September 7, 2016, by Peter Kirwan

Black (dir. Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah) @ Broadway Cinema

Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah’s Black is painful and upsetting. It’s hardly the first film to reimagine Romeo and Juliet as an urban gang war, a setting that reappears from West Side Story to Romeo and Juliet in Harlem, and canonised as a reading by Baz Luhrmann’s inescapable film (quoted visually here in a very different fish tank shot). But Black takes several steps further away from Shakespeare; as a closing caption notes, the film’s real purpose is to highlight the number of deaths (23) in gang wars in Brussels in recent years. Romeo and Juliet is here, but stripped of the safe distancing that Shakespeare’s text and plot offer. The question the directors ask is what it might mean, among the tightly wound migrant communities of contemporary Brussels, to step outside one’s approved social group.

Marwan (Aboubakr Bensaihi) is a member of the 1080s, a street gang of petty thieves of mostly Moroccan descent, although one strand of the film’s discourse around identity is Marwan’s insistence that he is Flemish and his older brother’s retort that he will always be an outsider. The film opens with a dramatic smash and grab by Marwan followed by a chase through Brussels’ streets, and Marwan’s brother Nassim (Soufiane Chilah) takes the fall following a hilariously extravagant shopping spree using stolen credit cards. With the violent, impulsive older brother in prison, Marwan finds himself chatting to a young black woman who has also been picked up by the police.

Marie-Evelyne (Martha Canga Antonio) – or Mavela, as she insists Marwan calls her – is attached to the more brutal Black Bronx, a francophone group of young black men and women. Their leader, X (the terrifying Emmanuel Tahon), organises more serious activity for the enigmatic Mr Dominique, from selling drugs to extorting protection money from the musician Koffi Kemba. An early scene makes clear the danger that Mavela is in; while she is considered initially exempt from the group’s usual ‘rules’ owing to her brother’s membership, it is slowly revealed that the women of Black Bronx are expected to sleep with all of the male members on demand, and punishments for having sex outside of the gang are hideous.

The opposed depictions of the two race-defined gangs risks stereotyping at best and flat-out racism at worst. The 1080s behave appallingly to their girlfriends, swapping them as a bargain between brothers without consulting the women, and Marwan’s attitude towards his nominal girlfriend, the Italian Sindi (Marine Scandiuzzi), is one of total disinterest. But the Black Bronx are serial gang rapers, both within the gang as a standard perk and of outsiders as a punishment. In one horrific scene, Mavela is forced to trick Nassim’s girlfriend Loubna (Sanaa Bourrasse) back to X’s den, and as the men surround Loubna they pant, laugh, bare their teeth, before jumping on her as a group. There’s a longstanding tradition of performing the Capulets as more aggressive than the Montagues, but with the communities here divided along racial lines, I found the film risked dehumanising its black men. Given that the directors proclaim their own Moroccan roots on the film’s website, and that the film’s very title is Black, I’d have hoped that they would have taken more pains to avoid what comes across as prejudiced essentialism.

The film works hard to establish a believable set of contemporary stakes onto which to transpose Romeo and Juliet. The slow build-up of the romance between Mavela and Marwan is done with a refreshing lack of saccharine; on one of their first dates they compare burping over fast food, and their meetings are often by chance (perhaps too often to be believable). Silent scenes see them hanging out and dancing on a station platform, they drift into a relationship after swapping numbers, and Marwan doesn’t even break it off with Sindi (officially, at least). The romance shifts up a gear when Marwan somewhat improbably stumbles across a beautiful old church under renovation, where he sets up a hideaway for Mavela and himself. The constant sound of the sirens outside permeating the church walls, of course, ensures that the viewer can never treat this space as entirely safe. The issues they face are to do with neither their family nor their race (in fact, race becomes a joke for them, as Mavela teases Marwan when she catches him looking at her by asking if she should be wearing a burqa; he responds ‘we’re all Africans’), and they walk the streets together freely; they simply know that they need to be left in peace. There is never any talk of marriage, although the candlelit sex scene in the Catholic church suggests at least a cinematic sanctification of their relationship.

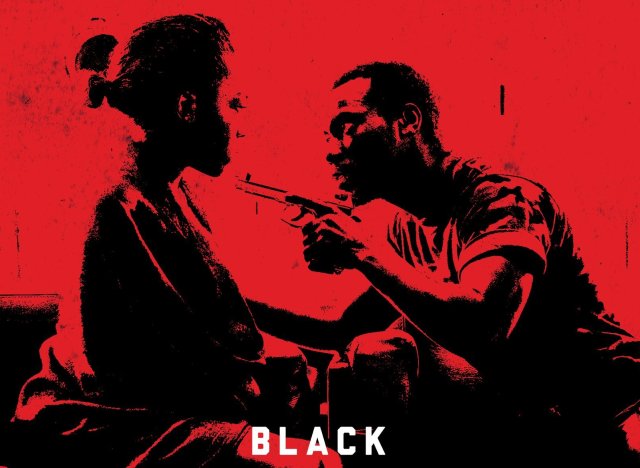

For a low budget film, it is beautifully shot. Hand-held cameras capture the opening street chase as a gritty, breathless action sequence; a tense scene where Marwan accelerates his car to dangerous speeds to get Mavela to open up to him uses low angles to exaggerate the speed of the car and imply the danger both are in; slow motion sequences of lone individuals walking through empty areas then introduce blurred background shapes that come slowly into focus as attackers close in. Brussels is a fabulously varied background: streets and construction sites, tunnels and open squares, nightclubs and squats, alleyways and apartment buildings add texture to the gangs’ interactions, and the ability to navigate the city effectively becomes part of what makes individuals successful. A moment of genuine shock occurs when X pulls out a gun to kneecap a rival gang member who is standing on his turf; the incongruity of the cobbled street and pavement café with the extreme violence (see also: In Bruges) makes a powerful statement about X’s audacity.

The 1080s and Black Bronx do not have a particular feud, but are driven by random acts of pettiness and bad luck. The gangs first meet when Jonathan (Simon Frey), a white 1080, pesters the pregnant Doris (Ashley Ntangu) on a train, and she calls her Black Bronx boyfriend Alonzo (Brandon Masudi) over to intervene, leading to a station brawl with sickening violence – the gangs know how to creatively hurt enemies in the short time before police arrive, and fingers are burned, limbs cracked against the edges of steps, and stomachs pummelled, all in close-up. The film does a fine job of following through the small individual tragedies that make up the wider miasma surrounding the gangs; although Alonzo will go to war over Doris, he is next seen bringing home another woman to fuck in front of her. Later, even though she is ejected from the gang, she tells Mavela that women cannot choose to leave the Black Bronx, creating a persuasive set of correspondences for Juliet’s inability to leave her family. The attack on Loubna is another chance happening, while it is Sindi’s sudden feeling of abandonment by a boyfriend she doesn’t seem hitherto to have cared about that leads her to follow and photograph Mavela and Marwan before taking the pictures to X and the Black Bronx.

Inevitably, it is Mavela who is punished. It isn’t made clear why the Black Bronx don’t pursue Marwan, and the film has to take some bizarre and unexplained leaps to re-establish the conflict between the two gangs towards the film’s end, but the film is far more interested in Mavela’s arc, which is one of rape. The shots of shadows running through the church towards Mavela, not long after Marwan has stepped out to get food (and is coincidentally picked up by the police for no reason; the police in Brussels are apparently much more interested in helping screenwriters get out of narrative dead ends than in solving crime), is beautiful and ominous, but then the gang rape is played out in excruciating detail, each member taking turns. Much of the rape is shot from close-to-POV of both victim and victimer(s), lingering on Mavela’s body. While the film is effective at capturing her ordeal, and perhaps should be praised for not flinching away from the horrors, it is also complicit in finding as many ways as possible to aesthetically frame her convulsing, naked body.

Mavela’s arc thus becomes one of a victim of abuse hardened by her ordeal – my first thought for comparison was the Game of Thrones Sansa Stark storyline, but Women Beware Women might be more relevant to readers of this blog. A stunning montage set to ‘Back to Black’ sees Mavela join the gang full-time, drinking, taking drugs, kissing another female gang member in a nightclub, robbing an off-licence at gunpoint. She is doing this partly to protect her mother (one of the film’s most upsetting scenes shows her being forced to move out of her mother’s house to live with the gang full time, to her mother’s uncomprehending distress), but Antonio’s phenomenal performance catches a dead-eyed resignation that resistance is futile. I can’t overstate here how good the unknown cast (largely picked off the streets) are – for all the film’s flaws, the sense of threat and unpredictable violence is palpable, and this is the first take on Romeo and Juliet where I have felt fear for the leads.

All around the gang activities, the adult world simply fails to protect anyone. The two police officers are both sympathetic, but impotent. Sanaa Alaoui is a patrol officer who is constantly on Marwan and Nassim’s case and banters with them while watching for infractions; it is she who picks up Marwan in fateful time for the Black Bronx to kidnap Mavela from the church, and the film punishes her by having her cradle Marwan’s body in the final shot. The male agent who Mavela finally contacts for help is keen to intervene, but he too lets her down by sending her back into the Black Bronx’s den and waiting in order to make a mass arrest; predictably, the heavily armed police response team arrive too late. Parental figures are mostly absent; Mavela’s mother is the most fleshed-out, showing genuine concern for her daughter, but she is largely off-screen rehearsing for a local production of Romeo and Juliet as a way to improve her Dutch and integrate more with the community, and by the time she really comprehends what is happening to her daughter, she can only watch her leave.

Having become sidetracked by Mavela’s victim arc, the film has to contort itself for the finale. X is suddenly picked up, raped, stripped and dumped naked and shaking on his own patch by the rival gang he had earlier faced down, provoking him into a wild rage; Nassim is released from prison and somehow finds out about Mavela, causing him to threaten to throw Marwan off a rooftop. Nassim and X force Mavela and Marwan into agreeing a meeting that becomes a pretext for both gangs to attack one another. The precise logic is sacrificed here in favour of the opportunity to frame Marwan walking into a trap alone before the brawl begins; and then the powerful image of Mavela throwing herself in the way of X’s bullet so that she and Marwan are shot with the same bullet. There is no West Side Story moment of realisation here; as the police arrive to end the battle, it is only the two officers who failed to act earlier who even notice the dead couple at the centre of a heart-shaped arrangement of prostrate arrested fighters. But the plot convolutions are perhaps forgivable here in service of the film’s broader point, as the bodies give way to the textual coda reminding audiences of Brussels’ unnamed dead.

I’m conflicted about Black. It is timely and incisive, tackling the issues of youth violence and urban identity head-on; yet its own racial politics are worryingly lopsided. It’s a beautifully shot and scored film, with composition and editing working hard to elevate and iconicise the performances of the amateur actors; yet the film’s framing of its naked victims and frenzied victimisers borders for me on an overly artful approach that neglects its characters’ humanity. However, the film’s main achievement as an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet is its well-judged transferral of the play’s stakes to a contemporary setting. This is a dangerous love.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply