May 22, 2015, by Guest blog

Race and Rights: Black Soldiers Part 3

To mark the 150th anniversary of the ending of the American Civil War in 1865, James Brookes of the Centre for Research in Race and Rights analyses the visual culture of African American flags—regimental colours that expressed the black experience of war and of life in America itself. In the third of this four-part series, he looks at the 24th United States Colored Troops.

A Civil War regiment would typically carry two flags into battle, the national standard and the regimental colours. Amongst regiments of white Federal soldiers, the regimental colours were visual symbols of the state or home locality from which the men had volunteered. Regulations called for regimental colours to be dark blue, bearing the coat of arms of the U.S. and with a red scroll displaying the unit designation. However, the patriotic groups that made flags for departing volunteers complied with these regulations to differing degrees. Conversely, the United States Colored Troops, first formed in 1863, were not raised from such concentrated home communities as they were instead made up of less concentrated populations of free men of colour in Northern states, as well as runaway slaves and captured ‘contraband’ enslaved subjects.

USCT regiments were denied a level of affiliation to a particular state or community, unlike white volunteer regiments. The designation “United States Colored Troops” denies a level of affiliation to a particular state, and thus the regiments became representative of the entire African American population, whether free and enslaved. As a result, their regimental colours took on a visual symbolism that embodied various themes relating a full gamut of African American experiences in this period. These included the desire for full emancipation and equality, the attainment of citizenship, and, unsurprisingly, a lifelong, individual and collective determination to avenge the blood drawn from the slaveholder’s lash. Over 150 regiments of the USCT existed during the Civil War, composed of approximately 180,000 African Americans. The full spectrum of these unique banners of civil and militaristic self-representation holds much potential for interpreting the powerful ways in which black soldiers viewed their military service as a means to attain liberty, equality, and citizenship in the United States.

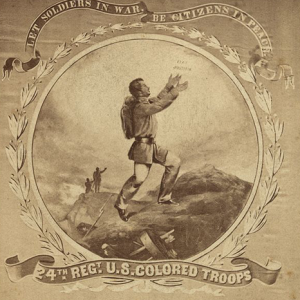

Image: David B. Bowser, “24th Regt. U.S. Colored Troops. Let Soldiers in War, Be Citizens in Peace,” photographic print on carte-de-visite, Courtesy Library of Congress.

The 24th USCT was largely composed of free black men from the eastern section of Pennsylvania and organised at Camp William Penn on the 17th February, 1865, two months before fighting would cease. Although many black soldiers enlisted in Colored Troops regiments in order to fight for African American’s right to citizenship in U.S. society, several enlistees in the 24th suggest different motivations. Two African-Canadian men, twenty-seven year old seaman James Robinson and nineteen year old waiter William E. Stratton were able to enlist at a time when financial bounties would be guaranteed for their service. They made $400 and $550 through local bounties respectively, and were each entitled to a $100 Federal bounty on completion of a year’s service. However, considering the risks of death and disease, as well as the potential for trial under the British Foreign Enlistment Act, it would be an unfair assessment to downplay the participation of these soldiers based solely on the motives for their enlistment.

Others gave a clear illustration of their desire to utilise military service as a means for social advancement. William Watkins, a five foot, five inches tall man, joined Company H of the 24th in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on March 6, 1865. Within ten days of his recruitment, Watkins was promoted to sergeant, an impressive feat for an African American during this period of discrimination, disenfranchisement, and systematic exclusion. The rank of sergeant required an ability to assert one’s authority over enlisted men, adhere to orders from commissioned officers, and to take responsibility for one’s company. Literacy was a necessity. Watkins would survive the war only to suffer from illnesses contracted during his service.

The regiment deployed to Camp Casey south of Washington, D.C. for garrison duty before proceeding to Point Lookout, Maryland, where it guarded imprisoned Confederate soldiers. Holding over 50,000 Rebel prisoners-of-war during the conflict, often in cramped, unsanitary conditions, Point Lookout had a notorious reputation. African-American troops “gained a new sense of their own place in society while guarding the captured Confederate soldiers, whose dejected demeanour and powerless situation contrasted markedly with former boasts of racial superiority and military invincibility.”

Some Confederate prisoners criticised the treatment they received from black prison guards, but whether they were explicitly referring to the 24th is unknown. Confederate veteran Charles T. Loehr recalled, “The guards consisted of negroes of the worst sort… [they] would often compel [prisoners] at the point of bayonet to… kneel and pray for Abe Lincoln, and forced them to submit to a variety of their brutal jokes, some of which decency would not permit me to mention.” Loehr’s statement raises issues regarding certain African-American’s management of prisoners-of-war. The subject is one fraught with a myriad of social and political implications, raising issues of prisoner treatment throughout the war, Confederate policies towards surrendering black soldiers, the level of training provided to black soldiers, and the reconciliatory reframing of the conflict in the late nineteenth century, amongst many others. The subject defies generalisation and deserves further consideration elsewhere.

Following the 24th’s prison duties at Point Lookout, the unit was assigned to the Roanoke region of Virginia, where it preserved order and distributed supplies to “needy inhabitants.” One can conceive of how destitute white southerners viewed the occupation of their territory by African Americans in Federal military uniform, when in the antebellum period slave patrols and white militias had held unchallenged sway.

David B. Bowser was commissioned to design USCT regimental banners during the Civil War. He was an African American artist who had also painted portraits of John Brown and Abraham Lincoln, thereby exhibiting his sympathies towards figures tied to the radical abolition movement. The colours of the 24th feature an image of an African American soldier atop a hill littered with the debris of battle with his hands raised in the air in a fashion extremely reminiscent of the enslaved African figure found on anti-slavery medallions in the 18th and 19th centuries, and including Josiah Wedgwood’s famous pendant. The slogan “Am I not a man and a brother?” that accompanied Wedgwood’s medallion of the chained bondsman begs the question of equality between whites and blacks. The flag of the 24th bears the script “Let soldiers in war, be citizens in peace.” The message “Fiat Justitia” which the soldier is reaching up to is a Latin phrase meaning “Let justice be done.” Frederick Douglass and other black abolitionists adopted this expression. It originates from a 1772 British legal case regarding slavery. The flag thus symbolises the desire of African American soldiers to have their military service appraised fairly by whites in a transformative process that would confirm their freedom and right to full citizenship with the war’s close and defy the enduring stranglehold of a white racist ideology.

The 24th USCT does not appear to have seen combat during the Civil War, but it would be wrong to assume it did not suffer casualties through illness, exposure, accidents, and attrition. Nevertheless, there were certainly men who cursed the lack of an opportunity to earn respect on the battlefield. Regiments could forge lasting legacies through combat and the 24th’s separation from the front lines of the war surely contributed to its peripheral place in Civil War history. Although the visual imagery on the regimental flag does not reflect the often mundane duties assigned to the 24th, the banner provides an insightful view into how African-Americans envisioned the significance of their military service. The 24th was used largely for auxiliary roles during the war but an army is not merely made up of its fighting soldiers. They performed important functions, notably in providing relief to newly-returned citizens to the United States whilst stationed in Roanoke, and should be considered fortunate for their absence from the gruelling, drawn-out combat of the last months of the Civil War.

James Brookes is an MRes student in the American and Canadian Studies department, where he is writing a dissertation on the visual culture of American Civil War soldiers. He begins his PhD in the department in September. He is a member of the postgraduate reading group at the Centre for Research in Race and Rights.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply