February 29, 2016, by Peter Kirwan

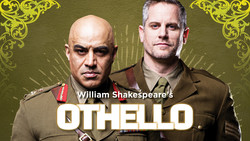

Othello (Shakespeare Theatre Company) @ Sidney Harman Hall, Washington DC

Much has been made of the casting of an actor of Pakistani descent, Faran Tahir, as a Muslim Othello in Shakespeare Theatre Company’s new production. Artistic Director Michael Kahn, in the production’s programme, suggests that this is a first for the company, and draws specifically on the fallout in the Middle East following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. It’s an interesting and potentially timely premise; disappointingly, however, Ron Daniels’s production sidestepped any specific historical or cultural exploration. What was left was a fairly rote Othello, with a beautiful set but deeply mixed performances.

The production’s weak link, unfortunately, was Tahir. At times, particularly in the second half, his natural dignity and poise allowed him to be a figure of substance, particularly (in the one of the few overt references to his religion) he prayed in a spotlight before rising slowly and approaching the bed on which Desdemona slept. But for the most part his performance was severely limited. He acted almost entirely with his right hand, his other limbs all fixed in place (except for when his other arm joined in to make a particularly emphatic point). Although his voice was at times powerful, the awkwardness of his movements and the limited range of expression rendered his performance inert. When he arrived on stage he assumed a fixed position that diminished any sense of control; he only moved on cue, rather than commanding the space, and given his small stature next to Iago, he never managed to capture the sense that he was (or felt he was) in control of his environment.

Tahir’s weaknesses were exaggerated by very weak physical direction and fight choreography. With the exception of the duel between Cassio and Roderigo, which had some pace to it, the moments of violence were poorly timed and executed, especially the Montano-Cassio fight and Othello slapping Desdemona. Most abysmal, though, was the death of Desdemona herself. Tahir looked impressive stripped down to his trousers and lying across Desdemona, but the stiltedness of his body made it look like he was doing press-ups on top of her, and the smothering looked rehearsed. Further, his response to the interruptions of Emilia was a comic aside that came across as irritation while he continued suffocating his wife. I have never been in a theatre before where people around me have laughed during this scene, and I hope never to again; the bathos and awkwardness of this moment stripped the climax of all its power.

The production was still in its early days (this was press night), but the physical problems may be a sign of the production’s unreadiness. The number of fluffed lines and mis-speakings of verse was noticeable, and the choreography looked unready. The production was particularly guilty of inattention to its chorus of soldiers, who fell into the trap of all arriving simultaneously on cue, standing stock still in pre-determined positions during a scene, and then all suddenly coming to life and running off stage simultaneously on another cue, often to incomprehensible effect (why did the troops all leave once Desdemona arrived in Cyprus, only to pop back the second Othello was about to enter?). The overall sense was of an under-rehearsed production that will hopefully improve as the run continues.

A lot of time, by contrast, had clearly been spent on design. Riccardo Hernandez’s set combined five enormous upstage wall fans with hundreds of lamps, which Christopher Akerlind used to spectacular effect to create different spaces. The stage itself was a simple raised platform, surrounded by empty and rusted oil drums, suggesting a makeshift base. Light and sound worked together to guide emotional response. While I am not a fan of non-diegetic, pre-recorded scores, Fitz Patton’s ominous incidental music and Akerlind’s creative lighting states did most of the work of establishing tonal narratives, and the actors were able to depend on the production design for overall effect.

The supporting cast around Tahir had mixed success, with the strongest performer by far being Merritt Janson as Emilia. Where Desdemona’s death drew laughs, Emilia earned a reaction of audible distress following a grandstanding final scene. Throughout, she showed great versatility as a gentle but not submissive wife to Iago, an amused and kind confidante for Desdemona, and as an indignant and vicious enemy to Bianca, throwing herself with nails extended at the arrested courtesan. In the final scene, however, surrounded by dumbstruck men, she owned the stage in a way Othello never managed to, running literal circles around the bed and physically focalising everyone’s attention on the truth through gesture and strength of voice. Her death, stabbed in the back mid-flow by Iago, was a gut-punch, and she slumped to the floor, sitting up and staring sadly in death.

The other two leads were mixed. Ryman Sneed came into her own as Desdemona during the ‘willow’ scene, where Akerlind and Patton’s combined efforts allowed the scene to fade into something more transcendent, her singing voice reverberating and lingering in a sad and elegiac moment. Elsewhere her performance was less strong; her habit of hesitating for emphasis at awkward moments disrupted the verse and diminished her presence. She was quickly sidelined, running offstage after being slapped and deferring to Othello’s anger; even her brief resistance during the death scene was given little time.

Jonno Roberts as Iago was stronger, although one of the actors struggling most with textual slippages. His approach to spontaneity was interesting, often working through opportunities to present himself as speaking on his feet, and doing something similar as part of his approach to manipulating Othello. He relied on letting Othello come to his own conclusions, presenting himself as if only just thinking through his own observations, and picked up quickly on brief flaws in Othello’s defences to pursue his point. Roberts’s Iago was precise and formal, but showed a comradely intimacy with Othello in particular, including curling up with his arm around him to shield his head during his epileptic fit. The one slight frustration was the lack of differentiation between his asides and his in-world dialogue; Iago’s duplicity was, as a result, less well realised than might be expected.

While the supporting cast were largely efficient, the production’s odd spatial inconsistencies (Roderigo chased Cassio out through a different door than the latter had exited through), unusual choices (Othello did not wound Iago in the final scene) and poor physical work were all symptoms of a production that didn’t seem to have a particular purpose. Othello’s otherness was understated, the gender politics were implicit but subordinate, and the sense of what was ultimately at stake in the play’s conclusion was unclear. Perhaps the most effective moment was Iago slumping, bored, to the foot of the bed next to Emilia’s body and pointedly ignoring what was going on elsewhere. This indifference, at the moment of Othello proclaiming his own misguided legacy, implied an interesting cynicism at the play’s conclusion. Hopefully, as the run goes on, the production will determine more what it has to say about Othello today.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply