January 26, 2016, by Stephen McKibbin

Notes from research leave: close encounters with the book

I’m currently on research leave completing a couple of projects. One of these is a new, student-focused edition of Doctor Faustus, and my leave allows me time to visit the archives necessary for editorial work.

We’re fortunate at Nottingham to have access to Early English Books Online (EEBO), a database containing thousands of scanned early books. A recent controversy when the Renaissance Society of America temporarily lost its access rights revealed just how essential this resource is, allowing scholars and students who otherwise couldn’t travel to archives to consult original materials.

The EEBO copy isn’t always perfect, though. Here’s a snippet from Faustus:

Doctor Faustus (London, 1604)

Doctor Faustus (London, 1604)

Bodleian Library STC (2nd ed.) 17429 (EEBO reproduction), sig. A2r

As you can see, the scan is faded and the words difficult to read. This is a tricky passage. Not only is the main text in the unfamiliar (to modern eyes) blackletter typeface, but we also have several lines of italicised Latin. I can, of course, refer to other modern editions to check my own transcription but, as a responsible editor, I’m going to head to Oxford’s Bodleian Library to consult their physical copy.

Pre-EEBO, editors of Renaissance plays who didn’t have expensive physical facsimiles would need to be in the archives from day one. I spent September at one such archive, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC, working on another play. This is a veritable church of Shakespeare scholarship, founded by a prodigious collector of rare Shakespeare books. The Folger provides short fellowships for scholars around the world to come and use its collections.

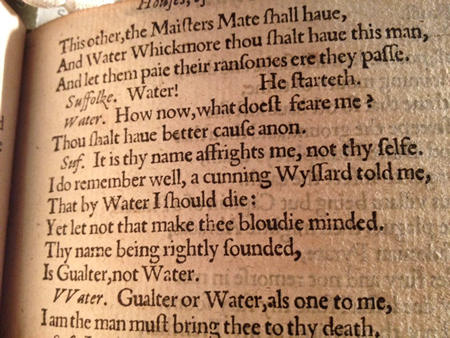

Working at the Folger and living one block away from the US Capitol (my picture above), is staggering in itself, but the difference it makes being able to work on physical books is extraordinary. Here’s one of the pictures I took, from an early version of Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 2. The book was published in 1594, so is over 420 years old:

The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster.

The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster.

Folger Shakespeare Library STC 26099, F2r

Working with physical books allows editors to see the words in context. This is a tiny book with thin paper (you can see the words on the next page bleeding through). The distinction between ‘W’ and ‘V V’ is stark on the yellowed page. But more importantly, I can see how the typesetters used the space of the page in relation to the physical book, sometimes cramming words together for space, sometimes creating blank space to emphasise important plot points. The physical book provides its own acts of interpretation that are much harder to see in photocopies.

Handling such a rare and old book is one of the thrills and privileges of being a scholar, but it’s an important reminder of the material, physical conditions that go into creating books, and which I’ll be bearing in mind as I continue editing Faustus.

Peter Kirwan

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply