May 24, 2014, by Peter Kirwan

I, Malvolio (Tim Crouch) @ Curve

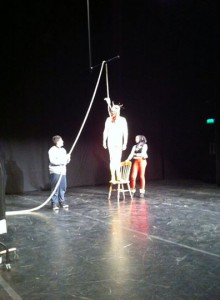

I, Malvolio is one of the bravest shows I have seen in some time. How many pieces of theatre invite two young children to come on stage to hold a rope and kick out a chair while the title character prepares to hang himself? Although it carried an age warning of 11+, Tim Crouch’s one-man show challenged rather than pandered, confronting its audience with potentially horrific images and erudite, verbose narrative, demanding (often explicitly and confrontationally) an attentive and responsive engagement.

The setup was deceptively straightforward. Malvolio (Crouch) was already onstage in soiled and torn underclothes (causing cries of dismay from the children when he bent over and revealed his backside), wearing a fools cap and a ‘Turkey Cock’ sign on his back. He muttered and mumbled, repeating ‘I’m not mad’ again and again. The first half of the hour-long performance saw him antagonise the audience, inciting laughter at his state and railing against debauchery, mess, un-Christian behaviours and modern life, until a hanging attempt that he aborted. Then, as he dressed himself in his steward’s clothes, he proceeded to tell the story of Twelfth Night, pointing out the madness of that play while occasionally breaking as he realised Olivia had found love.

It was a shame that Crouch seemed to be genuinely struggling with this particular audience. On a Saturday matinee, Curve’s Studio was poorly attended, and then mostly with quite young children. Increasingly, Crouch/Malvolio addressed the fact that the audience weren’t responding as they usually did and, eventually, even began commenting that the whole afternoon had gone to pot, which was rather dispiriting as an audience member. There were two key difficulties here. The first is that the ‘role’ Crouch/Malvolio demanded was one of cruel laughter – as he explicitly pointed out, the dynamic of the narrative was that the audience would laugh at him, and that he would then upbraid them for their laughter. Yet the tone of the piece at least partially precluded that. Crouch was expert at presenting the arrogant, sneering, unpleasant Malvolio (particularly tearing into latecomers); yet he was also deeply affecting from the start in his moments of suppressed emotion when mentioning Olivia. As a result, the play (rightly, I felt) incited no all-out response from its audience, either of joyous laughter, of outrage or of sympathy. Given a small audience, I can’t help but feel that a quiet reaction mediating between these was inevitable – if this audience was expected to play the part of laughing cruelly, it seemed to need more incitement.

Secondly, Crouch himself got confused at one point, telling an audience off for enjoying something they were meant to not enjoy; then realising that he’d got it the wrong way round. At this point he forgot his lines and took a while to get back into the role. While this was an obvious mistake, the problem here was of course that it highlighted the very fact that this play was too subtle to generate homogeneous responses, to a point where even the performer in the heat of the moment could forget which way the dynamic was tending. While Crouch and his directing team (Karl James and Andy Smith) are clearly attentive to the problems of complex audience response, the surface-level script assumes a relatively prescribed set of responses, and Crouch’s repeated meta-commentary on how the performance was going served to further confuse rather than unite the audience.

This may sound overly critical, which it is not intended to be; but a play so dependent on forcing an audience to confront its own (cruel, derisory) responses needs to ensure that it generates those responses. Crouch was most successful when engaging in full-on humiliation of his audience – and yes, this audience member (described by Crouch as ‘purse-lipped’, which in my defence is less about my enjoyment level than to do with the extreme physical pain I’d been in all day and was trying not to be distracted by) was dragged onstage to help Malvolio put on his shoes (which I did fairly efficiently, if I say so myself), and a poor young girl was put through the mill in her abject failure to pull his jacket over his arms.

This play was, of course, about spectatorship and complicity. The audience was invited to take photos as Malvolio threatened to hang himself (mine is posted above) and share them freely, before Malvolio screamed at us all that he wouldn’t give us the satisfaction. His spectacular monologuing, particularly as he reeled off a skilful set of insults and pet peeves, was designed to infuriate and entertain simultaneously, turning him into an exaggerated figure of comic pomposity, deflated continually by his g-string, a ‘kick me’ sign on his back and his attempts to dress himself. The play invited its audience to judge themselves for what they (aligned with Sir Toby) had done to him, for the way they had bullied and humiliated him while the rest of the characters had gone on to happiness.

The difficulty I have with this is that the play allowed too much sympathy for Malvolio from the start, especially for those of us familiar with Twelfth Night; my gut reaction was one of compassion for a man who had clearly been publicly humiliated and was now choosing to lash out in relatively harmless ways. It was hard to tell whether or not this might have been an anticipated facet of the production, buried beneath the explicitly planned mocking and counter-mocking – while the play seemed to want its audience to reflect on its own behaviours as complicit bullies, might it also (and perhaps more pointedly) have been trying to say something about the way in which we perform our sympathy and allow the wronged a platform, even if it’s a platform that damages them? Could I, Malvolio, in a situation such as this afternoon’s matinee, have more to say about the kind of attitude that turns Katie Price’s live-break-up on Twitter into public entertainment, than about cultures of complicit harrassment?

Whether this is the case or not, Crouch’s piece was provocative and expertly performed, even if Crouch himself seemed increasingly frustrated by an audience that wasn’t playing along. Yet the ending reclaimed a potent power as Malvolio told the audience his final revenge would be to leave them hanging in unfulfilled anticipation, forcing everyone to sit up straight before leaving the stage and not returning for applause. As audience members one by one got up and left the auditorium, it was difficult to gauge what kind of impact the play had had. For this reviewer, the theory worked better than the practice, with a polite and small audience clearly not generating the fully combative (or perhaps more pliant?) attitude that Crouch/Malvolio seemed to want. Yet as Malvolio grew back into his steward’s finery and abandoned his audience, it was possible to see the potential of a play that, ultimately, questioned the purpose of theatre itself, if all we want is to be entertained at the cost of others.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply