August 12, 2012, by Peter Kirwan

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (As You Like It) (Dmitry Krymov’s Laboratory) @ The Royal Shakespeare Theatre

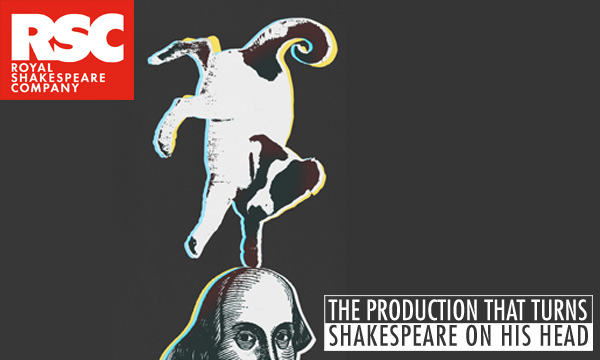

The programme for Dmitry Krymov’s production, a special commission for the World Shakespeare Festival, depicts an acrobatic Jack Russell Terrier balancing on one paw on top of Shakespeare’s head. It is an image that says everything and nothing about the production that “turns Shakespeare on his head”, speaking to the conscious irreverence of the company’s approach. The play’s double title was itself an act of misdirection, the “As You Like It” perhaps more appropriately glossed as “if you like”. Apart from the promise of Venya-the aforementioned performing dog-this was a production that revelled in its surprises and secrets.

This collaborative Russian-language piece, bringing together the Chekhov Festival and director Krymov’s experimental laboratory based at the Moscow School of Dramatic Art, took as its theme the final act of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The Royal Shakespeare Theatre was covered in plastic sheeting and sawdust, into which unfinished space an enormous company of clowns, technicians and actors struggled to drag spectacular pieces of scenery. Sprawling branches, an enormous tree trunk and a gushing fountain appeared and were taken offstage, never to appear again. As they bickered, a captioned ‘translation’ informed us that the Mechanicals were debating the thematic and linguistic complexities of Pyramus and Thisbe, establishing straightaway an idea of comically distrustful mediation. The self-awareness of the production was its own theme, a deconstructed process of establishing and immediately challenging its own identity.

In sequence, a long train of finely dressed audience members were escorted onto the stage and to boxes and balconies on either side (at its peak, about fifty performers shared the stage). These nobles turned up their noses distastefully at the ramshackle arrangements. Standing for the wedding guests of Shakespeare’s play, the rude guests proceeded to answer their mobile phones, interject with personal anecdotes (causing the production to halt at awkward moments) and criticise the arrangements loudly, providing an ongoing framework for the play that turned interpretation itself into a performance, the spectators increasingly involved in the spectacle.

Meanwhile the Mechanicals donned tuxedos and one apologised for the ramshackle nature of the performance, though pointed out that there was no way for the audience to know whether or not this was deliberate or a matter of exigency. This was the game that the paying audience was asked to play along with the on-stage spectators; was this seemingly random assemblage of images, physical comedy, puppetry, music and apparent improvisation as random as it appeared? Was this show incomplete, or was its incompleteness, in fact, the point?

The main action, inasfar as the main action could be separated from the other layers of performance, concerned two ten-foot high puppets of Pyramus and Thisbe, manipulated by the company and made up of scraps, with grasping metal fingers. A narrator informed the audience that the company had decided on Pyramus and Thisbe as a story of pure love, and their meeting and wooing was played out at length. Male and female operatic singers “voiced” the puppets as they moved clumsily around the stage. “Pyramus”, with a cut-out image of a youthful boy for a head, gathered a bouquet from various bunches of flowers held up by clowns in various extraordinary poses – one standing on another’s shoulders, one balancing on his head on top of another’s head and holding the bouquet with his foot, one wobbling on top of a stack of four precariously balanced cylinders.

The combination of humour as the Mechanicals attempted to maintain control of their puppets and wonder at the physical dexterity of the clowns served to heighten the meeting of the lovers, turning a simple romance into something more transcendent. At first this was undercut with deliberate crudity. The puppets sat together as Venya performed for them, and Pyramus fed assorted fruits to Thisbe whose head unhinged, as if a dustbin lid, to swallow the food whole. The onstage audience finally erupted in disapproval as Pyramus’s crotch panel was unscrewed to reveal an enormous phallic balloon that the Mechanicals pumped up.

However, as the lovers parted following the outrage of the spectators, the production’s tone shifted. Thisbe was attacked by a lion, a costumed actor with enormous dragon’s wings, who was dragged back by other performers. Venya barked in defence of Thisbe, and an actor tore off strips of her skirts and scattered them on the floor, interspersed with strips of red. As she left the stage, the lights fell, the singers sang and a moon rose behind the back curtain, through which Pyramus slowly emerged. In an extraordinarily moving sequence, Pyramus discovered the bloodied strips and the puppet exploded, arms and torso being carried to different corners of the stage and coming back together three times. Each time, Pyramus’s face had changed, becoming increasingly aged and bearded. Finally, he thrust a sword into his stomach and the puppet was left in a pile for Thisbe to discover, flanked by four puppet swans who lamented alongside her.

The pathos was, once again, undercut by the Mechanicals, who performed a ridiculous noise collage of shrieks and shrill singing, before being joined by four ballet dancers who performed the cygnets’ famous steps from Swan Lake while the rest of the company broke up and began chatting and laughing with their onstage audience. An old Mechanical began sweeping the stage with a broom instantly recognisable as Puck’s, forcing the dancers to skip about. As she departed, one of the onstage audience members had a simple moment of reunion with her Puck, suggesting they reunite for another show. The play stumbled to a close in this combination of beautiful images juxtaposed with the mundane, seeking the universal story buried under the momentary spectacle. Capturing the spirit of Dream, this collage of stunning visual images, extraordinary physical performances, evocative music and a dancing dog ultimately exposed the art of storytelling itself. Its studied artlessness belied the detailed craft on display in a deliberate strategy, designed to best show the production’s heart in an evocation of love and laughter.

The original version of this blog can be found on the “Year of Shakespeare” site: http://bloggingshakespeare.com/year-of-shakespeare-a-midsummer-nights-dream-as-you-like-it

Not seen this production but it sounds as if the ending is at least in part referencing Firs at the end of The Cherry Orchard. In fact from your description I wonder if there may be other Chekhovian references. Just a thought.

Not impossible Ray, though I have to say I don’t see it myself. Krymov’s style involves a great deal of collage and quotation, however, so it’s certainly possible.

[…] Merchant of Venice, the Isango Ensemble’s Venus and Adonis, Dmitry Krymov’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (As You Like It) and the RSC’s A Tender Thing. Spread throughout the book, I’m pleased that I’m […]