July 18, 2011, by Peter Kirwan

Doctor Faustus @ Shakespeare’s Globe

Writing about web page http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/theatre/on-stage/doctor-faustus

The Globe’s summer season this year is surprisingly light on Shakespeare. The only two main house Shakespeares are All’s Well and Much Ado about Nothing, as well as touring versions of Hamlet and As You Like It, but a surprising proportion of the season has been new writing and, celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Authorised version, Biblical plays. In addition, there has been the Globe’s first major revival of Marlowe’s Faustus, a too-rare outing for one of the Elizabethan era’s foundational plays.

Matthew Dunster’s production (based primarily, but not exclusively, on the B-text) didn’t dial down on the opportunity for spectacle. The first appearance of Mephistopholes was as an enormous skeletal animal head, which broke apart on Faustus’s command to reveal the "human" incarnation of the demon as Arthur Darvill. Fire flared from magic books, huge spirits strode about the stage on stilts, slickly-choreographed magic saw antlers and animal heads appear as if from nowhere and angels clashed with swords. Magic gives licence to imagination, and Dunster balanced the special effects with clever use of actors’ bodies for major set pieces. Thus, the Seven Deadly Sins emerged one by one from a trapdoor, each neatly characterised, and the forerunners helped act out their fellows’ particular vices, whether rolling the barrel-shaped Gluttony along the stage or creating a luxurious and fondling bed for Lust.

Paul Hilton’s Faustus held the stage throughout without dominating. His witty Faustus was quick and intelligent, but almost wilfully belligerent. His scorn for the idea of hell was absolute, and he laughed openly at Mephistopholes until, on two occasions, Mephistopholes touched him. The touch was significant – Darvill’s young demon always defaulted to a deferential, still position at some move from Faustus. When he touched him, however, Faustus screamed in pain, falling to his knees as the familiar spoke of the terrors of hell. While these moments left Faustus cowering, they had no lasting impact, and Faustus quickly returned to his confident self.

The relationship between the two was finely realised. They shared a clear bond that manifested in laughter and camaraderie when, for example, torturing Nigel Cooke’s Pope. Mephistopholes became Faustus’s audience of one, and it seemed for much of the production that the conjurer was attempting to impress the demon as much as use him. This naivety was, of course, part of his downfall, and was contrasted nicely with Darvill’s open scorn and obvious manipulation. While being a long way from "bromance", Dunster realised that the play’s main conflict lends itself ideally to a struggle of individuals, and Darvill’s quiet manipulations and amiable encouragement were a joy to watch.

For thematic purposes, Dunster’s production insisted on casting the human Faustus and the human(ish) Mephistopholes against a character of deliberately symbolic figures. A supporting chorus of actors wore dark glasses and carried magic books, creating sound and visual effects and acting to represent Faustus’s art in a corporeal sense. They interacted freely with named characters such as Lucifer and Beelzebub, and remained onstage for most of the play in order to pull Faustus towards his inevitable end. In the final reckoning, they appeared with hand-held puppets, trilling and cooing as they pulled Faustus into hell.

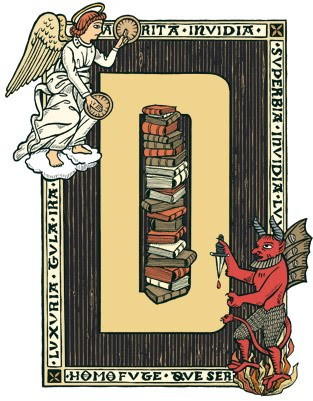

The leads were ably supported by a strong supporting cast, with a couple of exceptions. The Good Angel and Bad Angel, who appeared swinging swords at one another – the one with white wings and halo, the other with horns and broadsword – were not quite stylised enough to convince as allegory, but were unnatural enough to be realised as characters, and instead looked and sounded false. Much better were Nigel Cooke’s goat-legged Lucifer, who supported himself between two minions, and Chinna Wodu’s terrifically-imposing Beelzebub, who lashed a whip at the Deadly Sins and held Pride aloft on his shoulders.

The strong cast helped tie together the episodic and potentially repetitive plot. William Mannering’s Benvolio, for example, was exuberant and outrageously scornful, until he found the horns on his head and began furiously screaming at Faustus. Michael Camp and Jade Williams were both lecherous as the Duke and Duchess, and the heavily-pregnant and insatiable Duchess openly flirted with Faustus, becoming aroused by the grapes that Faustus fed her and pulling him to the back of the stage, with the full approval of her husband. Cooke’s Pope was another standout, combining sanctimonious preaching with harsh cruelty in his treatment of Jonathan Cullen’s Bruno. The Chorus came into its own again during the exorcism scene, where the gradual tormenting by the invisible Faustus and Mephistopholes eventually saw them throw up their instruments in terror and flee.

The comic characters were also genuinely funny, particularly Pearce Quigley as an older Robin, whose deadpan humour repeatedly brought the house down. Richard Clews as Dick was a more straightforwardly foolish clown, with a huge crush on the pantomime dame Nan Spit, played by a cooing Robert Goodale. Cooke played a phlegmatic Horse Courser who stripped down to his long johns in fury after losing his horse, and even Iris Roberts’s Hostess entertained in the slight goblet scene. The attention given to minor characters was pleasing throughout: Beatriz Romilly played a demure and retiring Duke’s Servant who, when asked to inquire as to who the mob attempting to get in were, tremulously made her way to the edge of the stage, before unexpectedly screaming her challenge in a terrifying voice and drawing a pair of pistols. The action was held together with a compelling performance by Felix Scott, who played a matter-of-fact Wagner who was also the Chorus, commenting sadly but soberly on his master’s fate.

The chaos was entertaining, but the purpose of this was to make the quiet moments more effective. As the two Cardinals who had been replaced by Faustus and Mephistopholes were dragged offstage (the same actors had played both the Cardinals and the "fake" versions), Faustus turned with a troubled face to Mephistopholes and saw his companion fully enjoying their fate. In a similar pause with a very different tone, Faustus stood in quiet awe as the human Helen of Troy emerged from a multi-bodied iconic rendering of her, gazing in delight at her beauty. This moment was particularly effective when contrasted with the earlier appearance of the demonic courtesan, who even had a sparkler fizzing in front of her crotch.

This inventive production’s strength was in providing an entertaining and colourful background which served to enhance, rather than distract from, the central dialogue between Faustus and Mephistopholes. Faustus’s appeals to the crowd, his self-justifications, his belligerent delusions and his mounting terror were generally well-realised, and while I would have liked the final death to carry more weight (and not to have been followed by the worst jig I’ve ever seen at the Globe, a dull, ugly and unfunny macabre dance of the puppet demons), the production had done its job. The final image to take away was the sight of Darvill’s Mephistopholes crowing over his prey, joyfully admitting his intentions in a combination of victory and frustration – for this Mephistopholes had never made a secret of his evil.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply