December 17, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

Henry V (Michael Grandage Company) @ The Noel Coward Theatre

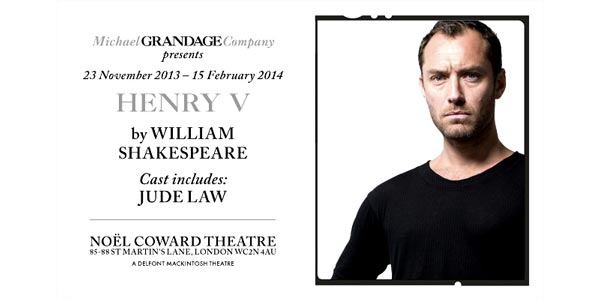

Following the underwhelming and frustratingly conservative Midsummer Night’s Dream, I didn’t have high hopes for the second Shakespeare in Michael Grandage’s West End season. With promotion once again based entirely around a celebrity actor (Jude Law, returning to the director-actor partnership of Hamlet), a theatre and audience unsuited to the interventionist or radical political readings possible with this play, and a lack of other history plays to provide it with context, Henry V could once again have offered an entry-level, Shakespeare-for-Shakespeare’s-sake crowd pleaser and nothing more.

At times, this seemed to be the case as ideas were presented and dropped with little coherence. The excellent Ashley Zhangazha doubled as the Chorus and the Boy, slipping in and out of the action wearing a backpack and being killed messily onstage, leading to the omission of the Act 5 Chorus – yet the Epilogue failed to pick up on the potential of this ghostly commentator, the Chorus seemingly none the worse for his unfortunate murder. The assorted quarrels (Fluellen-MacMorris, Fluellen-Williams, Pistol-Fluellen) all ended with a form of accord, dispelling tension, and any critiques of the King remained firmly in their moment, rather than building into a sustained statement. That is, there was nothing obvious that this production wanted to say about its play, choosing instead to play the individual moments for themselves.

While this felt like a missed opportunity, however, there was no denying that this production worked excellently on its own terms, offering a fast and clear take on the play that showcased some fine performances and rarely failed to entertain. Grandage’s strength remains the direction of actors on a bare stage, and the power of Zhangazha’s crescendo through the Act 3 Chorus, the sounds of battle building up behind him, evoked all the excitement, fear and energy one would expect from a young man’s first foray into war.

Law made for an uncertain King at first, sometimes indistinguishable from his nobles as he stood in lines or groups with them, neither asserting presence or differentiating himself. This Henry was a man of his people, perennially leaning forward to engage closely with his addressees and clasping hands on shoulders. Led by emotion, the decisions to order the deaths of Bardolph, the treacherous lords and the French prisoners all involved conflict and a personal feeling of betrayal. As Cambridge and Scroop protested their relief at being caught, Law screamed in retaliation at them, ordering them to be marched to their deaths (in, incidentally, one of the most clumsily blocked marchings-off I’ve ever seen).

Law’s personal approach worked wonders in moments of intimacy, though. Both of the big set speeches were utterly convincing as Henry worked his way around his men, clasping shoulders and looking them steadily in the eye, emphasising words of honour and courage, using his haunched shoulders to encourage his men into readiness also. As their spirits rose, the men began stamping on the floor or banging their swords together, creating a percussive underscore to Law’s rhythmic delivery that built effectively into the climactic embraces and battle roars that saw the English launch into Harfleur and Agincourt. In another sequence, the Governor of Harfleur was cowed into submission with Henry’s men snapping, growling and thumping in time with their leader. In moments such as these Law perfectly captured a sense of Henry as charismatic leader.

As lover, he was even more convincing. The final scene was played in full and indulgently, but an indulgence that was earned. Henry shifted nervously from foot to foot while Jessie Buckley’s Katharine stood, still and poised. Henry’s growing exasperation manifested in expertly timed bathetic remarks, including his final appeal to the audience of ‘Can any of your neighbours tell!?’ He lapsed into a blunt drawl for his plain speaking, and mocked himself openly as he dabbled in French, with Katharine’s cold demeanour finally cracking as his appealing charm worked on her. Referencing and undermining his own movie-star looks, Henry demonstrated his ability to make himself whatever he needed to be.

The performances across the rest of the company were strong and, while no overall arc became clear, individual scenes yielded plenty of insights. The French-speaking scene was amusing, with the bawdy homophones of ‘foot’ and ‘coun’ made very clear to Katharine’s shock. The scene in the French camp before Agincourt was another comic highlight, as Ben Lloyd-Hughes’s Dauphin mimed riding his horse and boasting until Ian Drysdale’s Constable and he came nearly to blows. Prasanna Puwanarajah made for a formal and somewhat smug, if gracious, Montjoy.

The Eastcheap scenes included a long silence in honour of Falstaff’s death, though I wonder how comprehensible these scenes would have been to an audience new to the history plays, as the back story was not foregrounded (later, Henry’s heaven-raised eyes after the order of the hanging were the only allusion to his previous relationship with Bardolph). The lively performances in the subplot worked well, Norman Bowman’s Nym in particular lending some pathos to his refusal to kiss Mistress Quickly. The highlight here was Ron Cook’s elderly, swaggering and undiminished Pistol. Even in his final appearance, he remained cocksure as he left the stage to begin his life of pick pocketing, allowing a moment to reference Nell’s death before reviving himself. The sadness of the character was not overplayed, but left significant enough to ensure at least the beginnings of a question.

Matt Ryan’s Fluellen completed a strong ensemble, his loud and amusing performance bringing heart and personality to the battle scenes, albeit sometimes with a tendency to overcompensate (particularly in the aggression of the Monmouth speech after the killing of the boys). Given the formality of James Laurenson’s brusque Exeter and Edward Harrison’s nervy Westmoreland, Ryan offered a down-to-earth levelling effect throughout, even forcing a smile from Henry following the final battle. His treatment of Pistol in their final scene was brutal, but his energy in his encounter with Williams was amusing and lent the scene a genuine frisson of danger as Fluellen called for the man’s hanging.

Slightly less than the sum of its parts, this Henry V was nonetheless more than the unchallenging approach implied. While the ominous choice to end the final Chorus on ‘made his England bleed’ was unearned, the production presented the play’s many questions and positions in a way that privileged none, instead offering a series of snapshots of the experience of war that rarely paused for breath. It’s the first major Henry V for a while that has stood alone without Hal’s backstory, and made a fine case for the play’s continued presence on the non-specialist stage.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply