January 22, 2012, by Peter Kirwan

Coriolanus @ The Broadway Cinema, Nottingham

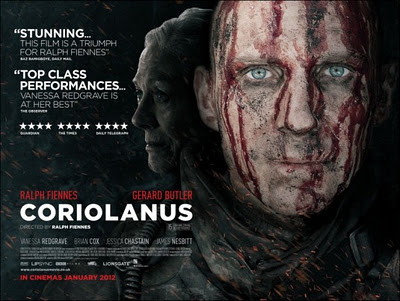

The best thing about the poster for Ralph Fiennes’s new film of Coriolanus (and his directorial debut) is the contrast between the streams of red blood and those ice-cold eyes. In a single image we see the entire film – a steady, chilling gaze framed by horrific images and the messy reality of war.

For those of us who saw it, it’s impossible to avoid comparisons with Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s Roman Tragedies, which similarly updated Coriolanus to the boardrooms and corridors of power, and turned the play into a critique of media involvement in politics and the machinations of state. Fiennes’s movie takes the concept but integrates it deeply into a setting that evokes the Yugoslav wars and Arab Spring (fortuitously, as filming had been mostly completed by the middle of last year). The blurring between the fictional world of "A Place Calling Itself Rome" and the real world was most apparent in the appearance of Jon Snow, reporting from the comfortable sofas of the Fidelius News network and grilling guests about the political ambitions of Caius Martius.

Televisions featured throughout, from the opening speeches of Menenius listened to by a fuming protest cell to the carefully staged presentation of Martius to the consulate. In the marketplace, surrounded by Eastern European stallkeepers, Martius blinked in the glare of a dozen cameraphones; and a microphone damningly picked up his hissed complaints to Brian Cox’s Menenius in the senate room. For his final aborted apology, senators James Nesbitt and Paul Jesson convened a tacky TV studio set-up, and riled up the crowds to call for his banishment with chants of "It shall be so!" More movingly, Virgilia (an excellent Jessica Chastain) twitched uncomfortably in front of lagging news reports of the fighting in Corioles while her son heedlessly shot cans with an airgun outside.

Fiennes’s Martius was ill at ease in this constantly recorded world. In the opening sequence, a mob waving protest banners advanced on Rome’s central grain store, and he faced down protesters while snarling at the watching cameras, which kept rolling as the riot police advanced. The messiness of adhoc recording translated to the excellent camerawork, particularly as Martius lashed out at the tribunes, pushing one to the floor while police attempted to keep a roaring mob at bay. In the chaos, the camera came detached, focusing on details – an eye, a phone, a hand, a slogan – as Menenius finally lost control of the situation.

The gritty feel showcased a stunning environment. As a grizzled Martius left Rome for banishment, he marched through wartorn ruins and bleak countryside, a world of roads that stretched to nowhere and roaming wild dogs. Yet emerging at Antium, a Mediterranean coastal town, we saw the peaceful beauty of the country desolated elsewhere by fighting. The soldiers of both armies were rowdy skinheads, tattooing each other and drinking to their respective iconic leaders. As unthinking as the masses incited by the tribunes, the soldiers were fiercely loyal to whoever commanded them, transferring as easily to Coriolanus as they did back to Lartius in the final moments.

The war scenes were expertly shot, making good sense of the text as Martius ran off alone after an explosion to wreak havoc. A shocking sequence saw him touring a burnt out apartment block, kicking down doors (a nod was made here to the old man who gave Shakespeare’s hero assistance, as one elderly man offered a bottle of water from his sofa) and shooting civilians, whose bodies we were reminded of throughout. Aufidius (Gerard Butler) himself found the bodies of his wife and children left bleeding in a car following the fall of Corioles. Yet while this was a war conducted primarily with bombs and guns, the cultish followings of both leaders allowed them to strip themselves of their heavy weaponry when finally meeting and engage in a knife fight, the two holding each other in a death embrace that found more intimacy than anything else in this cold environment.

Crucially, Fiennes only laughed in the company of his soldiers. With his mother, the excellent Vanessa Redgrave, he could only humble himself, occasionally crying out in frustration at the constricting nature of their relationship. Yet Virgilia and Volumnia made an impressive team, whether tussling with the tribunes after Martius’s banishment or kneeling together before Martius’s army. In an extended and fantastically played scene, Virgilia’s steady gaze and Volumnia’s no-nonsense appeals finally reduced the soldier to tears, helped by a genuinely surprising intervention from his otherwise silent son. Yet even more moving was Cox’s Menenius, tasked with the impossible. Facing Martius at night, he was stunned to be cut off by his former friend, and looked around the rest of the Volscian army before leaving, silently. In a short sequence following, he sat by a canal and took of his watch. Quietly, he slit his wrist and bled to death, another neglected body lying alone at the side of the road.

There was great support from John Kani as Cominius and a fine group of morally ambivalent rebels, but this was ultimately Fiennes and Butler’s show. As Aufidius shaved Martius’s head, his hand lingered on his skull, reminding us of his deeply conflicted relationship with his new ally. Fittingly, the final scene played out not in the Volscian camp, but at a roadside checkpoint. Surrounded by Aufidius’s men, Martius killed two before finally falling into Aufidius’s arms. As the latter’s dagger slipped into Martius, the two men embraced more tightly than ever before, lowering themselves together to the ground. There was no final eulogy or second thought from Aufidius – just the final image of Coriolanus’s body, thrown onto a bare platform. This was raw, gripping Shakespeare for the twenty-first century, and an impressive turn from Fiennes both in front of and behind the camera.

It’s a truly wonderful film that more than compensates for last year’s patchy Tempest.

My favourite sequence was when the film cut from Coriolanus lying shells-shocked on the ground after the bus blew up to his home, where Volumnia eventually worked herself up into a tirade about her son’s braveness. The picture then cut back to Coriolanus on the ground, who roused himself and started to shout at his men, but the sound continued with the voice of Volumnia, overlaying their two speeches. This seemed to imply that Coriolanus’s bravery and resolve was something his mother had instilled in him. A crucial point that makes sense of the film’s conclusion when the withdrawal of his mother’s approval has such a devastating impact on his determination to press home his attack on Rome.