September 6, 2015, by Peter Kirwan

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Shakespeare Theatre Company) @ Sidney Harman Hall

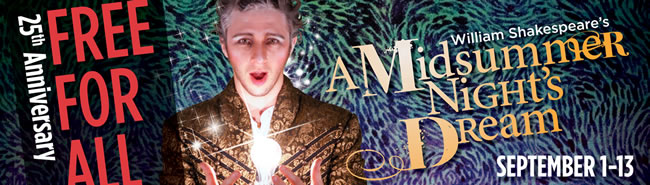

It’s been nine years since I saw the Shakespeare Theatre Company tour to the Swan in Stratford-upon-Avon with their wonderful production of Love’s Labour’s Lost, and I’m delighted to have been able to return the visit while I’m based at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC this month. I’m also fortunate that this September marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the theatre’s rather miraculous ‘Free For All’ celebration – a full-scale production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream running for two weeks with every ticket (almost a thousand at every performance) given away for free. The National’s Travelex £15 season rather pales by comparison.

Ethan McSweeny’s revival of a successful 2012 production set the play within a dilapidated theatre, beautifully realised in Lee Savage’s set. After the opening scene, a lush red curtain collapsed to one side revealing a mothballed playground of costume boxes, broken pianos and flickering chandeliers, into which Peter Quince wandered, humming ‘There’s no business like showbusiness’. Then, as the Mechanicals left, a series of trapdoors eased open to reveal a giggling group of fairies dressed in Victorian underwear who proceeded to empty out the costume boxes and begin parading. The influence of Victorian productions of Dream, from the ghosts of the proscenium arch magic spectacle to the presence of a young child as the Indian Boy, hung heavily over this production, creating a space of nostalgic play that underpinned all three plots, the detritus of the theatre becoming the shared properties of the forest.

At its most playful, the skilled acrobatics of the fairies made this a joy to watch. Led by Adam Green’s Puck, the fairies swung upside down from chandeliers, hoisted baby grand pianos into the air, peeked out of trapdoors to steal clothes from the lovers and, in a marvellously uncanny sequence, appeared dragging the aforementioned baby grand as a chariot carrying Titania and Bottom while an opera-singing fairy lashed a whip. While Dion Johnstone’s majestic Oberon and Sara Topham’s austere Titania had a more sinister aspect to their power, casting thunderbolts that lit up the theatre when angry, the supernatural was here a world of eternal playtime. Green’s wonderful Puck delighted in his mischief, his range of silly voices and his wilful enjoyment of his errors, rendering the machinations of the fairies delightful rather than threatening.

The human world, by contrast, began with a somewhat odd evocation of 1930s fascism as Theseus and Hippolyta (Johnstone and Topham again) delivered their opening lines as a public address from a balcony. The severity of this set-up wasn’t really explored further than its formal contrast to the disruptive and chaotic fairies, but the transition in tone worked well. Ralph Adriel Johnson’s Demetrius was a strait-laced college boy in full uniform, contrasted with the hipster Lysander (Stephen Stocking) whose ever-present acoustic guitar initiated a lot of humour, first through his self-indulgent songs to Hermia and Helena, and then later as an aggrieved Helena threw it down a trapdoor. Chasten Harmon’s Hermia was a tempestuous schoolgirl in short skirt, while Helena (Julia Ogilvie) wore layers of formal clothes as her far more staid friend.

The simple contrasts among the lovers allowed the forest to act as a leveller. Right from the start, as Hermia and Helena reacted with sadness to the former’s careless suggestion that her flight would allow her to meet ‘new friends’, this became a play about a move towards reconciliation, visualised (as is so common now for this play) as the lovers losing their clothes during their journey. This at times caused some quite unpleasant moments as the disrobing was at times clunky – the moment when Lysander simply pulled Helena’s skirt off went far beyond accidental farce to something much more problematic, and the disparity in the disrobing between the men choosing to take their clothes off and the women having their clothes removed was pronounced and uncomfortable. Much more effective, though, was the hilarious climactic encounter between all four lovers, during which Puck quietly and unobtrusively concocted a mud bath on the floor ready for the inevitable wrestling. The casual enjoyment with which he prepared to make a bad situation even more entertaining spoke volume’s about this production’s conception of the fairies as delighters in (harmless) mischief.

In keeping with the family atmosphere of the event, this was a platonic and inoffensive Dream, glossing over the more problematic aspects of the interactions (Lysander’s abuse of Hermia, Helena acting as a spaniel, the threats of execution, Theseus and Hippolyta’s squabbles) with light humour, and the more sexual and scatological jokes rendered family-friendly (although Flute’s kissing of Snout’s ‘stones’ and ‘hole’ was made wonderfully explicit). The Indian Boy was quietly led away from the fairy train by Oberon, Titania’s shock on awakening at seeing Bottom threw her more quickly and happily into Oberon’s arms, and the moment of regret as Egeus stormed offstage after Theseus declared Hermia could marry Lysander was acknowledged with only a brief and aborted gesture by Hermia towards her departing father. It was a reminder to me of how established readings of Dream that emphasise the play’s darkness have become, and what this production lost in edge it regained in joyfulness.

Yet surprisingly, given the emphasis on comedy, the Mechanicals were underplayed in favour of the lovers, even reversing the awakenings of the lovers and Bottom in order to make the lovers the climax to the forest’s escapades, at the cost of making it seem that Bottom was an obstacle to be cleared. The quiet and gentle comedy of the rehearsal scenes was in fact moving, particularly in Ted van Griethuysen’s Quince, whose nostalgic songs bespoke an old man gently trying to put on a good show. The quietness of these scenes left Bottom’s encounters with the fairies somewhat anti-climactic. his unobtrusive entry with the ass’s head a squandering of the big reveal. But the energy of the Mechanicals was being saved for an uproarious ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’. Quince soundtracked this chaotic performance with a gramophone playing music that cued silent slapstick (Thisbe running from the lion), heroic posturing (Pyramus flapping the cloak of his full Roman uniform) and elegiac melodrama (the lovers’ deaths). Avery Clark’s Flute was particularly entertaining here, wearing a full pink princess’s outfit and screeching in high-pitched tones before a surprisingly moving final collapse over Pyramus’s body. The interruptions of the nobles were more good-natured than usual, the whole performance happening in a spirit of good-natured, if amateurish, celebration.

The production’s final visual gambit was its most beautiful. As Theseus and Hippolyta kissed and the rest of the company left, the fairies entered to dress them again as Oberon and Titania. Philostrate took up a broom and began sweeping, before tearing off his butler’s uniform to reveal himself as Puck, and the fairies brought forward an eclectic selection of lights for Oberon and Titania to light with their touch. This final image of unity and concord brought a safe, but thoroughly enjoyable, Dream to a fittingly gentle end.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply