June 10, 2019, by Peter Kirwan

Henry V, or Harry England @ Shakespeare’s Globe

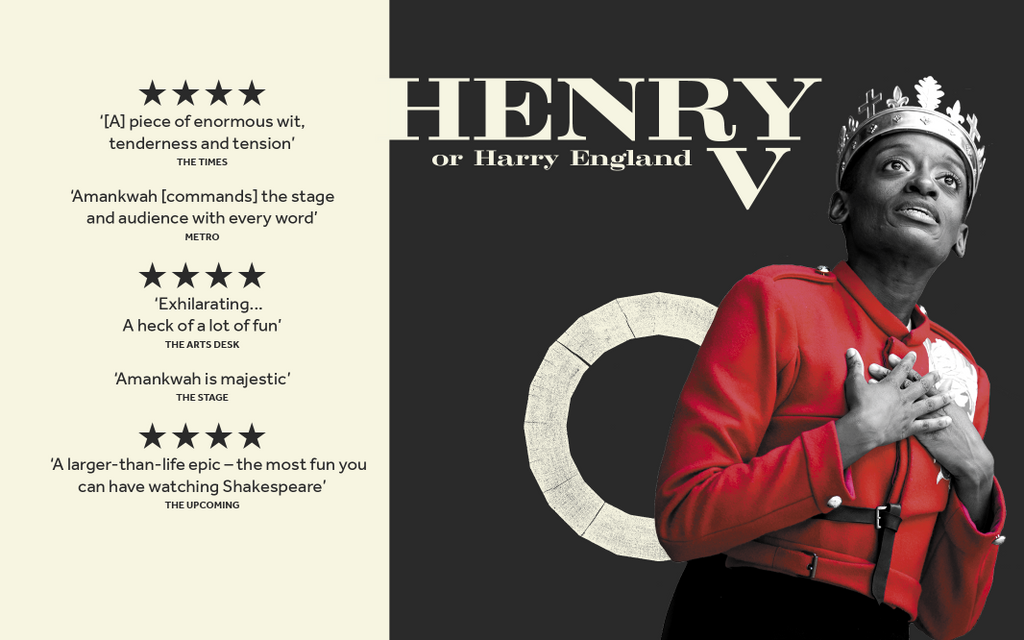

When I saw Sarah Amankwah in Doctor Faustus at the Sam Wanamaker just before Christmas, I expressed a hope that she’d be a regular at the Globe. The fact that, with very little Shakespeare experience behind her, she has then taken the major through-line role of the Henries trilogy as Hal/Henry V, suggests I wasn’t the only one struck by her performance. Having excelled as a complex, confident Hal throughout the first two parts of the trilogy, Amankwah shifted into an even higher gear for Henry V.

Gone were the county/regional flags of the Henry IV plays, all replaced with the three lions of Henry V. The tiring house was now boarded up, Jessica Worrall’s set giving Henry V a cleaner, more organised look. Amankwah’s Henry was at ease in his throne of power, still inscrutable and effortlessly imposing, with his nobles decked out in red livery. The opening scene (following a communally delivered chorus, and with 1.1 cut), saw Henry in quiet dominance after the unsettledness of the previous two plays. But the amused, disbelieving laugh Amankwah gave as Henry picked up one of the tennis balls from the magnificent casket delivered by the Dauphin showed that this wouldn’t last.

At the siege of Harfleur, squibs gave off flashes and explosions as the panels of the tiring house were knocked through and the English armies emerged through a wall now festooned with French flags. The scene gave Amankwah the first of her grandstanding battle speeches, and for the first time in a long history of watching this play, I heard the speeches clearly and powerfully. Amankwah’s presentation of Hal had imagined the Prince as able entirely to fit himself to the moment, and on the battlefield Henry was a born leader, a clear voice ringing out across the auditorium and urging the English to victory. Later, for the Agincourt speech, there were no pyrotechnics, just a clear, persuasive, deliberate delivery, taking time to single out the individual nobles mentioned, but also encompassing the gathered audience. When Henry spoke, he instilled confidence; he made sense; he offered clarity and an obvious way forward. It was no wonder that the troops fell in line.

Importantly, though, while Henry was charismatic, he was not smooth. The strength of Amankwah’s performance was its sincerity and deliberateness. When Henry showed emotion, it was all the more effective for breaking through that equilibrium. Faced with the traitors Scroop, Cambridge and Grey kneeling and offering histrionic apologies to the King they had betrayed, Henry had no time for their hypocrisy; having treated them with cool efficiency until that point, he now tore into them, his shouts shaking his whole body as he denounced their two-facedness and had them executed. Then, on ending the Siege of Harfleur, his promises that his soldiers would rape women and kill children felt terrifyingly genuine; Henry may have been ‘acting’, but if he was, it was indistinguishable from his real emotion. Amankwah, that is, was so strong an actor that Henry himself presented as a consummate performer, entirely believable as both a lover and a mass murderer.

If there was a moment of vulnerability, it was following the night-time scene in which Henry had remonstrated with his own soldiers. While debating with Nina Bowers’s Michael Williams, Henry had shown no hesitation in explaining the rightness of his king’s (his own) position, passionately yet logically setting out the case that the king had no responsibility for his subject’s souls. But left alone, Henry fell into genuine soliloquy, Amankwah capturing the long, dark night of the soul as Henry wrestled with himself, body contorting as he tried to convince himself of his own argument. It was a brilliant delivery, capturing the complexity of a King who presented himself with utter surety to his troops, but who was still conflicted behind all that.

Thankfully, despite the strength of Amankwah’s performance – which inevitably dominated this play more than any individual performance had dominated 2 Henry IV – Henry V didn’t privilege its title character at the expense of the rest of the ensemble, and the ethos of right-actor-for-right-part worked here to find surprising readings. Colin Hurley as Princess Katherine was just one of the pleasant discoveries, offering a demure, careful reading of the character shielding herself behind protocol and language to manage her own ambivalence about the wooer. The French lesson scene, with Hurley playing off Leaphia Darko’s Alice, was particularly enjoyable, the two getting grumpy with one another over the Princess’s inability to take gentle correction on her mistakes, and the two both appalled at Alice’s flat-out pronunciation of ‘gown’ as ‘cunt’. The wooing scene was persuasive; Amankwah’s Henry was not mawkish or awkward, nor overbearing in his assumption of privilege; rather, he enacted the same strategy of sincere presentation that had characterised his war speeches, just on a one-to-one level.

Where 2 Henry IV had been a little messy, here moments of bawdy humour were juxtaposed with moments of emotion to powerful effect. Jonathan Broadbent’s Mistress Quickly paused perfectly on her explanation of how she felt Falstaff’s feet and then worked her way up, rolling her eyes at the audience as they cottoned on and laughed; but at the end of her scene, she ran off the stage howling as Pistol and co went off to war. At the end of the first half, Broadbent’s Constable had been rolling his eyes at the Dauphin’s (Sophie Russell) never-ending praise of his horse; but as they left to see how many English they could kill, the Constable backed away keeping his eyes on the audience, pointing at us and beginning to count the bodies in French, a comic line but also a threat. Russell reappeared as the Boy, who joked freely with the audience, but then laid down his cap on a luggage bag and walked off to signify his death. The little grace notes throughout were continually effective.

For those who had been watching the trilogy day, there were some nice pay-offs. Seeing John Leader’s meek Bardolph finally stand up for himself and pull his sword on Nym (Helen Schlesinger) and Pistol (Hurley) felt like a victory; and Hurley got a great deal more to do as Pistol, having his swagger beaten out of him. But the expanded list of characters also yielded some fine performances, especially for Steffan Donnelly who got his best role of the trilogy as Fluellen. With the scene of the four captains cut, more focus was placed on Fluellen, played by Donnelly as an insufferable pedant who simply wouldn’t stop talking, rambling on and on to a bewilderingly patient Gower (Philip Arditti) about Alexander the Great and leeks. Donnelly’s performance was thoroughly entertaining and trod a nice line between pompous and kind, as in his insistence that Williams take a few pence from him. And after the indignities of Falstaff, Schlesinger did a surprising amount with the small role of Queen Isabelle, the real power behind Arditti’s King of France, sharing knowing looks with Henry. One suspects that a match between her and Henry would have been less one-sided.

The war scenes were a little underwhelming, with Agincourt itself being represented almost entirely by Le Fer and Pistol’s confrontation. But what this ensemble intelligently realised was that this was a play whose drama was in diplomacy as much as war. Hurley – having an extraordinary evening across all his roles – was brilliant as Montjoy, the repeated returns of the Herald even eventually getting under Henry’s skin; his final entrance, beaten and slow, spoke more than any onstage violence.

And in two musical sequences, the entire ensemble came together to create something truly unique. The closing jig brought all of the musicians as well as the cast onstage carrying drums, offering a loud and rousing percussive rhythm to close off the trilogy day. But more powerful and more specific was Non Nobis. Accompanied by the BSL interpreter (doing a fantastic job translating both Latin and French as well as early modern English), the ensemble knelt and sang Tayo Akinbode’s setting, which drew on American Roots melodies that evoked anything from deep South spiritual to the second lines of New Orleans jazz funerals, with Sarah Homer’s sax, Richard Henry’s trombone and Adrian Woodward’s trumpet offering a woozy melody while King Henry wailed a descant. The music was spellbinding, and allowed Amankwah to lead her troops in something deeply emotional and personal, Henry’s lament sounding for both the English and the French.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply