March 14, 2012, by Peter Kirwan

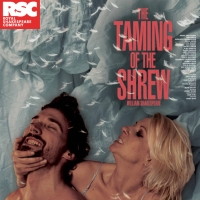

The Taming of the Shrew (RSC) @ Nottingham Theatre Royal

Writing about web page http://www.rsc.org.uk/whats-on/the-taming-of-the-shrew/

The Taming of the Shrew carries a great deal of baggage with it. The gender politics that are inevitably foregrounded in production (is this inevitable? Are there other issues that are being obscured?) are read through the identity of the director, through our own filters of acceptable behaviour, and through our conflicted desires to enjoy a comedy and condone misogyny. In recent years, as in the last RSC production and that of Propeller, the tendency has been to ramp up the comedy of the play as far as possible, either to subvert it through unexpectedly dark moments or to turn the whole play into an openly performative satire of extreme behaviours on both sides. Lucy Bailey’s touring production for the RSC fell squarely into this latter character, with an exhaustingly energetic romp that nonetheless provoked some difficult questions.

This Shrew functioned as extended foreplay, with emphasis on the "play". The entire set was an enormous bed, raking sharply up towards the enormous headboard, and made up with sheets. Pillows became playful weapons, wielded with varying levels of frustration or humour, and characters romped under the sheets. The intent was clear – sex was always the ultimate end point of this production, and everything that led up to it was negotiation.

The long Induction introduced Nick Holder’s repulsive Sly, an enormous and bedraggled drunkard who farted, belched and gurned his way around the stage. In the opening, he was turfed out of an offstage bar by Janet Fullerlove’s Marian Hacket, who became a semi-demonic figure, snarling like a dog and savaging the prostrate drunkard in a bizarre dream sequence. When Sly was awoken by the lords and persuaded that he was, himself, a lord, he refused to take on any decorum, simply stuffing the fine foods into his mouth and barking gleeful orders. The wonderful Hiran Abeysekera played Bartholomew, and was genuinely entertaining, revelling in the teasing aspects of his role as Sly’s ‘Wife’, but then panicking quietly as the rest of the lords ran off to leave them alone. His attempts to flee the stage were rebuffed by attendants who threw him bodily back on, and it was left to Bartholomew’s wits to ensure that Sly – already limbering up for what would perhaps be an overambitious exertion – kept his clothes on.

The two settled to watch a play, which was delivered for most of the first half as much to the onstage audience as to the Nottingham crowd. In between scenes, Sly and Bartholomew engaged in extended bedplay, getting under the sheets and playing chase games beneath them, usually ending in Sly losing his pants, being confronted by the demonic Hostess, or being denied his pillows, before resuming his seat. Sly’s spectatorship translated into a preoccupation with watching and being watched throughout the play, and our complicity in what we watch. As Kate and Bianca fought with pillows, a leering Sly jumped up and joined in. As Petruchio’s servants gathered, a pants-less Sly ran about the stage cackling, covering his genitals with a handy saucepan. This onstage audience slowly disappeared though, Sly becoming invisible by the play’s second half, apart from a brief appearance when he ran across the stage drunkenly repeating "I’m a lord!" The gradual loss of the onstage audience perhaps indicated an intent to slip into a simpler relationship with the play world, at the cost of the critical awareness that the dual frame offered.

Spectatorship also informed the main play’s opening, as Lisa Dillon’s Kate was paraded in to slow folk music and a cackling audience. The production was roughly set in rural Italy of the 1940s, but the misogynist parade enacted here was perhaps more reminiscent of Tudor England – a woman led by a rope, neck and wrists encased in a shrew’s fiddle. Assembled townspeople jeered at Kate, who humbly accepted her torment. As she was released, however, she knelt on the floor, and then punched her gaoler hard in the crotch. She then single-handedly proceeded to take on the entire town: throttling, punching, kicking and throwing the men, who both railed and laughed at her, turning her rage into the equivalent of a bear-baiting. Sly, predictably, whistled and clapped along. The fight ended, however, with her exhausted and seated, burned out by her activity.

Dillon’s Kate aimed to shock in everything she did. Smoking and drinking hard throughout the play, mooning onlookers and utilising casual violence were only some of the more obvious tricks in her arsenal. More interesting was her aggressive sexuality, which she used to embarrass the men around her as she mimed masturbation on the floor or pulled a petrified Hortensio towards her. Kate was intent on doing everything that this patriarchal society disapproved of her doing; yet it was carried out with an air bordering on the desperate, her isolation becoming apparent in the moments of quiet when she ran out of energy. Her mocking mimicry of Elizabeth Cadwallader’s hypocritical whining Bianca was spot-on (particularly as Bianca stuck up fingers at her when Baptista looked the other way), but implied also Kate’s awareness of her own isolation and lack of acceptance.

David Caves was another troubled soul. Petruchio was cast deliberately tall and young, the actor physically imposing (and clearly strong) but also without the restraint learned through experience. He and the tiny Grumio (Simon Gregor) adopted a "Basil and Manuel" relationship, the taller man slapping his diminutive servant over the head while the servant ran chaotically about the stage. The two were both hard drinkers, travellers with few social mores. Their appearance in the farcicial wedding sequence gave perhaps the best representation of their libertine lifestyle – arriving drunk, topless and tattooed, Grumio with an enormous phallus in his longjohns and Petruchio bellowing loudly, the two looked like the last men standing on a student rugby team’s night out.

The dynamic between Petruchio and Kate was fascinating from the word go. Deeply sexually attracted to one another, the two engaged in a physical and verbal sparring contest cast explicitly as foreplay. Kate pulled out her usual tricks, and was shocked when Petruchio refused to back down. I would have liked to see a little more critique here, as there was something deeply troubling about watching a woman’s means of establishing power stripped away from her through his physical presence, but by and large it worked effectively as a means of casting their struggle. As he refused to back down, she resorted to more extreme means. She realised she had made a mistake as soon as she slapped him, the mood turning dark for a moment as his voice dropped. Shortly after, however, she attempted to disgust him even further by lifting her skirt and peeing openly on the bedsheets. Again, he stood and accepted it. If reading generously, the production seemed to suggest the power of a connection where one partner accepts the other unconditionally; however, the commercial framing still served to cast this within a framework of male economic privilege.

When moved to Petruchio’s country house, the taming became more traditional, and also perhaps more problematic. After being denied food, Kate paused, and then began scrabbing at Petruchio’s pants, driven by a sexual hunger in place of her appetite. Kate’s sexuality had been foregrounded throughout, but to have her driven so apparently compulsively towards sex with her torturer appeared to imply that, in fact, all she really needed was a good shag. The fact that Petruchio then denied her what she wanted was perhaps intended to prove to the audience that he wouldn’t take advantage of her; but equally served once more to deny her agency or expression. This was the most problematic aspect of the taming, and concerned me for the implication that female sexuality was part of what needed to be brought under control during the taming.

Among the rest of the cast were several highlights. Sam Swainsbury was wonderfully dapper as Hortensio, putting down a napkin every time he sat on the floor and reacting with horror to dirt and disorder. In disguise as the French music tutor, he was all arms, legs and drawling sufferance. Huss Garbiya also had a great impact as Biondello, a particularly simple servant with an energetic approach to the role. Bianca and Gavin Fowler’s Lucentio, meanwhile, served to parody the main plot with an appeal towards sentimental stereotyping (prancing together offstage, walking arm in arm etc.) which was undercut with glimpses of the two rutting unceremoniously behind shutters as Hortensio finally surrendered his claim.

Bailey’s productions have a habit of showcasing the follies of male behaviour (despite the fact that these follies are themselves perpetuated primarily on stage rather than in any other medium), and this production was no exception. The casual slapstick violence and drunken sexuality of the male characters remained at one level for most of the production, with very little variation, making this an exhausting and sometimes monotonous watch – as funny as it was, variety of tone would have been preferable, particularly in the second act where there seemed to be very little by way of development. However, when the male parody worked, it was extremely amusing – John Marquez’s affected Mediterranean Tranio and David Rintoul’s old school military man Gremio played their financial contest with increasingly exaggerated references to their own genitalia, physically turning the money comparisons into a battle that could only be resolved with a ruler.

The proof of Shrew inevitably comes in Kate’s final speech, and this was where the production had failed to adequately lay ground, the scenes of her taming remaining at too consistent a level of gruding compliance, until the kiss in the street where the two seemed finally to connect. The final speech was delivered with initial frustration but growing passion, played as a paeon to compromise and sociability. It ended with her appealing to Petruchio and kneeling before him. He stood, taken aback, and then knelt in turn before her, kissing her feet, in a pleasing gesture towards reciprocity. The two then began frantically tearing off their clothes and ran upstage to get under the sheets and finally consummate their marriage. The journey may have been problematic, but the conclusion rang true, casting the play as the necessary process of groundwork for an energetic and equal relationship. The return to the Sly frame added little to the play, as Sly was returned to the open and had money scattered over him for the Hostess to subsequently come across him. However, this was largely an energetic and amusing Shrew that made a strong stab at finding both comedy and a sense of equality in its resolution.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply