July 20, 2016, by Peter Kirwan

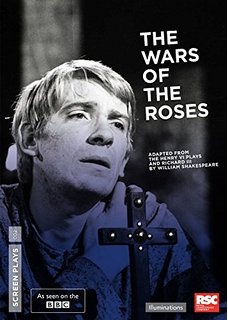

The Wars of the Roses (RSC/Illuminations) on DVD

The Wars of the Roses is one of those iconic productions – like Peter Brook’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream – that I never expected to get a chance to watch in full. Peter Hall and John Barton’s three-part condensation of the first tetralogy of history plays was one of the resounding triumphs of the young Royal Shakespeare Company. I didn’t realise it had been filmed for television until I received this, the second in Illuminations’ series of ‘Screen Plays’, following An Age of Kings. This lavish pack offers a crisp transfer of the originally broadcast trilogy, preserving some legendary performances and bringing them to a new generation of viewers.

The plays are adapted fantastically for television. The original production’s bulky but suggestive sets are re-used for broadcast, but the television direction relies on tight camerawork to create a sense of scale; while much of the blocking is theatrical, the dynamic camerawork (lots of cross-cutting and close-up, in particular) suggests a broader availability of space, so that when the camera falls back to mid-distance shots it seems to have captured only a moment of the characters’ transition across the landscape. Regular fades to black between scenes break up the ‘theatrical’ feel and suggest the passage of time. The only scenes that really suffer are those set outside, where the oppressive darkness of the theatre rather abstracts the occurrences.

There are limitations, of course. When characters appear, they emerge suddenly from a space that was clearly only feet away, shortening the off-camera space. The films are all over-reliant on close-up, which sacrifices a certain amount of dynamism – Ian Holm, as Richard of Gloucester, might as well be doing a Talking Heads in some of his direct addresses. But every now and again the constraints are used to create wonderful framing effects, such as viewing Elizabeth and Anne partly through each other’s veils when parting at the Tower, or superimposing the abstracted figure of the Father who killed his son into an upper part of a screen otherwise dominated by the face of David Warner’s pious, strained Henry VI.

Throughout, in fact, the technology that creates a dynamic television experience seems to be far ahead of its game. These aren’t technically flashy, but they are consistently aware of the medium, and the actors seem to be attuned to their environment and to the nuances made possible by the camera. The soliloquies, in particular, encourage complicity between viewer and character, actors at times almost whispering into the camera as it zooms in close to their faces. It creates one of the most intimate readings of the history plays I recall seeing, without resorting to the excesses of The Hollow Crown’s introspective voiceovers.

The productions are partly famous for John Barton’s creation of ‘new’ verse to streamline and clarify action, and indeed these history plays feel like a connected set. The new text is far from reductive, however, and I confess that it’s not easy (writing a review at the end of nine hours) to remember jarring examples of interpolated text. One fantastic joke I did notice was the interpolation of the Latin motto for ‘No woman shall inherit in Salic land’, spoken by two of the Frenchmen as Joan la Pucelle challenges the Dauphin to a duel; a sophisticated wink to those who know Henry V. It seemed to me that the role of Warwick was somewhat beefed up to make the most of his arc across the three plays, and Ian Holm’s Richard was introduced with more ominous suggestions of his ambition than 2 Henry VI allows for.

One of the complaints I have to make concerns the presentation of the set. Most seriously, the package does not include a dramatis personae, just a list of the actors involved in each production. Even this is wrong – Janet Suzman is missing from the printed cast list for Henry VI, despite playing Joan. But given the likely audience for these discs, it seems utterly bizarre that an extra page couldn’t have been devoted to showing which parts each actor plays. In the package’s defence, the essay in the leaflet detailing the circumstances of production and some of the key moments of the trilogy is excellent.

This was a classic RSC sixties cast at the top of their game, and the role-call is truly impressive. Even though it’s unfair to single the actors who have become the stuff of theatrical legend, there is still something thrilling about seeing Peggy Ashcroft in full, lisping throttle as an angry and believably aging Queen Margaret. When she emerges to offer her curses, her eyes can barely meet the camera, suggestive of her growing insanity as she meets the viewer’s gaze and then immediately darts to the sides. The performances are great across the board, although the nobles of the York/Lancaster wars are a little interchangeable in their mustachio-twirling machinations. Given the blanket avoidance of the Jack Cade sequence by so many recent productions, too, it is pleasing to see it in its rightful place here, launching the middle play and bringing what sounds like the whole of London into play.

The tone is, at times, a little monotonous, and I suspect that enjoyment of the set will depend largely on the individual viewer’s priorities. There is something here for most tastes, however. For those interested in individual characterisation and craft, the close-ups give an extraordinary range of insights. Susan Engel as Queen Elizabeth is a revelation as she parries Richard’s attempts to woo her daughter by proxy, her make-up running and every spasm of her cheek telling a story of repressed rage and helplessness combined with pride and strength. Warner’s work as Henry makes him absolutely central to the plays of which he can so easily become a peripheral character, and his haunted musings on his right to rule are, at times, heart-breaking.

For those more interested in the history plays as spectacle, there is the genuinely terrifying, screeching conjuration scene featuring Margery Jourdain and Eleanor of Gloucester’s hired priests; while the various set pieces of Richard III, notably the final close quarters battle between Richard and Richmond, or the orchestration of the public which ends with Richard swinging his legs, laughing at his own triumph from the battlements, allow the camera to move back and forth to create something of the pace that doubtless characterised the plays on stage.

The only extra is a brief documentary, Making The Wars of the Roses (or The Making of The Wars of the Roses – both versions are used). It’s wonderful to see David Warner and Janet Suzman reflecting back on work from fifty-two years earlier, narrowing the years that separate us from the RSC’s beginnings. The actors freely admit that they couldn’t tell the difference between the Elizabethan lines and those concocted by Barton, and offer some sense of the national moment that they felt the plays touched upon. It’s a lovely accompaniment, and a valuable resuscitation of a landmark production.

With thanks to Illuminations for providing a review copy.

Thank you for this review. I saw the final theatrical performances of Edward IV and Richard III prior to filming. I am fairly certain that they built out over the stalls to give the camerawork a studio feel whilst still in the theatre. John Bury’s set was very fluid but you don’t really fully appreciate that on film. After the first t.v. screenings they had a run as half hour episodes. I still have a full set of theatrical programmes. Roy Dotrice (now in his 90s) was Edward IV and on film, Jack Cade, but that role was played by Clive Swift in the theatre. I have the published text, now relatively hard to get hold of.

Many thanks for this Ray. You’re absolutely right that the production was filmed in the theatre – a misreading of the notes on my part, and I’ve corrected to take that into account.