September 16, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

The Birth of Merlin (Read Not Dead) @ Shakespeare’s Globe

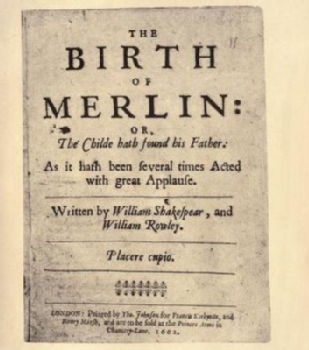

Of the fourteen plays included in C.F. Tucker Brooke’s Shakespeare Apocrypha in 1908 (to be supplanted next month by the RSC Collaborative Plays by Shakespeare and Others, in which I’ve had a hand), I’ve now seen six: The Two Noble Kinsmen (twice), Thomas More, Arden of Faversham (twice), A Yorkshire Tragedy (twice), Fair Em and now this, William Rowley’s The Birth of Merlin. Fascinatingly, while Rowley’s play has one of the least plausible cases for a Shakespearean involvement – it appears to have been written in 1622 – it shares rich connections with other plays in the Apocrypha, reprising the early British dynastic politics of Locrine, featuring the abstinence from marriage of women in a similar vein to The London Prodigal, and combining elements of woodland romance, clowning and wandering princes in a manner that evoke the ever-popular Mucedorus (for which, see my recent article in this book). It’s also one of the more inventive and amusing comedies of its period.

The Read not Dead team has excelled in comic romance this year, particularly in its definitive renditions of The Knight of the Burning Pestle and the closely related Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. It’s great to see a company so used to one another engaging in ensemble casting: Matt Houlihan in particular seems fated to keep playing the second-rate conjurer, here dying in a wonderful piece of slapstick involving a precariously balanced wooden box and a casual lean on an unstable wall. The style is well-established – an ironic detachment showing awareness of the more ridiculous aspects, a puncturing of grandeur and a DIY approach to props ranging from the paper bird that was inexplicably waved in the audiences’ faces at the show’s start to the Christmas tree star that stood for the portentous comet of the play’s climax.

The Birth of Merlin interweaves three plots, all of which rewarded attention. Perhaps the most difficult is the story of Donobert’s attempts to marry off his two daughters, a plot which is dropped halfway through and only wrapped up very briefly at the play’s end. The pleasures of Colin Blumeneau’s outraged Donobert’s and David Meyer’s dithering Gloucester were apparent, but here the real fun was watching Adam Cunis’s cocksure Edwin deflated in his expectation, to be followed by Robert Heard’s Cador. The main scene of this plot saw Frances Marshall’s pious and earnest Modestia shunned by the wedding procession of her sister, yet finally turning the scene around through her pleas until Claire Chate’s Constantia broke herself away from her shocked fiancé to cheers from the audience.

This is an odd story in that the sisters remain chaste at the play’s end, with the only consolation for the jilted lovers being their adoption by Donobert as his heirs, in a rather sweet gesture of male solidarity. It is Rowley’s fault rather than the production’s that the importance of this gesture, and of the friar’s assertion that the church will not force a marriage, didn’t carry greater prominence, but this inversion of conventional values resounded throughout the other plots.

In the main plot, Mark Hammersley played the lovelorn Uter Pendragon (here still a prince) as a light parody of the romantic hero, dramatically melancholic in the woods and booming with self-righteousness when wooing Lizzie Phillips’s femme fatale Artesia. Phillips has a knack with an ambivalent smile that here made her particularly villainous, even when not stalking round her suitors or laughing maniacally as led off to her death. Peter Basham as Aurelius was a suited and upright ruler, but a belligerent one, unheeding of the muttered advice of his nobles.

John Gregor as the soldier Edoll was the catalyst for the court scenes, marching in wearing camouflage gear and refusing to compromise. What impressed here was the swift development and clarity of the battlelines as they were drawn, as Uter and Aurelius faced off before Edoll arrived on Uter’s side and Ostorius and Octa on the other. The escalation of violence was defused dramatically by the arrival of Merlin, when fate overtook intrigue and events began being steered by outside forces, beginning with the death of Proximus by falling stone and continuing through prophecies and inevitable deaths, faced stoically by Tim Treloar’s Vortiger.

This was the arc to which the third plot line tended, the one by far most distinctive to the play. Sam Cox made for a dour, miserabilist Clown, in bobble hat and anorak, delivering his lines in the rhythmic and relatively uninflected patter favoured by current Globe comedians. The reading’s co-ordinator Martin Hodgson, meanwhile, had cast himself as his sister Joan Goe-Too’t: heavily pregnant, she wore wellies, frumpy cardigan and huge glasses, and pushed her cheeks out while pursed lips indicated her randiness for every man that crossed her path. The double act was frequently hysterical, including an unforgettable moment of corpsing as, following a prompt from Cox, Hodgson announced ‘I’m milking it – all new mothers lactate’ which brought the house down. One could see in the irreverent performance the genius of Rowley’s comic writing, from Martin Lamb’s amusingly effete performance as Nichodemus Nothing to the flailing escape of Jamie Askill’s Oswold (an unsung hero of these events, Askill was never less than hysterical in his series of insecure messengers, courtiers and soldiers). The jarring note was that offered by the play, as the accused Uter hit and then began throttling the pregnant Joan, a difficult image to pass off as amusing even in this context.

The shift from Hodgson’s coy waves and Cox’s laconic stylings to the darker and more spectacular matter of the comic plot was heralded by the arrival of James Wallace’s stately Devil, in wraparound shades, long black jacket and horns. Walking slowly and threateningly, Wallace was a compelling and irresistible presence, both enticing and terrifying the silly Joan. The play’s first half closed with his summoning of four female spirits to enact the birth of Merlin in a frankly disturbing scene where Joan sang and span while two shrouded demons pulled a mewling series of blankets from under her dress. Wallace’s evil became even clearer in his second attempt to rape Joan, bringing out another masked devil to pin her arms down while he reached for her crotch.

David Oakes’s arrival as Merlin marked a sea change in the text that brought together the plots and began shaping them into a higher narrative. On a literal level, his silencing of Cox’s Clown (who continued to mumble) and his matter of fact prophecies of Vortiger’s doom quietened and gave order to the action, forestalling the escalation of earlier. Providence took a more prominent role, mostly replacing humour (although the two growling ‘dragons’ dressed in red and white ribbons received one of the biggest laughs as the loser ran off yelping). Oakes was calm, enigmatic and barefoot, moving to the centre of the stage and explicating signs in long soliloquies that culminated finally in the presentation of an enthroned Arthur surrounded by other kings kneeling, and appeals to the national spirit. If the production made nothing else clear, it’s that Merlin’s arrival irrevocably shifted the direction of the country.

The repeated insistence on the Child finding his Father came to a head as Merlin and the Devil faced off, Wallace articulating a hilariously menacing ‘Merlin’ of recognition which simultaneously evoked Darth Vader, Inigo Montoya and every Western ever made, to the audience’s delight. There was even time, following Wallace’s wafting off stage, for a moment of tenderness as Merlin promised to establish Stonehenge as his mother’s final resting place. In moments such as this, the Read not Dead team realised the potential of Rowley’s chaotic and surprising play as a foundational British myth rooted in the unexpectedly fleshed out adventures of a very human group of misfits.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply