November 15, 2012, by Alan Sommerstein

From Mount Sinai to Michigan: the rediscovery of Menander’s Epitrepontes (part 1)

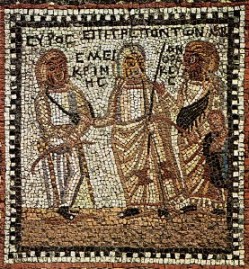

Menander’s comedy Epitrepontes (The Arbitration) is an exquisitely constructed drama in which a baby, reluctantly abandoned by his mother to preserve her reputation and her five-month-old marriage, is reunited with his parents by a process to which almost every character in the play makes an essential contribution (often an unintentional one). Virtue repeatedly earns its reward. The wife who remains loyal to a deserting and apparently philandering husband not only gets him back, but gets her baby back as well; the conscience-smitten husband, who resolves to return to her, learns a minute or two later that the child he had thought to be his bastard is actually his legitimate son and heir; the slave-prostitute whose ingenuity was crucial to the discovery of the truth is probably given her freedom; and the young man who was in love with her, but who gave up his hopes for the sake of his friend, wins her after all. And vice earns its punishment – though, this being a comedy, the punishment is not very severe. The man who tried to rob the baby of the few keepsakes that had been left with him – without which his father could never have been identified – is condemned and left with nothing; and the wife’s father, whose thoughts run always on the large dowry he gave with his daughter, and who thinks it gives him the right to control both her life and that of his son-in-law, ends up being defied by his own slave and humiliatingly lectured by someone else’s – though at the same time he is invited to “come inside and meet your grandson”, and that is only fair, since it was he, called in (in the scene from which the play takes its name) to arbitrate the baby’s fate when no one knew whose child it was, had seen that justice was done for it by awarding it to the couple who cared and not to the man who only thought of gain. Both in plot structure and in characterization it is arguably the best play of Menander that we have. It has long been thought to be one of his later works, and there is now some tantalizing evidence suggesting this is indeed the case; if so, one may well wonder – as Plutarch did, four centuries after Menander, when he compared the dramatist’s early works with his late ones – what Menander might have achieved in subsequent decades, had he not died (in a swimming accident, according to tradition) at the age of fifty-two.

I have said that Epitrepontes is “arguably the best play of Menander that we have”; but we don’t in fact have it – not anything like the whole of it, anyway. We don’t even know exactly how long it was; there are some scenes that are completely missing, and of others we have only tattered fragments, perhaps a few letters of each verse line. What we do have is enough to enable us to infer with fair confidence how the plot went, except perhaps in the opening scenes, and certainly enough to make it possible to patch together a script that can be, and has been, successfully performed. But much of this has come to our knowledge only recently – some of it so recently that the two latest editions, published in 2009 and 2010, are already out of date.

Menander seems to have been more widely read in antiquity than any other poet except Homer and Euripides, and Epitrepontes was one of his most popular plays. But while the Byzantine Empire had no Dark Ages as the West did, it did have a period – what one might call “the long eighth century” – during which little interest was taken in any form of literature that did not have either a practical or a theological value. During this period, almost the only ancient poets whose works were read, or – crucially – copied, were those who figured in the school curriculum. Menander was not one of these; or rather, all that was read in school under the name of Menander was a collection of sententious one-liners, most of which were not by Menander at all. We know what was happening to the real texts of Menander’s plays at this time: they were being treated as recyclable rubbish. There survive two or three manuscripts – what are called palimpsests – on which Menandrian texts were erased (though not completely) in this period and other texts, mostly of a religious nature, written on top of them (in one case the second text too has been erased and a third written on top of that). When interest in ancient literature revived in the ninth century, it appears that no texts of Menander were any longer available.

So for a thousand years nothing was known of Epitrepontes except for a few isolated passages quoted by various ancient authors. Then, in 1844, the German biblical scholar, Constantin von Tischendorf, came to St Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai – where fifteen years later he was to discover the famous Codex Sinaiticus of the Greek Bible – and found there, among other things, what we now know to be a leaf from a copy of Epitrepontes. But Tischendorf did not know that; he was only able to read one side of the leaf; and even that little bit of text (plus another bit from another play) was not destined to get into the public domain for another thirty-two years.

(To be continued)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply