May 18, 2015, by Guest blog

Race and Rights: Black Soldiers Part 2

To mark the 150th anniversary of the ending of the American Civil War in 1865, James Brookes of the Centre for Research in Race and Rights analyses the visual culture of African American flags—regimental colours that expressed the black experience of war and of life in America itself. In the second of this four-part series, he looks at the 22nd United States Colored Troops.

A Civil War regiment would typically carry two flags into battle, the national standard and the regimental colours. Amongst regiments of white Federal soldiers, the regimental colours were visual symbols of the state or home locality from which the men had volunteered. Regulations called for regimental colours to be dark blue, bearing the coat of arms of the U.S. and with a red scroll displaying the unit designation. However, the patriotic groups that made flags for departing volunteers complied with these regulations to differing degrees. Conversely, the United States Colored Troops, first formed in 1863, were not raised from such concentrated home communities as they were instead made up of less concentrated populations of free men of colour in Northern states, as well as runaway slaves and captured ‘contraband’ enslaved subjects.

USCT regiments were denied a level of affiliation to a particular state or community, unlike white volunteer regiments. The designation “United States Colored Troops” denies a level of affiliation to a particular state, and thus the regiments became representative of the entire African American population, whether free and enslaved. As a result, their regimental colours took on a visual symbolism that embodied various themes relating a full gamut of African American experiences in this period. These included the desire for full emancipation and equality, the attainment of citizenship, and, unsurprisingly, a lifelong, individual and collective determination to avenge the blood drawn from the slaveholder’s lash. Over 150 regiments of the USCT existed during the Civil War, composed of approximately 180,000 African Americans. The full spectrum of these unique banners of civil and militaristic self-representation holds much potential for interpreting the powerful ways in which black soldiers viewed their military service as a means to attain liberty, equality, and citizenship in the United States.

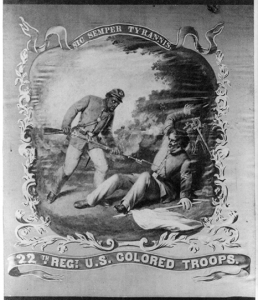

Image: David B. Bowser, “With Great Steadiness and Courage” – 22nd Regt. United States Colored Troops, photograph of regimental flag,” Courtesy Library of Congress.

The 22nd United States Colored Troops was organised at Camp William Penn between the 10th and 29th of January, 1864. Their white colonel was an experienced officer, Joseph Kiddoo. The narrative of the regiment illustrates the desire of many Black troops to shun the tedious manual labour that they often found thrust upon them and to embrace the opportunity to conduct themselves honourably on the battlefield, regardless of the cost: the right to bear arms is the right to humanity in the face of white supremacist ideology intent upon black dehumanisation.

The radical abolitionist and self-emancipated freedom-fighter Frederick Douglass encapsulated ideological beliefs held by the men of the USCT in a speech in Rochester, New York in 1863: “Who would be free themselves must strike the blow.” Those who enlisted were the “powerful black hand” of the imperilled nation, and he called upon them to “smite with death the power that would bury the government and your liberty in the same hopeless grave.” Military service offered African Americans the opportunity “to end in a day the bondage of centuries, and to rise in one bound from social degradation to the plane of common equality with all other varieties of men.” Proving their ability as soldiers was inextricably linked to the ongoing quest to prove that they deserved citizenship to a white U.S. nation intent on freedom for whites only.

Black regiments often formed two extremes of the Union Army’s operations. Repeatedly relegated to support roles as labourers and denied the right to bear arms, their fighting ability was doubted within a white national imaginary predicated on racist conceptions vis-à-vis black militancy. When finally employed in combat, they were in several instances engaged in the most dangerous areas of battle. They received little quarter from the enemy. An article in the Daily Richmond Enquirer following the Battle of the Crater of July 1864, in which many surrendering black soldiers were shot down by Confederate soldiers, illustrates the policy towards the USCT. “We regret to learn… some negroes were captured instead of being shot” the newspaper declared, “butcher every negro that Grant hurls against [our] brave troops and permit them not to soil their hands with the capture of one negro.”

The 22nd received orders at the end of January to move to the front. The regiment went into camp near Yorktown until spring and received drill instruction in manoeuvres and firing. However, for the first portion of their service their most prevalent instruments were shovels and picks. First posted at Wilson’s Wharf on the north side of the James River, the 22nd constructed earthworks. They repositioned to the south side of the James and once again found themselves employed in constructing defensive works. Here they also participated in the preparation of the Army of the Potomac’s crossing of the river on its arrival from the Wilderness Campaign.

In combat the 22nd gave a fine account of themselves, though often at a great cost. In June the 22nd led the charge of General “Baldy” Smith’s XVIII Corps offensive against the Confederate defences at Petersburg, taking 6 of the 7 artillery pieces captured by the 1st Division and 2 of the 4 forts. The Philadelphia Enquirer noted the regiment “lost a considerable number of men.” Charles R. Douglass, second son of Frederick Douglass, and a first sergeant in the 5th Massachusetts Dismounted Colored Cavalry, left an account of the Colored Troops in the fighting. For its actions the 22nd was “warmly commended at corps and army headquarters.” Colonel Kiddoo reported that “my regiment… behaved in such a manner as to give me great satisfaction and the fullest confidence in the fighting qualities of colored troops.”

At New Market Heights in September the 22nd served with the “most unflinching bravery” according to the report of Captain Albert Janes. The regiment repeatedly charged and scattered the enemy on the 29th and repulsed their counter-attacks on the 30th. Responding, the regiment “delivered a most daring and impetuous charge” against the strong works of the enemy, but was repelled. A month later the XVIII Corps struck the Richmond defences again. The black regiment once more led a charge with “great steadiness and courage” yet had to fall back. Lieutenant Colonel Ira Terry noted that some companies went to within a few yards of the enemy’s works. The 22nd’s casualties in killed and wounded exceeded 100, amongst them Colonel Kiddo, severely wounded.

The men of the 22nd proved themselves as well-ordered and efficient citizen-soldiers. As some of the first troops to enter the Confederate capitol of Richmond on April 3, 1865, the regiment “rendered important service in extinguishing the flames which were then raging.” General Godfrey Weitzel, commander of the all USCT XXV Corps to which the 22nd had transferred, selected the regiment to participate in the funeral ceremony of President Lincoln due to its “excellent discipline and good soldierly qualities”. The 22nd was involved in the efforts to capture John Wilkes Booth before proceeding in May to Texas where it garrisoned posts along the Rio Grande before mustering out of service on the 16th of October, 1865 in Philadelphia.

The regimental colours of the 22nd provide an example of a provocative piece of black visual culture. African-American David B. Bowser was a government-commissioned artist who designed several regimental flags during the Civil War. The colours of the 22nd featured strong abolitionist iconography and sentiment. The 22nd’s flag is unique in that it displays an African-American bayonetting a helpless white Confederate without mercy. Pro-slavery campaigners employed images wilfully endorsing white racist fantasies of uncontrolled black masculinity to heighten fears of emancipation held by whites. However, Bowser was an abolitionist who would paint John Brown’s portrait in 1865, and so was therefore not averse to aggressive policy in the fight against the slave-holding aristocracy. The white flag held by the prostrate Confederate could be a flag of surrender. The image would be a response to the atrocities committed in instances such as at Fort Pillow when southern troops refused to take black prisoners.

Another possibility views the flag as a symbol of southern whiteness. The second national flag of the Confederacy bore the Confederate battle flag on a field of white. The editor of the Savannah Morning News had linked the use of white on this flag to the “peculiar institution.” He noted: “we are fighting to maintain the… supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored races. A White Flag would be emblematic of our cause.” The 22nd’s flag also bears the motto Sic Semper Tyrannis (“Thus Always to Tyrants”). The flag appropriates the seal and motto of slave-holding Virginia. Employed in 1776 in defiance of British tyranny, it is utilised here by the black regiment to symbolise their own revolution against their white masters. It claims a semblance of the ideology of the Revolution that white northerners and southerners would attest to be the true heirs of throughout the conflict. The flag illustrates a yearning for entitlement to the benefits of republican citizenship through a revolutionary and turbulent trial.

The 22nd are notable for their ascension during the Civil War. From labourers employed in the construction of earthworks with the Army of the James, they rose to distinguished participation in the funeral ceremony of President Lincoln. The conduct of the soldiers received applause from the regimental to the corps level. Although it appears that their demeanour did not reflect the aggression implied on their regimental colours, the banner nevertheless attests to their determination in opposing tyranny in pursuit of liberty and the recognition of their worth as citizens.

James Brookes is an MRes student in the American and Canadian Studies department, where he is writing a dissertation on the visual culture of American Civil War soldiers. He begins his PhD in the department in September. He is a member of the postgraduate reading group at the Centre for Research in Race and Rights.

Image: David B. Bowser, “Sic Semper Tyrannis – 22nd Regt. United States Colored Troops, photograph of regimental flag,” Courtesy Library of Congress.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply