June 17, 2018, by Peter Kirwan

Ellen Terry’s Very ‘Merry Wives of Windsor’ @ Queen’s University Belfast

The most delightful part of academic conferences is always* the moment when academics get up to put on their own play. Liz Schafer’s contribution to the (now annual) British Shakespeare Association conference was her adaptation of Ellen Terry’s three-scene cut of The Merry Wives of Windsor. Terry’s playlet was a self-created vehicle for her own star turn as Mistress Page, which played in Brighton and London in 1918 to audiences still experiencing the traumas of war.

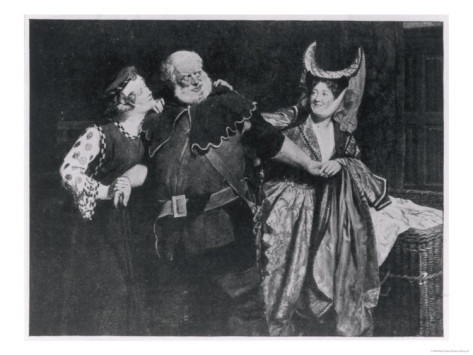

The performance centred around David Findlay’s scenery-chewing (if there were scenery to chew) turn as Falstaff, first seen ordering Robert Shaughnessy’s delightfully hapless Robin to deliver letters to Mistresses Ford and Page (a task which fittingly stretched Robin’s capabilities). The scene then passed to Alison Findlay’s Mistress Page, squeezing every laugh out of Falstaff’s bombast, before turning in shock to a somewhat-thrilled Mistress Ford (Deanna Rankin), who teased Mistress Page with her secret before they exchanged letters and collectively gasped.

All this was preliminary to the buck basket scene. Falstaff swaggered back on stage and boomed out his love for Mistress Ford, before running to hide on the approach of Mistress Page – and, in a lovely bit of site-specific staging with presumably unintentional ramifications, attempted to hide himself behind QUB’s display boards for an oral history project on Belfast’s peace walls; the boards formed a passable stand-in for an early modern tiring house, with a central gap that Falstaff desperately tried to squeeze himself through. Unable to fully conceal himself behind the peace wall, Falstaff eventually revealed himself after a beautifully realised dialogue between the women aimed at terrifying him. The buck basket was tiny, and as the playlet descended into farce, the attendants (Schafer and Daniel Yabut) shoved the basket on his head, draped the lining around him, and bundled him out through the audience, bowling over spectators on the way.

It was a lovely pre-panel treat, performed with good humour and reckless abandon, but also offered a pleasing insight into the kind of extraordinary cut performed by star actors a century ago. Terry’s piece was not a one-woman piece, and actually gives the actor playing Mistress Page a central role as part of an ensemble, depending on snappy repartee and a deflation of other egos. Hearing a ten-minute chunk of Merry Wives worked well in that play’s favour, finding some lovely wordplay and rhyme in the language, and culminating in a great piece of physical comedy. Sometimes, slightness is enough!

*not always

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply