October 26, 2014, by Peter Kirwan

The Witch of Edmonton (RSC) @ The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon

(note – this review is of a preview performance)

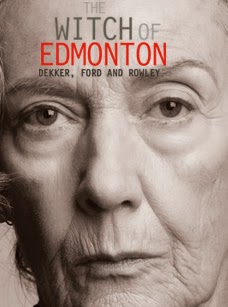

The Roaring Girls season, discussed in previous posts on this blog, ended with an entirely untypical coda. Directed by a man (Gregory Doran), given an early modern setting and appearing divorced from the statements about feminism and gender roles within the RSC that had characterised the rest of the season, The Witch of Edmonton‘s place in the season felt like a convenient rather than a coherent rationale. As the marketing material suggested, the production’s primary function was as a vehicle for Eileen Atkins‘ return to the RSC to work with Doran.

The Witch of Edmonton is an odd play to choose as a star vehicle, however, as the Witch herself, like Shylock, appears relatively briefly in only a handful of scenes. Atkins’ cantankerous Mother Sawyer bumbled and rambled, croaking curses at her persecutors and offering snappy retorts to the youngsters. Atkins did not seek the emotional vulnerability in the character, instead keeping her upright, indignant and dismissive of other characters, righteous according to her own principles. Even as she was taken off to be burned, Sawyer showed her disdain, barely looking at the onlookers as she spoke to them. With her tormentors blocked by guards, Atkins was allowed to hold the stage, a commanding presence even when (perhaps especially when) abandoned by Dog.

Atkins’ physical presence was effective in demonstrating the physical vulnerability of the character, however. When being beset by the villagers (waving firebrands – the RSC is perhaps to be commended for avoiding pitchforks, though this might have livened up the scenes further), her diminutive statue and inability to defend herself were immediately apparent. Particularly at the hands of Christopher Middleton’s Banks, the blows she received often drowned out her curses, and the violence addressed to her offered the opportunity for some comment (if unexplored) on the use of witchcraft to abuse women. While Sawyer here clearly delighted in her mischief, there was also a certain lack of awareness to her actions, driven by previous prejudice, that allowed her to at least partially become a victim alongside other characters.

The true evil here was Jay Simpson’s Dog, a malign and eerie presence. Simpson stood upright with his arms held out before him, lifting each leg and placing it precisely as he stalked the stage. His costume gave the impression of nakedness, the ears and tail evoking the impression of a dog but the full black body paint doing more to establish his aura. Dog was well-spoken and joyful, laughing freely at his victories and emerging from the forest of reeds that filled the upstage area. It was Dog’s presence rather than his actions that drove events – often he merely lingered upstage while murders happened, and sometimes appeared only suggestively in silhouette. While he could joke, his constant smile was used in maliciousness, not mirth.

The play trod a fine line between comedy and serious drama. Dog’s standout moment came as he stole Sackgut’s fiddle and led a Morris dance conducted at breakneck speed, forcing all assembled (including David Rintoul’s Sir Arthur) to jig at impossible speeds via some skilful choreography. The evocation of ‘The Devil Went Down to Georgia’ in the screeching of the fiddle was apt, a reminder that Dog was the Devil and that his anarchic influence was near-irresistible. Yet fascinatingly, Dafydd Llyr Thomas trumped Dog as Cuddy Banks, a clown with pudding-bowl haircut and an oblivious confidence. Dog was only flummoxed in his final scene when Cuddy lashed out at his behaviour, insisting he behave like a real dog and refusing to hear Dog’s responses. As Cuddy thrashed Dog offstage via the fields, there was a fascinating sense of discomfiture, as if the only person immune to the Devil was the only person foolish enough not to recognise him.

While the Witch and Dog are the inevitable points of interest when this play is revived, this production chose instead to make a star of Ian Bonar as Frank Thorney. Bonar, excellent elsewhere in this season, handled a complex role with superb skill. In early scenes he established rapport with the audience, neither asking sympathy for his bigamous plans nor ostracising the audience through indifference. His signs of anguish when left alone made clear that he was in over his head far too early, and he repeatedly made himself ridiculous through his abrupt dismissals of his wives following moments of apparently sincere tenderness (his accidental use of the wrong name to Faye Castelow’s Susan was a comic highlight). Castelow’s Susan and Shvorne Marks’s Winnifride provided excellent support, both upstanding women who exerted unbearable moral pressure on their vacillating love; and the production’s choice to end on the lonely reaction of Winnifride to events recalled the best of the domestic tragedies (especially A Yorkshire Tragedy) in emphasising the impact of events on the abandoned wife.

The audible shock throughout the auditorium to certain moments was, of course, a luxury that can only be enjoyed by relatively unknown plays, but Doran worked well not to reveal his hand too early. Sir Arthur’s early embrace of Winnifride and dominance of her were particularly effective, but the standout scene was the murder of Susan. Dog remained upstage, half-concealed and smirking, and Bonar allowed Frank’s anxiety to emerge from the conversation, becoming frustrated and irritable and then robotically committed to his task. The advantage of this was that it left Dog’s precise role ambiguous – was he engineering or simply enjoying this show? Susan reacted with strength and patience and, although the death itself was a little awkward in its performance, the moments of stabbing caused general consternation among the audience, and their locked embrace as they parted was the production’s emotional climax. Bonar followed this with a tremendous scene of self-abuse, slamming his head against a pillar, eliciting audible cries from the audience.

The pivotal bed scene was also effective, played against a black void that lit up twice to reveal the shadow of Dog among the reeds and the ethereal ghost of Susan. Against this evocative backdrop, Elspeth Brodie managed the relatively mundane discovery of the bloodied knife with quiet desperation and Bonar himself performed wonderfully from his horizontal position, holding up his hands to ward off the imagined and real corpses and flailing as he found himself finally unable to excuse his behaviours. This led to a moving final meeting with his father (Geoffrey Freshwater) in which the two men embraced and sunk together to their knees in a tearful parting.

While the production was filled with fine moments, the whole felt to me a little staid, a straightforward and sensible staging of the play without excessive comment that took quite a while to build up momentum. This is partly a fault of a play that establishes a great many characters early on and then invests little in them (it was no fault of Joseph Arkley and Joe Bannister that Warbeck and Somerton have little to do following their initial banter) and that depends so much on a conjuring clown whose jokes hold no candle to those of, say, Faustus. Yet as a haunting period piece following a community turned upside down by a malign presence, this production nailed the elegiac tone and suggested that the play’s victims were legion, ending on a downbeat note of universal defeat.

[…] by contrast with Shakespeare’s witches. As Peter Kirwan comments in his review of the play in The Bardathon, “The Witch of Edmonton is an odd play to choose as a star vehicle”. It isn’t the […]