January 31, 2017, by Peter Kirwan

The Two Noble Kinsmen (RSC) @ The Swan Theatre

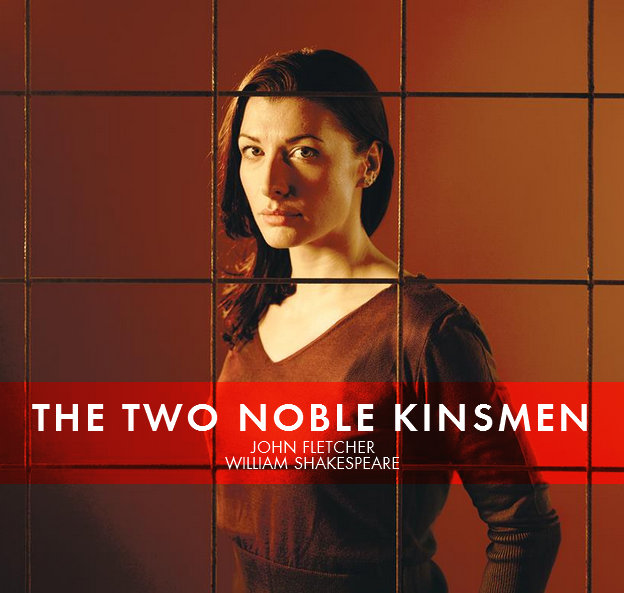

Just over a decade since I saw the RSC’s Canterbury Tales company offer a fascinating script-in-hand staging of The Two Noble Kinsmen, it was a pleasure to return to the Swan at last for a full-scale professional production, especially in the hands of Blanche McIntyre, fresh from a superb Noises Off at Nottingham Playhouse. While I’m not convinced that this is the production that will revive the play as a core part of the repertory, McIntyre’s inventive production made an important intervention by staging the play as part of a vital engagement with contemporary identity politics, demonstrating the play’s potential other than as part of a box-checking effort at ‘completeness’.

In this world, Athens and Thebes stood not just as states at war, but as competing social environments for expressions of gender and sexuality. Under Gyuri Sarossy’s Theseus and Allison McKenzie’s Hippolyta, Athens was a queer space where Theseus could kiss Chris Jack’s Pirithous publicly on the lips (albeit to Hippolyta’s disapproval, the enmity between wife and lifelong friend one of the production’s funnier and tenser threads) and Frances McNamee’s Emilia was in love with her maid (Eloise Secker). Emilia was not at liberty to express her love openly, but the production’s tenderest moments came between the two women as they exchanged a rose (while Palamon and Arcite leered on) and in their pained silences during scene transitions as Emilia was forced to promise herself to one of the men.

While Theseus privileged his public attachment to Pirithous, Athens was full of women in authority roles, and the two men were vastly outnumbered, most comically in the opening scene as Theseus found himself confronted by seven women ostensibly kneeling to him but at the same time placing him under extraordinary pressure to commit himself to conflict. It was perhaps no surprise, then, that he was visibly invigorated by the culture of Thebes, epitomised by Palamon (James Corrigan) and Arcite (Jamie Wilkes). These two first appeared identically dressed in vest tops and combat trousers, jogging with bricks in their backpacks, in a show of huffing masculinity. Palamon and Arcite were coded as aggressively heterosexual, their back-slapping camaraderie an expression of unity in service of the state and each other. Their chivalric code drove Theseus to shouts of laughter, he throwing himself into the spirit of their conflict and aiming to outdo them in masculine spectacle with the establishment of the tournament and pyramid, to the increasing dissatisfaction of his wife and court.

The attitudes of the two societies needed to be foregrounded much more prominently to really drive home the central conflict – that fundamentally, Palamon and Arcite were fighting to the death over a woman who, not only had no idea that she was the object of their affections, but who was quietly and sadly in love with another woman. This aspect, too, needed much more attention, and I couldn’t see any reason not to explore this further through non-textual moments, especially given Secker’s beautifully expressive, resigned performance as the maid utterly disempowered from acting on her own feelings. But it set up an excellent set of stakes realised in McNamee’s expressions of disgust and disbelief at what was asked of her. Her outraged cries of ‘yes’ mixed sarcasm and horror as everyone – Theseus, Palamon, Arcite – refused to ask her what she thought of the plan to marry her off.

Corrigan and Wilkes were excellent as the two feuding friends, with only a deeply awkward and overlong fight sequence showing some strain. The two came into their own when in prison, realised in Anna Fleischle’s set as two wire grids reaching to the ceiling, which kept Arcite and Palamon suspended over the audience at the side of the thrust and separated by the gulf of the thrust. The bonding language of the two was disrupted poignantly by the tender scene between Emilia and her maid, and the two men were entirely oblivious to the actions of the women, instead leering lustfully at Emilia. Once she left, they turned into schoolboys, brilliantly capturing the childishness of the ‘I saw her first’ debate, and rattling the cages at one another. The same cages were lowered again later for their fight which, although not choreographed very smoothly (especially when the two were broken up by Hippolyta, which seemed to be bungled), allowed for some effective moments as the two smashed themselves into the grid mere inches from the noses of the audience in the front row.

The long central sequence of Arcite looking after the escaped Palamon was played for laughs a lot of the time, particularly as Palamon had his arms manacled behind his head and had limited movement, thus making his attempts to attack Arcite comically futile. Yet a sequence where Arcite fled up the grating and Palamon was left kicking the bottom of the grille impotently for some time also managed to capture something of the pathos of their thwarted friendship, both men raging helplessly against a set of circumstances that they felt left them with no control. As the play switched tacks to the tournament, and the two were paired up with accompanying soldiers (introduced via video game style ‘Player Select’ introductions), the central relationship was inevitably displaced in focus.

I privilege in this review the central relationship and the potential it had for coherence, because this was in other respects a sometimes ramshackle production. The aesthetic was a kind of classical fetish chic, with characters wearing single bits of armour over jeans, plenty of leather and a lot of exposed flesh and tattoos. Emilia’s costume changes were perhaps most striking, sometimes a classical hunter with bow and arrow, sometimes a lady of the court with backless dress revealing huge angel wing tattoos, and latterly a bride in white dress with plumped-up sleeves. While there was a broad shift of style between the informal court presided over by a laughing Theseus and the more ceremonial version ahead of the tournament, where the nobles donned full dress, there were few obvious structure underpinnings to the choices, which also contrasted with an austere set full of concrete ramps and breeze blocks.

The Jailer’s Daughter (Danusia Samal), contrasting with the fetish gear, was prim from her first appearance in cardigan, blue skirt and an attitude of childish enthusiasm. The obvious openings on the costume signposted a mile away that her madness would, as customarily at the RSC, be rendered through her gradually losing her clothes, which duly happened over the course of several monologues that Samal handled well but without a great deal of tonal variety. The madness slowly took over and she became distracted, but there was quite a leap from this to her appearance with the villagers, led by Sally Bankes’s crop-carrying, feather-hatted ‘Schoolmistress’, a lady of the manor who managed her unruly troupe of performers uncompromisingly. The Morris was entertaining, capped off by two men riding enormous phalluses like horses, while the villagers panted to climax and then gently tossed handkerchiefs into the air.

As the play moved towards its climax, the obvious difficulties for a modern audience took over. The play demands a great deal of work be done by actors describing, and I found the reports of the tournament somewhat uninspiring. The prayers, however, worked extremely well, with some lovely spectacle in a flying dove, a tree emerging from the ground, and the gods standing stone-faced on the balconies (in a great touch, Secker doubled as Diana, doubling the semantic meanings of Secker as both the object of Emilia’s love and the goddess to whom she has devoted herself.

Yet following the battle, the production very suddenly shifted to foreground a critique of Theseus as its main point. Palamon exchanged pleasantries with Paul McEwan’s genial Jailer, who brought him a bucket and reluctantly accepted the gifts of money that Palamon asked his imprisoned companions to share. Then Palamon knelt down in front of the bucket, and the Jailer produced a sword to conduct an immediate execution. Corrigan did excellent work here mirroring his earlier prelude to the duel with Arcite, steeling himself and then repeatedly pulling away in reluctance, trying to wrap up his life’s loose ends, before a last minute reprieve. Arcite, meanwhile, was revealed punch-drunk in victory, badly bloodied and woozy, unable to fully communicate with Emilia, the first hint of the production’s disillusionment with the whole idea of the tournament. When he was subsequently carried in on a stretched following his accident, his body was unpleasantly contorted and he could do no more than splutter out his goodbyes.

As Theseus began his joyous celebration of the culmination of chivalric values and the pleasure of the gods, Palamon stood up from cradling Arcite’s body, and marched out, to Theseus’ discomfort. Palamon was followed by Hippolyta, Pirithous, Emilia and her maid, leaving Theseus onstage with only slumped attendants and Arcite’s body. While I didn’t feel the production had adequately built up, it was a powerful and embittered end to the production, foregrounding the destructive tendencies of love without consent, a valorising of violence, and the losses accrued in pursuing ideology without attention to human cost.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply