September 9, 2012, by Stephen Mumford

Metaphysics and Better Physics

Last week I attended a workshop on Causation in Physics, part of a larger project called Causation in Science (CauSci for short). Among the speakers was the ever-eloquent and erudite Thor Sandmel whose talk raised the question of how physics relates to our experience of causation in the world. We have a philosophical theory of what it is for one thing to cause another but is it superseded by the claims of physics?

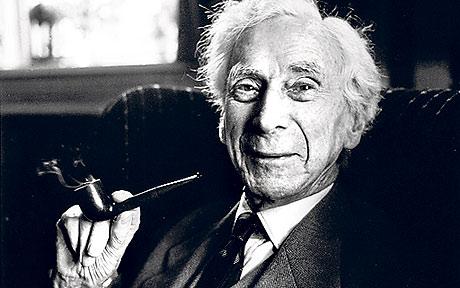

I recalled again Bertrand Russell’s old attack on the philosophical approach in his famous 1913 paper ‘On the Notion of Cause’. Our regular pre-theoretical understanding of the world has it that causing involves an asymmetry. Causes produce their effects rather than vice versa. An impact from a brick makes a window smash, for instance: it is not the smashing of the glass causing the brick to hit it. And light shining on a plant causes it to grow; the plant’s growth doesn’t make the sun shine. But Russell noted that physics had eliminated the asymmetry that was essential to this popular conception of cause. Instead, the language of physics was a language of equations (F=ma, F=Gm1m2/d2, and so on). And the thing about equations is that they can be read either way: from left to right or from right to left. In other words, physics described a world in which all was symmetrical and, while we were used to processes that ran from A to B, in theory they could just as well run from B to A. So much for causation.

Russell was perhaps the first in a long line of scientifically informed philosophers to suggest that philosophy had best leave the description of reality to science. Where metaphysics and physics came into conflict, we should always give way to the physicists. They were the experts. And physicists have themselves been happy to join in this attempted erosion of philosophy’s domain. Stephen Hawking, Lawrence Krauss, and even our beloved Professor Brian Cox have all recently proclaimed the end of philosophy or questioned whether it says anything useful at all.

During Sandmel’s stimulating talk, however, for the first time I realised that there was no reason at all why a metaphysician should run scared from Russell’s attack. Much of physics consists in the construction of a mathematical model of reality. But the world is not a number: not a function, nor an equation. Physics is an attempt to describe reality in largely mathematical terms but we should not mistake the description for the reality. Mathematics provides a structure and there must be something concrete in which it is realised, otherwise we are living as a collection of mere abstract entities. If there is a clash between our philosophical grasp of the world and its description in physics it doesn’t automatically follow that the philosophers should roll over for physics and submit meekly to its authority. Where the mathematical modelling of physics fails to account for a core experience and conception we have of the world, sometimes we should demand a better physics.

Russell’s interpretation of physics can of course be contested. Even where an equation adequately describes some real situation, intervention to change one value (and thereby the others) remains a possibility. That looks like asymmetry – and intervention sounds like causation. It is worth noting further that the truths of cutting-edge physics can be just as debated and speculative as any in philosophy. There are already well-known attempts to reintroduce asymmetry back into the field: in information theory and with the notion of entropy, for instance.

Philosophy doesn’t provide everything we need to describe the world. We also need the evidence of our senses. But philosophy has a role. A complete understanding would include both of the facts of experience and the general sort of metaphysical thinking provided by the philosopher, for there are some questions that unaided science simply cannot answer.

For an introduction to metaphysics, see here: shameless plug

For more on Russell’s own metaphysics, see here: and again!

Great, Stephen. It seems to me that issues of phenomenology are most salient in relation to knowledge-claims (philosophical or scientific) concerning human beings qua sentient beings. When it comes to vindicating the concept of causation, it would seem most important to know whether or not even the purely physical world is irreducibly qualitative and/or inherently asymmetrical. Also, since the answer looks patently to be yes at the macro level, it would seem that there is no way even to defend a no answer without also rejecting emergence in favor of metaphysical or ontological reductivism — the doing of which appears in turn to be at least philosophically tainted, if not philosophical in entirety.

Brilliant post! Philosophy should never roll over for science and all science is full of metaphysical assumptions. Especially physics. The philosopher of physics’ job is to bring these assumptions out in the open and debate them.

I’d suggest that while Russell is representative of 20th century advocates of science over philosophy, the issue goes back as far as the 17th century. The success of Newton’s empirico-mathematical treatment of nature and his voiced opposition to hypotheses lead to an increasing number of thinkers putting forward empirical evidence to settle philosophical arguments. That Newton was mostly silent about the mechanical metaphysics which underlaid his project, and that the theological arguments which he made are philosophically weak did little to dent the excitement caused by his work or limit the profound change in our understanding of what our knowledge of the natural world could be.

Thanks for a really interesting post.

it is very interesting, must be great one as it is by Russell…But equations are as good as above topic.”Action equal to the results obtained by the cause” which has a definite physical meaning in real nature and human senses as well. But

to assume our self as causes equals the action will loose the sense of actual real world phenomenon. it is like establishing physical laws under the influence of existing physical laws..very much interesting

Well said. I am very sympathetic with most of the views expressed in this post. On a related note, I am always struck by some of the outlandish accusations that are brought forth against philosophy by eminent scientists like Weinberg, Hawking, Krauss, etc. The claim that philosophy is dead, or that philosophy is irrelevant to science is patently absurd upon even a cursory inspection of the literature. To cite one example, in Hugget and Callender’s volume “Physics Meets Philosophy at the Planck Scale: Contemporary Theories in Quantum Gravity,” (2001) the ratio of physicists to philosophers featured is about 1:1, and some of the papers are co-authored by both philosophers and physicists. So, clearly there is work to be done with respect to the philosophical questions raised by modern physics, and moreover, it is being done by both philosophers and physicists alike. All in all, I conjecture that the conflict is largely fabricated by some very loud, and albeit, prominent voices on one side of the fence. Even so, perhaps the unfounded allegations of Hawking, et. al. will inspire philosophers to reflect more on the relationship between philosophy and science, what it is, and perhaps what it should be. I for one think this is a very interesting question!

Well said. I am very sympathetic with most of the views expressed in this post. On a related note, I am always struck by some of the outlandish accusations that are brought forth against philosophy by eminent scientists like Weinberg, Hawking, Krauss, etc. The claim that philosophy is dead, or that philosophy is irrelevant to science is patently absurd upon even a cursory inspection of the literature. To cite one example, in Hugget and Callender’s volume “Physics Meets Philosophy at the Planck Scale: Contemporary Theories in Quantum Gravity,” (2001) the ratio of physicists to philosophers featured is about 1:1, and some of the papers are co-authored by both philosophers and physicists. So, clearly there is work to be done with respect to the philosophical questions raised by modern physics, and moreover, it is being done by both philosophers and physicists alike. All in all, I conjecture that the conflict is largely fabricated by some very loud, and albeit, prominent voices on one side of the fence. Even so, perhaps the unfounded allegations of Hawking, et. al. will inspire philosophers to reflect more on the relationship between philosophy and science, what it is, and perhaps what it should be. I for one think this is a very interesting question!

[…] Stephen Mumford. Are philosophical theories of causation superseded by theories in the natural sciences? Ans: No. […]

Nice post Stephen, which makes me wondering: why do we say that equations are symmetric? Surely, the = sign is a symmetric sign but, leaving aside the intervention approach you recalled, we must consider that there is a hidden epistemic asymmetry in any equation: one part of it is considered the “solution” to the problem raised by the other part! “4” is the solution to “2+2”. Equation establish a metaphysical identity based on an epistemic asymmetry. Perhaps this has to do with time as well: we hit the problem before the solution. Causation without time is symmetric, but this is a classical and huge problems. So, philosophy should keep going and science should keep listening!

OK, so let me try this in a few more words than my fairly flippant response on Twitter allowed. The question that was asked there was whether philosophers should have a place at the table where the “final theory” is thrashed out, to which my response was that they would be more useful making the tea. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this provocative comment led to a torrent of unpleasantness, but actually it almost entirely missed the point I was trying to make.

Of course I understand that philosophy underlies everything I do in science, even if my everyday approach is what philosophers of science may well dismiss as an overly-simplistic doctrine. The most basic tenet of most scientists, Occam’s Razor, is undeniably a very simple, very effective, philosophical principle. So of course I make no bones about the fact that philosophy is a vital underpinning of science. This seems such an obvious point that I did not tweet it (even though it is simple enough that it can fit into 140 characters!), and I think that few if any scientists would dispute it. It is interesting that those responding through Twitter seemed to think that the fact that scientists don’t acknowledge this point all the time indicates that we dismiss philosophy as a waste of time, which perhaps more accurately indicates the fact that they don’t very often bother to ask us, or, indeed, interact with us in any way.

But that wasn’t the question. The question was whether philosophers should have a seat at the table when the “final theory” is being thrashed out. The point I was trying to make in my hamfisted way was that by then you work needs to be done. Just as Shakespeare needed the rules of grammar and the conventions of storytelling to be established before he could produce great literature, so scientists need the language of mathematics and the conventions of philosophy to tell them how to proceed. This is not in any way to deprecate mathematicians or philosophers; in fact the necessity of what they contribute underlines the fact that they are the key players. It just means that they are not the final stage of the process, and if their work is not complete before we get to this hypothetical final negotiation, we will end up unable to complete the theory.

Let me illustrate with one historical example: there have always been intense philosophical discussions about the nature of quantum mechanics. Until the mid-twentieth century, the idea of hidden variables — that there was an underlying deterministic theory that we just didn’t understand yet — stood alongside other philosophical interpretations, and, indeed, had such powerful exponents as Einstein. Developing and comparing these various possibilities is undeniably in the realm of philosophy, and a vital step toward understanding the way the Universe works, but philosophy had no way to decide which, if any, should form part of the “final theory” of the way the Universe actually works. That required a very smart theoretical physicist, John Stewart Bell, to come along and point out that the hidden variable theory made definite predictions that were different from the other philosophical explanations, and very clever experimental physicists to then carry out the test and show that the way the Universe behaves is not consistent with the local hidden variable explanation.

And before any irritated philosophers jump down my throat again and point out that this inferrence relied on a philosophical approach, albeit one at least as old as Hume, let me reiterate that this is my point: philosophy is a vital underpinning of science. It is, however, not an equal partner since demonstrably it does different things. The fact remains that there was no way for philosophy to move us further forward in understanding the quantum mechanical Universe, and it required scientists to establish that one of the possibilities was not part of reality. In this illustration at least, the philosophers should step back from the table once their work is done and let the scientists do their part. And if you have sorted all the other prerequisites to that final theory, you will have some time on your hands so I really don’t see why you shouldn’t make the tea.

Interesting post Stephen. It’s funny that it sounds very much like an argument I would make for why science hasn’t dispensed with religion!

[…] Stephen Mumford: If there is a clash between our philosophical grasp of the world and its description in physics it doesn’t automatically follow that the philosophers should roll over for physics and submit meekly to its authority. Where the mathematical modelling of physics fails to account for a core experience and conception we have of the world, sometimes we should demand a better physics. […]

[…] Stephen Mumford: If there is a clash between our philosophical grasp of the world and its description in physics it doesn’t automatically follow that the philosophers should roll over for physics and submit meekly to its authority. Where the mathematical modelling of physics fails to account for a core experience and conception we have of the world, sometimes we should demand a better physics. […]