’s history. There are several lingering questions to be answered – why hasn’t the Volpone recorded in the Swan in 2015 yet been released being one of the most enticing – but Wyver’s book sets out the historical and contextual framework – along with a helpful overview of what material is actually out there, and where to find it – to allow scholars and enthusiasts to continue the work of piecing together this history. It’s a huge achievement of patient archival research and practical industry knowledge, which will become a standard reference work for those of us toiling in this area.

Thank you for the review. In 63/64 the BBC broadcast the Clifford Williams production of The Comedy of Errors. I made an audio recording of it but heavens knows where it is and what state it is in! Does anyone know if a full video recording of this production exists?

It’s online Ray! This resource is great. http://shakespeare.ch.bbc.co.uk/ However, you need to be attached to an educational institution to view it.

Thank you, Peter – this is enormously kind and generous, and it is of course thrilling to see the book receive such a careful and thoughtful response. I am delighted.

Many thanks Peter. Short of starting a PhD I shall have to figure out another way of getting to see it again.