November 24, 2015, by sdavies

Waltzing on Water

Guest post by Catherine Duigan and Sarah Davies (Aberystwyth University).

During extreme weather, a frozen lake can be a scientific, social and cultural event.

In temperate regions, like Wales in winter, frozen lakes are mainly seen in inaccessible relatively high altitude mountainous areas. Even here people pause to consider them; photograph them; paint them. They poke at the ice, peer through and estimate its thickness. The reckless test how much weight it can support. An extreme weather event will freeze the entire surface of mountain lakes and even the larger and relatively low altitude lakes, making it an even more remarkable and recorded incident.

In her early 1928 textbook on freshwater biology, Kathleen Carpenter (at Aberystwyth University) explained that it is one of the peculiar features of water that its maximum density occurs at a temperature of about 4°C, whereas the freezing point is 0°C. So when a body of water is sufficiently chilled, the heavier water, at about 4°C, tends to accumulate at the bottom, while the lighter water, at freezing point, forms ice at the surface. A persistent ice sheet also alters the thermodynamics of the underlying waterbody. Carpenter observed only long-continued freezing can solidify the whole mass, if it be beyond a few inches in depth, so that below the icy coating a body of free water is preserved in which life can still be maintained. She described how it is a common experience to see freshwater animals swimming actively beneath the surface of a frozen pond.

Kathleen Carpenter also defined stenothermic species which have a narrow range of temperatures which restrict their distribution. Wales has some well recognised low temperature stenothermic fish species, such as the Arctic Charr (Salvelinus alpinus) of Llyn Padarn and the Gwyniad (Coregonus lavaretus) of Llyn Tegid.

Visual records of frozen lakes

Historic ice fairs on frozen rivers have been recorded in well known paintings as part of our cultural heritage. Paintings by the Dutch Masters often included people skating on frozen canals and ponds as the popularity of the sport developed. The painting of Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch in Edinburgh, c. 1795 is a well-known and striking image. Such artistic representations provide insights into the severity of the weather conditions at a particular time, but also capture the cultural significance of these frozen landscapes. These extreme weather events were to be celebrated and commemorated.

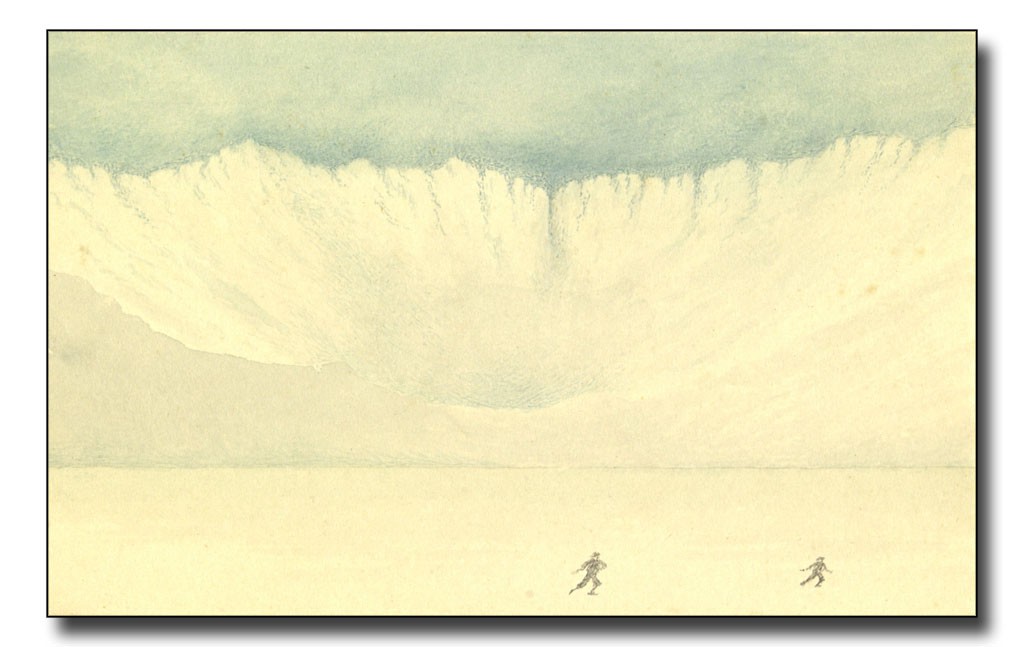

Llyn Idwal, by Frank Ward, date unknown (by permission of Llyfrygell Genedlaethol Cymru / National Library of Wales)

The recently discovered Lakes of Wales watercolour collection by Frank Ward includes a beautiful and remarkable image of Llyn Idwal frozen. The white lake and surrounding mountains are set against a glacier blue sky. And most intriguingly two small, well dressed and dynamic human figures are skating on the ice. Is the larger adult figure trying to catch up with the child?

Due to its location in Snowdonia, the surface of Llyn Idwal is known to freeze to a variable degree during cold winter weather. It does not freeze every year but it did this year (see photo above) and storms can break up the ice surface, with the wind creating piles of broken ice on the beach at the end of the lake.

But why was Frank Ward, a fisherman, motivated to record this particular Idwal freezing event in a painting? We do not know when this image was painted but a possible candidate is the winter of 1929, a particularly severe winter across northwest Europe, with reports of skating on other UK lakes.This ties in with the approximate timing of Ward’s visits to the area. During that year, Lake Windermere was frozen for many weeks with thousands of people out skating as late as March (Kington, 2010). In Ward’s painting, the lake and surroundings look like they have been frozen solid for a significant period of time. It is also tempting to conclude that there was a personal connection to the skaters as this is the only Ward painting which includes people.

Textual records of frozen lakes

Another freezing event at Llyn Idwal was reported in the Evening Express, January 8th 1908, describing the ‘ludicrous adventure’ of ‘Towzer’ Evans, a student from Bangor University College. ‘Towzer’ had gone up to Cwm Idwal to skate on the lake but fell through the ice. After clambering to safety, he then walked some distance to Bethesda to seek assistance. A lady from the village gave him a bed while she thawed his clothes, but overlooked his stockings. As he had to make a dash for the next train, she lent him an odd pair of hers. He was seen sprinting through the village in his knickerbockers, his legs ‘twinkling blue and green.’ ‘Towzer’ was reportedly entertaining his friends and the townsfolk of Bangor with the details of his escapade ‘with great relish.’

There are other newspaper reports of skating on Welsh lakes:

- The Llais Llafur noted on 10th February 1917 that Wales’ largest natural lake, Bala Lake (Llyn Tegid) was ‘frozen over for the first time in 22 years, and there is skating for miles along the lake. The farmers report serious losses among their flock.’ These icy conditions mean entertainment for many, but bring hardship to others.

- In January 1881, widespread freezing conditions were reported, with the River Taff frozen over at Llandaff and the Towy at Carmarthen. In this account, a weather-related death in Ludlow is juxtaposed with reports of skating on the ponds around Cardiff.

We have also found records of lake freezing in diaries, such as those kept by Richard Lister Venables (1809-1896) of Llysdinam Hall (Newbridge on Wye). From late November 1878, he recorded frost or snow most days, remarking on the thickness of ice that was forming on his pond. By 21st December, he noted that the river (Wye) was fit for skating. According to Dr Davies, who visited Llysdinam on 23rd December, special trains had been organised from Knighton to Llandrindod Wells so that people could enjoy the frozen lake there. He reported up to 200 people at a time on the ice, skating and playing hockey. By 29th December, the river was flowing again and a thaw had set in. The snow and ice had all gone by New Year’s Eve. (NLW A85/Llysdinam Estate Records).

These individual descriptions, similar to the paintings, provide snapshots of weather conditions, their impacts and cultural significance at a given time. The more continuous nature of diaries allow us to examine how prolonged such events were, the build up to them and their subsequent demise, whether gradual or a more sudden thaw. We don’t know of any systematic records of lake ice in Wales, but records extend back to 1936 for Lake Windermere. Lake ice phenology – the timing of the onset and duration of ice cover – can be tracked over years or decades. Such records can hold valuable clues about climatic variability, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (George, 2007).

We may think of frost fairs and skating on lakes here in the UK as a thing of the past, recent cold snaps such as in 2010 show that the tradition is very much alive, especially in Scotland. Although extremely cold winters are predicted to become less frequent in the UK as global temperatures continue their upward trend, they will of course still happen. Frozen lakes – picturesque, fascinating and of course dangerous – will continue to be memorable features of our experience of notable weather events in the UK.

The Snowscenes project on extreme winters and their impacts, was a forerunner to our current UK wide research on weather extremes. You can read more about Snowscenes here, including the fabulous composite images created by Alexander Hall, merging old winter scenes of the Lake District with the present day.

Do you have records or memories of lake freezing events in Wales or elsewhere in the UK? If so, please get in touch, we’d love to hear your stories!

References

George, D. G. (2007). The impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation on the development of ice on Lake Windermere. Climatic Change 81: 455-468.

Kington, J. (2010) Climate and Weather. Collins New Naturalist Library, Harper Collins, London.

Newspaper reports were obtained using Welsh Newspapers Online / Papurau Newydd Cymru Ar-Lein a fantastic, open access resource developed by the National Library of Wales / Llyfrygell Genedlaethol Cymru

Catherine and Sarah – thank you for putting together this post and for sharing some of your research materials. I know we have collected quite a few references to people skating on frozen lakes and rivers during the project and it would be good to collect them all together at some stage! In the meantime I thought I’d share a recent find from Herefordshire Record Office with you. Unfortunately I’ve not yet been able to confirm the location:

D6/1 – papers of Lady Elizabeth Coffin Greenly of Titley Court, Herefordshire

February 10, 1816 [Shipley ?]

Dear parents,

The frost is become very hard and we went to the great lake. First Susan, and then myself seated on a stool, were drawn by 2 skaiters. Mr Newdigate brought a chair he had constructed with boards on the top of what the colliers call a Corfe, a machine like a small sledge. On this the Gentlemen piled their great coats and seated thereon Susan and I were alternately drawn across the lake by the skaiters; it is a mile long.

I only wish Frank Ward had been there to capture the image!

Lucy.

In the 70’s and 80’s we would skate on a small lake (the Tarn) on Ilkley Moor. As I remember it, it would freeze hard most years and half the town would turn out to skate or slide. It was only a couple of feet deep so it would freeze more quickly than a big lake I suppose. My parents bought us ice skates, and they weren’t particularly well off, so it must have frozen regularly enough for that to be worthwhile. We would usually get a few days worth of skating each time.

One year the River Wharfe froze so hard that we all walked down it for some distance, but that wasn’t a normal event.

I don’t live there now so I don’t know if the Tarn freezes regularly now. I would be very surprised if it did.

Hi Kathryn, thanks for reading and for sharing your memories of frozen lakes and rivers. I’ll pass them on to Catherine and Sarah, Lucy.

Thanks very much for sharing your memories Kathryn, it’s very interesting to hear that this was a regular event during your childhood. We are picking up more and more references to skating on lakes and rivers, such as the note from Lucy above (thanks Lucy!). The most recent record we have been given for Welsh lakes is skating at Llyn Ogwen in Snowdonia in 2010 (thanks to Coed Celyn Hall, Betws-y-Coed). We have also learned about the great tradition of skating in the fens from Stewart Clarke (@fluitans) who sent us this link http://ousewashes.org.uk/ouse-news/exciting-fen-skating-film-launched-tomorrow-at-wwt-welney/

I’m fascinated by the sheer number of people who took the opportunity to skate when it was possible – we have a number of photos of crowded frozen lakes and rivers, an impressive sight!