April 28, 2018, by Peter Kirwan

Macbeth @ The National Theatre

‘Now, after a civil war’ declared the programme, presaging the latest in a long line of not-quite-now post-apocalyptic settings for a major Shakespearean production. In Rufus Norris’s hands, the concept was at its laziest; not here the specificity of a post-Brexit decline as in Melly Still’s Cymbeline at the RSC. In this Macbeth, Scotland (dominated by Rae Smith’s steep, angular catwalk stretching from stage level to a cavern in the back wall) was barely a state; people gathered for safety in small groups, and ramshackle paramilitaries banded together in loose allegiance under a ‘King’ marked by his matching red suit, as opposed to the found, recycled outfits of the rest. The setting said everything and nothing, offering a generic there-but-for-the without daring to commit to an actual critique of what underpinned this fallen state.

To this end, the setting offered an aesthetic rather than a cohesive interpretation. The closest the production came to specificity was, surprisingly, in the presentation of Banquo’s murderers; here, two stereotypes of working-class indolence; Alanna Ramsey in fishnets, leather jacket and peroxide top-knot, and Joshua Lacey in denim. In a world where everyone who had survived seemed to be a trained killer, Macbeth deliberately targeted amateurs to assassinate his old friend, playing on the twosome’s desire to get rich quick. Thrilled to be offered a cheap beer, the murderers proceeded to botch the job badly, with Lacey left dead on the stage near Banquo. The idea of a state machine that preyed on its most suggestible members to offload the wet work had real potential, but this wasn’t followed up elsewhere.

Instead, everyone lived in a reclaimed poverty that rendered all attempts to climb fundamentally fruitless from an external perspective. The tiniest differences in status – a red suit rather than a cobbled together ensemble; a chair protected by shrink wrap; a battered sofa to sleep on rather than a table – became the stakes for which people sought to rise. In a society of scarcity, with every win zero-sum, the scraps for which people fought became important. Again, the potential was there but the production did frustratingly little to develop this. The late appearance of a uniformed English military – suggesting that, if England had indeed been damaged by the wars, they had at least survived as a more cohesive nation – might even have implied a reading of the play in the light of Western intervention in tottered states (a la David Greig’s Dunsinane), but any intention here was oblique at best.

Nonetheless, the setting was coherent and the fighting for inches in a broken political and fiscal economy managed to create a world in which the stakes for everyone as survivors were clear; except the performances were surprisingly relaxed. The community that assembled around Duncan (Stephen Boxer) traded in the same dull stereotypes of performative masculinity that characterise every production along these lines (banging weapons to make ritual noise? Check. Blokey cheering? Check.). Duncan’s arrival at Macbeth’s compound (a couple of small bombed out rooms, with an open area outside) initiated a rave where Lady Macbeth pogoed to distract her intended victim and others danced on tables. Boxer’s Duncan presented as laid back, even careless of his status; a local gang leader as easily disposable as anyone else. Dwarfed by the expanse of the Olivier stage, the production felt small.

Small-scale doesn’t mean that the stakes can’t be high, of course, but there was a lethargy in the cumulative effect of the performances that (I confess) left me struggilng to stay awake. For a play that is so snappy and full of incident, no-one seemed to care very much. The exception, perhaps, was Rory Kinnear’s Macbeth, who, in his spotlit soliloquies, seemed to find a greater significance in what he was trying to achieve, especially emphasised in a lovely image of him standing stock still in the middle of the rave. Next to his rough-and-ready companions, this was a humourless and reflective Macbeth who had ideas not merely above his station, but above what his world could offer. Donning Duncan’s red suit when ‘crowned’, Macbeth sought out the witches to try and find further meaning – an idea of legacy reflected back at him in the creepy back-of-head masks worn by a procession of anonymous figures carrying the withered branches of Birnam Wood. But legacy and profundity were both fleeting; Lady Macbeth died in the same dilapidated little prefab she had first appeared in, her blood spattered on the wall from her final slashing of her chest.

Perhaps this was the production’s issue – that when the characters of the play have precious little to fight for, there isn’t a lot of excitement or energy to communicate. Horror piled upon horror – a murderer emerged with Lady Macduff’s babies smothered in plastic shopping bags; Patrick O’Kane’s Macduff sawed Macbeth’s head off onstage (in an appallingly blocked sequence that must have worked somewhere in the auditorium, but not with our sightlines); Kevin Harvey’s Banquo staggered about the stage with a bleeding head – but no-one seemed to care very much. Kinnear worked valiantly, his speeches full of portent and his customary sensitivity to emotional weight leading to some beautiful line readings (‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’ poured out in a frustrated torrent), but by the time the Porter (Trevor Fox) was using masking tape to strap his armour back on, even he seemed to have given up. As he cradled the dead Lady Macbeth, noting that life was but a poor player, he sounded as resigned to meaninglessness as everyone else.

The Olivier is a notoriously difficult stage to fill, and the choice to have one-on-one battles rather than a crowd of soldiers in Act 5 left the stage feeling particularly quiet during the final movement. The stage was dominated by the steep ramp – which allowed for some quietly stunning stage images, especially during the witches’ later predictions – and by the wasted trees that towered above the stage. These trees were bendy poles that actors frequently shimmied up to spy ahead, and the shrivelled branches at the top shook like wraiths, as if the witches were constantly watching. In the final battle they literally were – while the witches made little impact throughout the production, the sight of them atop the trees, looking down and shrieking, was at times chilling; and the closing action – in which they slid at breakneck speed down the trunks before walking off into darkness – was quite thrilling. Elsewhere, the witches were characterised primarily by turning the reverb on their microphones up to 11, and one of them running around while giving Moaning Myrtle-esque squeals. The least coherent part of the production, they still managed to at least look cool in the end.

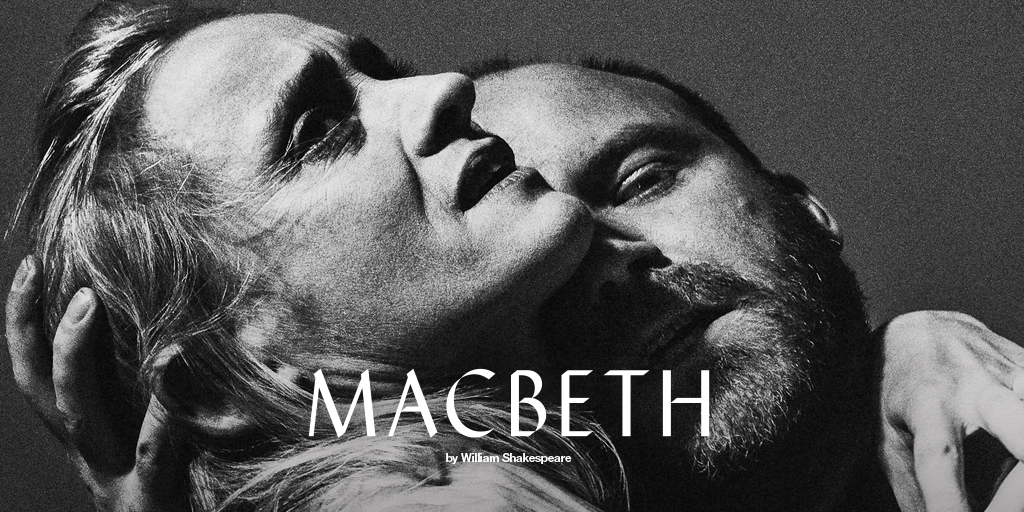

Elsewhere, the performances were largely fine if unremarkable. Anne-Marie Duff was a solid Lady Macbeth: a tower of strength to her husband in the first act, she began her hand-washing immediately after the banquet, and a brief visual sequence before the sleepwalking scene revealed that she had been unpacking the plastic bags containing Lady Macduff’s dead babies, a cheap move to try and create a short-cut to character. Duff, a little like Kinnear, seemed to be ill-served by a production that didn’t give her a great deal of time to develop a through-line – the nadir probably came as she returned to the party after chivvying Macbeth and started pogoing with Duncan. While this was a fantastic representation of her chameleon-like ability to play the host, the production seemed less sure of who she was when she wasn’t playing a role, and her death felt (to me, at least) disappointingly inconsequential.

O’Kane’s Macduff had his arc tightened by also being the bloodied soldier; watching his opinion of Macbeth reverse entirely across the course of the play was a pleasure, and O’Kane’s aggressive performance made him a genuine threat to the somewhat feebler Macbeth. Harvey was a wry Banquo, and his relationship with his daughter Fleance (Rakhee Sharma) was one of the production’s more moving successes; Fleance had a habit of sneaking around the stage under a cardboard box, and the two rolled together on the floor, giggling and joking. Fleance had a silent role during the war sequence, rounding up the Porter (who was also Seyton and the Third Murderer), marking the beginning of the end for Macbeth.

Ultimately, though, the production simply ended, a blackout coming before Malcolm had even invited everyone to Scone. And this, I think, was the production’s problem. It certainly didn’t deserve the devastating reviews it has had – there was nothing bad about the production – but this was a Macbeth that, like its protagonist, didn’t make a convincing case for what it was fighting for. The final appearance of Macbeth’s victims to distract him during his battle with Macduff was a lovely touch, but even they didn’t bother to hang around to see what was coming next.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply