November 4, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

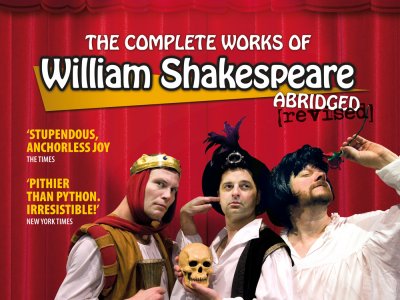

The Complete Works of Shakespeare Abridged [Revised] (Reduced Shakespeare Company) @ Nottingham Playhouse

It would be churlish to react with academic indignation to The Complete Works of Shakespeare Abridged. The Reduced Shakespeare Company has existed for longer than I’ve been alive, and the Complete Works itself for twenty-six years. While the show may continue to present itself as a radical overturning of Shakespearean/British snobbery and a riotous romp through an otherwise po-faced Shakespearean institution, the attitudes being attacked in this show remain decidedly those of the ’80s. In many ways, the play’s irreverence has itself become institutional, and as the current ‘[Revised]’ manifestation shows, the text itself has remained almost entirely fixed for that entire period. One doesn’t go to see the RSC (this one) for radical insight; one goes to watch an established show go through its well-rehearsed motions.

Despite the ribbing and complaints, The Complete Works comes from a place of deep love for Shakespeare, and having seen this following a day’s meetings about projects based on fan behaviours and creative play with institutional texts, it was hard not to see the current production in that vein. Whether turning Titus Andronicus into a cookery show (complete with Titus and Lavinia attempting to high-five), replaying the Histories as an American football match (with Lear being sent off for being fictional) or adding a skit about The Two Noble Kinsmen based on its modern geopolitical framing (‘no, it’s not the two MOBILE kinsmen’), the script played consistently both to casual punters and hardened fans. As with any parody, the joy came from the shared experience of recognition and re-creation.

The problem, of course, is that with such an established text, it was hard not to be aware of the lack of spontaneity on display. Gary Fannin, Simon Cole and William Meredith gave it their all, but the rehearsed spontaneity was stuck in cycles of repetition. The production’s funniest moments came as the performers themselves corpsed or improvised, particularly as one actor mispronounced ‘folks’ in addressing the galleries and struggled desperately to recover, or another’s weak joke fell flat to the merciless mockery of the others. Instances such as these injected a much needed liveness to a script that has outworn its duration, and the rather desperate updatings (the Shakespearean professor is revealed to be a Belieber; references to Lady Gaga) only highlighted this further. Far more effective were the mocking references to the Playhouse’s current production (‘if you enjoyed this, tell all your friends. If you didn’t – this was Richard III‘) and the sincere pleas before the encore for support for the Playhouse’s current projects. I couldn’t help but wish for less of the play and more of the actors.

This was the first time I’ve seen the show, despite having read it, and in performance some of the play’s more subtle insights came out. The resistance to self-serving psychological portrayals of characters was strong, mocked throughout by the actors who relied in the brevity of the playlets on stock figures, pantomime types and representative costumes. While the actors situated themselves as bolshy Americans sending up an English institution, the work carried out here was in fact the inverse of that undertaken by Al Pacino in Looking for Richard, pointing to Shakespeare’s reliance on established tropes that reached its nadir in the Company’s amalgamation of all sixteen comedy plays into a single romance plot. While the running jokes about one actor constantly donning the same wig, mannerisms and vomiting death for all of the female characters got tired, it also acted as a bathetic counter to the overly psychologised treatments of characters sent up beautifully by getting one poor victim out of the audience to scream as Ophelia while the audience collectively took on her ego, id and superego by screaming motivations at her.

Perhaps more significantly, despite the play’s age, it still has clear purpose. In a time when Julian Fellowes, Nick Hytner and more are complaining about Shakespeare’s lack of accessibility, a play that confronts and performs its own reductive approach to Shakespeare while simultaneously pointing to the flaws in that approach (giving the production credit here for its own self-awareness…) arguably offers some redress. I’d like to believe that this performance acted as a middle finger both to self-appointed guardians of Shakespeare and to those who insist it needs dumbing down: the enthusiastic response to this performance was based, of course, on a theatre company’s tireless commitment to meeting an audience on its own level and only patronising them when joking about being patronising. How far it was successful I’m not sure, but I imagine it’s difficult to get that enthusiastic about hating Shakespeare.

I’m responding informally to this production because it acts as a fascinating challenge to my own position as theatre reviewer. To critique this production on scholarly terms is also to fall into the trap of being the academic target of the production, and to review it on its own terms is, in some ways, to be uncritical. Fascinatingly, I found it impossible to watch this production in either spirit, instead enjoying it on one level as a meta-theatrical commentary on the theatre’s own fears and expectations for Shakespeare, and on another as a bizarre and problematic example of a living time capsule, dependent on its local audience engagement for validity yet entirely unresponsive to the changes in relationships with Shakespeare over the decades since it was written. There’s much more to be considered here.

I’ve never seen this show, but it strikes me that it can be compared with Tom Lehrer’s song about the periodic table in that it’s a playful summary of a valued dataset.