December 5, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

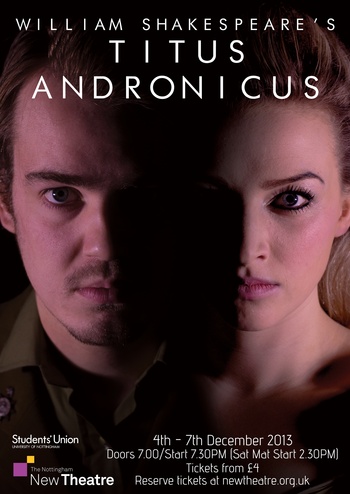

Titus Andronicus (New Theatre) @ The New Theatre, Nottingham

I’ve spent much of the last week sticking up post-it notes on posters for the New Theatre’s production of Titus Andronicus, adding ‘and George Peele’s’ after the headline banner ‘William Shakespeare’s’. Titus still feels like a discovery when revived, a first for many of its audiences, and recent issues such as the authorship question (which suggests that Peele wrote most of the play’s opening act) are still obscure to non-specialist audiences. In James McAndrew’s production for my university’s student theatre, the priority was clearly on narrative clarity, ensuring its audience could follow the play’s twists and turns, while balancing on the knife-edge between comedy and horror. With a game cast and some excellent decisions, it succeeded admirably.

Performed in a rough modern dress, the production aimed to find an emotional truth amid the high rhetoric and heightened situations. Key to this was Nick Barker’s Titus, broken by the loss of twenty-one of his sons in war and already emotional at the production’s opening. Barker anchored the production with a fine arc, escalating through various stages of grief until the loss of his hand, at which he finally broke into laughter. Barker’s matter-of-fact delivery grounded the more outlandish scenes of the second half, his detached deadpan particularly strong when confronted with the pantomimic arm waving of ‘Revenge’ and her sons. In this reading, Titus was a man pushed to and past the point of endurance in his pain, leaving a sardonic but suicidal – and therefore dangerous – husk to bring the play’s events to its conclusion.

Starting the play at a point of grief allowed the production to emphasise a domesticity that became dominant in the second half, in which a huge dining room table formed a permanent set. From the first burial of the (unseen) dead sons, before a flat engraved with Latin phrases, the emotional connection of Titus to his family was prominent, particularly as his reunion with Lavinia was played as a private rather than public scene. Titus was father first and foremost, with his military nature more concealed – Lyle Fulton’s fatigue-clad Lucius was the more obvious general. While this enabled a human connection to Titus, however, it made little sense of his actions in killing Mutius and electing the debauched and irresponsible Saturnine. By stripping Titus of the unsentimental duty that drives these actions in the play, they instead became merely the fatal mistakes of a man absorbed by his own grief, a decision which somewhat trivialised his fall from public favour.

Although Titus anchored the play, the strength of the ensemble cast made for some delicious competition for attention. Ajay Stevenson played a partially blackfaced Aaron, the right side of his face and left arm darkened. He bantered with the audience, drew out his lines and assumed an iconic dominance of the stage, particularly during his striking gallows speech, positioned standing on the dining table before a noose. Aaron’s smooth tones and careful delivery were sometimes ponderous (particularly in the time it took to kill the Nurse, a scene I’ve never before seen take up so much stage time), but served to stress this character’s centrality to the cycle of destruction. He was complemented by energetic performances from David Porter and Alfie Cranmer as Chiron and Demetrius, who wrestled viscerally and veered between dithering and leering according to the confidence Aaron engendered in them.

Ginny Lee’s Tamora towered over her various lovers, striding about the stage on enormous shoes and adopting a confident, controlling attitude, particularly over her gullible new husband. This Tamora had a sense of humour: her sideways glances at the audience during Titus’s ‘mad’ scene were hysterical, and her floaty performance as Revenge turned quickly to embarrassment as Marcus entered. Her preference was to feign innocence, as when delivering the incriminating letter to Saturnine slowly following the discovery of Bassianus’ body. Her finest moment, however, was immediately preceding Lavinia’s rape. Cressida McGill gave an impassioned series of pleas, throwing herself at Tamora’s feet as her attackers laughingly disrobed themselves in preparation. Tamora maintained perfect poise, allowing hints of hope to linger before snatching them away, and finally turning to leave the girl to her fate. The subsequent reveal of Lavinia in a spotlight, spitting blood and gurgling, was the play’s most effective visual moment and effectively prepared for by this cold abandonment.

Balancing the play’s horror and humour is perhaps the most difficult task for any team producing Titus. As far as humour goes, there were only two serious misjudgements. Making the Nurse a flat-out comedienne (no fault of Penny Bainbridge, who was exceptionally funny as a blunt Lancastrian oblivious to the effect of her words) destroyed the impact of Aaron’s impassioned plea on behalf of his child’s right to exist, leaving the wit of his repartee and the serious import of his words lost among laughter at the Nurse’s exaggerated reactions. And there is a reason that most productions of Titus don’t require Lavinia to pick up Titus’s hand with her teeth until immediately before she exits – to leave her standing there for several minutes with a hand in her mouth is to invite a hysterical audience to drown out everything else in the scene, a huge disservice to the departing defiance of the excellent Lyle Fulton, whose passionate and formidable Lucius was one of the play’s strongest aspects.

Elsewhere, however, the comedy was well-judged. Aaron brought himself to the Goths and knelt for admittance, but on realising he had prostrated himself before Lucius moaned in a perfectly timed ‘not again’ reaction. Another highlight saw Titus and his followers ascend the steps on either side of the audience to throw paper planes with messages at the dining royal family, and even the stoic Marcus (Ben Williamson) showed himself able to laugh. The fly scene was measured, and the final orgy of violence played with a light but not parodic touch, maintaining the more ludicrous aspects without losing the weight of the killings. The absolute standout in the humour stakes was Nick Gill (incidentally, according to his bio, from my neck of the woods in Birkenhead) as a diminutive and outlandish Saturnine. This spoiled brat was already out of control before the elections, and upon gaining his laurel wreath immediately sprawled across his throne. He drank and giggled, responded boyishly to Tamora’s caresses, stamped his feet and never missed a comic beat as he whined his orders. Yet even here the character stayed clear of caricature, retaining in the final scene something of quiet shock at Titus’s brutal snapping of Lavinia’s neck.

The horror was well handled too, the copious stage blood not drowning the stage. Careful lighting design and a decision to only reveal Lavinia slowly following her rape placed much of the onus for interpretation on Williamson’s Marcus, and the ominous build-up to the act has already been singled out. I would have liked to see a little less recourse to histrionics and a little more of the play’s acknowledge stoicism – there was a sense that, at times, less could have been more as characters struggled to understand the horrors they were undergoing. In this, it was Barker who once again led, his increasing detachment offering the perfect counter to the high emotion elsewhere. A powerful moment came as Marcus finally roared for vengeance, and Titus simply laughed quietly back.

In trying to manage the balance between humour and horror, though, my only substantial complaint emerges – the lighting. While at times, such as during Lavinia’s reveal, the lighting was used to great effect, for the most part this was one of the most frustrating technical productions I’ve ever seen. Lights were used as if the production was attempting to direct a film, flicking between several different states during every scene as spots and cross-fades were used to indicate asides, soliloquies, significant plot points, character moments, emotional reactions and any other slight change in tone. This played havoc with the spatial logic of the stage, creating multiple environments and slowing down the action to a crawl usually more associated with frequent scene changes. It was a shame, as it betrayed a lack of confidence in the clarity of delivery, when in truth this production could easily rely on its strong ensemble to communicate the shifts in mood and tone, instead of putting lights and actors into direct conflict with one another.

In taking on such a little-known play, cast and crew did the New Theatre proud with a clear, confident and balanced production filled with striking images and comic beats. It was also the straightest production of the play I’ve ever seen, avoiding strong interpretive angles in favour of simple storytelling, though a development as the run progresses might make more of the trauma angle that emerged strongly during Titus’s later scenes and the pivotal confrontation between Lucius and Aaron, where a concern with the nature of justice and the extent of revenge offered potential for incisive commentary. In going some way to domesticating the issues of this very public play, the team found a fascinating set of personal dynamics underscoring the larger events, leading ultimately back to the question of personal loss and personal grief which drove Titus to, in a moment of weakness, select the older brother. It’s a potent, honest and troubling idea, that over-involvement in one’s own grief can destroy more than just the mourner, and a downbeat ending offered little hope for the future.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply