October 12, 2017, by Peter Kirwan

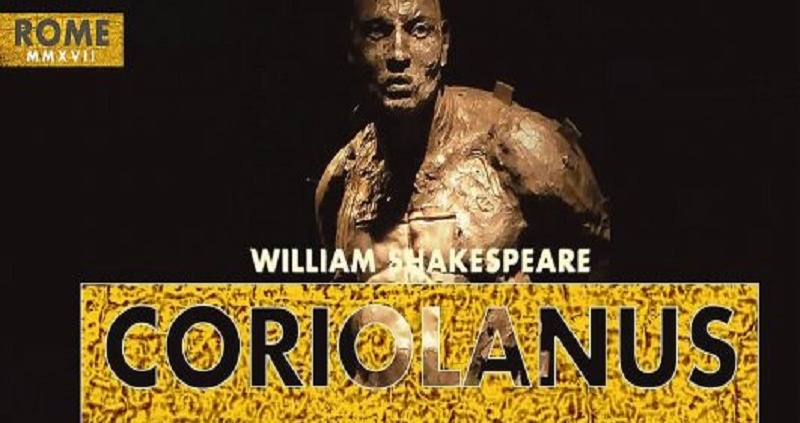

Coriolanus (RSC/Live from Stratford) @ The Royal Shakespeare Theatre/Nottingham Broadway

Much was made in the pre-show paratexts for the RSC’s live broadcast of Coriolanus of the play’s contemporaneity, and at the same time the general nature of that contemporaneity. Coriolanus, as Haydn Gwynne suggested, is a play that always feels contemporary. In fact, this was one of the least specifically resonant Coriolani(?) I’ve seen for some time. Set in a very near future, imagining warring city states who go to war with machetes and a rigidly defined class system, the dystopic world-view stripped the play of the more potently specific potential, and instead offered a version, frequently powerful, that focused on the personal rather than the political.

Not that politics wasn’t at stake here. The stratification of the class system into suited patricians and a mass of plebeians ramped up the tension of the first half, beginning with a hoody-wearing mob reminiscent of the televised scenes of the London rioters pounding on the solid door of a warehouse into which a forklift truck driver had just stashed the remaining supplies of corn. Bolstered by a large chorus of supernumeraries, the public scenes carried the constant threat of violence, yet also privileged the individual faces and voices within that chorus (and all credit here to Geoffrey Lumb and Justine Marriott for the speed and control with which they spoke on the crowd’s behalf).

Out of this large group emerged Jackie Morrison’s Sicinius and Martina Laird’s Brutus, the dressed-up tribunes who blended with the patricians but drew their power and confidence from the people. Morrison was particularly impressive as Sicinius. In flats and trousers, she at first cut an unremarkable figure, blending in at the side of the assorted nobles. But her solid confidence and clear voice asserted her presence, and as she began stirring the troops, she became increasingly animated, her voice rising to a roar, and by the time she had them calling for Martius’ blood, she was in a frenzy, laughing and shouting, drunk on her influence. Brutus was very different, a more initially confident and relaxed figure, more sarcastic and attention-grabbing in her earlier retorts to the nobles, but as Sicinius’ confidence rose, Brutus slipped more to the sidelines, and looked genuinely troubled as the mob pursued Martius to the gates led by the near-hysterical Sicinius. Laird’s voice was a great contrast to Sicinius’, but I couldn’t make head nor tail of her physical performance – perhaps flattened by the two-dimensional screen, she struck odd angles with elbows and arms, gestured without clear purpose, and most bizarrely seemed to be constantly stumbling as if off-balance; I did wonder if the point here was that she was newly elected and thus trying heels for the first time, but the lack of physical confidence didn’t align with her vocal performance.

Against the threat of the people stood a patrician class whose relative privilege was marked by the use of social wear. Sope Dirisu’s Martius himself first appeared in suit and bow tie with three glamorously dressed women; Paul Jesson’s Menenius always looked like he had come from a dinner party; Charles Aitken’s young Cominius (a real highlight of the production in an oft-overlooked role) carried himself with the air of a slightly nervy public schoolboy. The visible privilege accentuated their disdain for the lower orders, particularly in the case of Martius, whose scorn was understandably inciting. The scenes featuring the patricians were frustratingly ill-defined; it was always unclear what kinds of public space were in play or how they connected to the streets, which made the relative exclusivity of the patricians’ world difficult to interpret. This was more effectively carried out in the domestic scenes, with Katherine Toy’s Valeria in particular doing sterling work establishing the rarefied atmosphere of the upper classes visiting one another’s homes, and in these private scenes the relationship between Martius and his family came into focus.

All of this contributed to a presentation of Martius as accustomed to a world of comfort and privilege; a surprising take on the character, and one that was effective. In the battle scenes he was a strong leader, driven by action rather than words. An emblematic sequence saw him pull up an enormous warehouse door and hold it aloft for his men to run under; the silent strain and unspoken allegiance more typical of his leadership style than the more forced camaraderie; in fact, as Cominius threw beers to his soldiers following the victory, Martius already seemed more withdrawn. Back in Rome, Martius’s disdain for a politics that pandered to the masses was clear; his snipes at individual plebeians were faintly veiled, but his attitude towards the political structure brought out the real sarcasm. When standing in a white blanket on a podium in the marketplace, he performed the barest minimum to pass; snapping his hand away as soon as it was taken by each person, and at one point wiping it vigorously. The commoners left him knowing that they’d been despised, but without a form of redress; it was this universal dissatisfaction that Sicinius and Brutus whipped up.

Dirisu was magnetic as Coriolanus, particularly in sequences where the camera lingered on his face as he reacted. During the slow build-up to his ‘You common cry of curs’, Dirisu stood silently on the stage, looking at the ground, his restraint breaking on his face as the plebeians and patricians screamed and argued around him; when he finally looked up and unleashed his roar, everyone fell dead silent. His demeanour throughout (especially in the first half) balanced a barely contained fury with a stillness that emphasised the conflict of his politic restraint, and there was something almost joyful about the moment when he could finally unleash what he really felt of them (it reminded me, in fact, of Paul Scofield in A Man for All Seasons once he is finally declared guilty). He was more unfortunately dressed up as a gap year traveller when he set out to find Aufidius, and perhaps inevitably sacrificed some of his dignity, but his treatment of the brilliantly comedic servants in Aufidius’ household still allowed him to project some menace.

But he was best when partnered with James Corrigan’s Aufidius. The first half didn’t give Corrigan much chance to shine beyond his fight sequences, which were brilliantly captured; Robin Lough’s screen direction working perfectly with Angus Jackson’s thematic choices and Terry King’s fights. The clash of swords between Martius and Aufidius was one of the better stage battles I’ve seen for some time, each clashing with two swords and incorporating leaps, throwing each other against scenery and keeping up an impressive speed. But then the two men threw away their swords and grappled hand to hand. Lough cut at every blow, sometimes to only a slightly different angle, translating the percussive impact of the punches and sword clashes to the editing and offering something kinetic and cinematic. The evenness of the two set up the future conflict, even if the soldiers pulling them apart were rather less convincing in their efforts. The strength of this sequence was a great payoff to an otherwise bitterly disappointing war sequence, with short scenes separated by unnecessary blackouts and a complete lack of connection between opposing sides or an obvious spatial understanding of what was being fought for.

Corrigan’s Aufidius was something of a revelation to me. From the glimpse we got, his own society was not that different to that of the Romans, he appearing to greet the interloper in his house while wearing full tuxedo and sipping champagne. Bearded and suited, he like Coriolanus wasn’t merely a military man but a patrician. But his enjoyment of the situation was hilarious. His embrace of Coriolanus combined hug with play-fighting, and with a huge beaming smile he played up the homoeroticism for all it was worth; ‘We have been down together in my sleep, / Unbuckling helms, fisting each other’s throat, / And waked half dead with nothing’. Subtext became text, and Martius’s discomfort at Aufidius’s near-lustful enthusiasm for contact added to the hilarity but also to the uneasy undertones of their relationship.

The attempts of the Romans to counter Coriolanus’ advance were nicely played. Jesson, as Menenius, was eloquent and clear, with a quavering undercurrent of emotion that added depth to his Polonian blustering; and in a nice touch, following his own failure to influence the attacking Coriolanus, he started getting drunk with Sicinius, the two former enemies now propping one another up. Gwynne’s Volumnia led the successful assault. While Hannah Morrish did some nice work establishing Virgilia as a firm, confident woman, particularly in her refusal to be pulled into her mother-in-law’s schemes, Volumnia dominated the closing action. Coriolanus sat in a chair to hear her plea, and Gwynne played up every motion – her kneeling, her spreading of arms, her positioning of her grandson, her appeal to herself and to her city. The precision of her performance and positioning of herself, formerly a confident society lady, as vulnerable and even weak, was deeply affecting. The family portrait as Coriolanus embraced his loved ones was oddly subordinated by the camera, focusing rather on figures like Aufidius, removing some of that connection to Coriolanus at a crucial moment, but by this point he was broken and clearly anticipated his fate.

The production concluded with two powerful images. The arrival of the women back in Rome was celebrated with petals falling from the ceiling and a jubilant crowd kneeling in celebration, Cominius holding up a crown of victory for Volumnia to take. The women walked through, ignoring their celebrants, and Volumnia looked at the crown only to walk straight past, leaving Cominius looking after her in confusion. The ambivalent celebration was followed by Aufidius’ final betrayal (and, as a side note, I appreciated seeing some rarely staged scenes such as the other Roman defector from 3.3 and Aufidius’s conversation with the Volscian nobles). When Aufidius’ plan went into action, he had about six or seven men grab Coriolanus simultaneously, Coriolanus fighting and kicking them off while Aufidius got a chain around his neck. Everyone else was thrown off until Aufidius and Coriolanus were locked in a death embrace, Aufidius pulling on the chain long after Martius went limp. A processional finale was less effective than either of the two more interestingly conflicted images that came before.

The production was scrappier than I would have liked. The live music (strings) was simply awful, tonally completely inappropriate for the setting and play; the setting was uninspiring and disappointingly apolitical; and the direction of the fast scenes at the start of the play lacked energy. But the central performances shifted this to a play of personal relationships affected by larger political shifts, and on those terms the play achieved a great deal.

Thanks, as always, to Peter for an exceptionally thoughtful and deeply informed response to the broadcast, recognising the live adaptation process alongside the stage production. But – as the screen producer – let me add that the ‘brilliantly captured’ fight scenes (and I agree with the description) benefitted enormously from the collaboration of vision mixer Peter Phillips with the screen director Robin Lough. Sequences such as this are so unpredictable and unfold so fast that they rely in a fundamental way not only on the exceptional camera operators and the screen director but also on the skill, experience and fast fingers of the vision mixer – and in the world of stage broadcasts Peter Phillips has few if any peers.

Many thanks John, and what a disappointment that Peter doesn’t get a credit in the live broadcast programme handout! Great to celebrate that work; the speed and canniness of the editing in this sequence was really noticeable.