August 24, 2015, by James

School log books as a source for investigating extreme weather events in the Western Isles during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

School Log Books

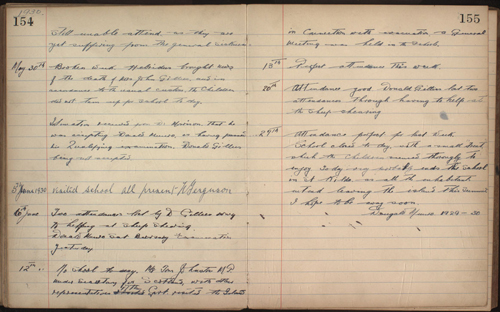

The main historical source material being consulted for the north-west Scotland case study are school log books, the keeping of which became compulsory after The Education (Scotland) Act of 1872 which sought to standardise education through the establishment of school boards in a region that was predominantly Gaelic speaking and where education had been provided by religious organisations like the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge (S.S.P.C.K.).[1] School log books have been used by historians of education interested in aspects of schooling for instance curriculum development, national standardisation and the professionalisation of teachers, they have a much broader relevance.[2] They frequently record extreme weather events as well as providing insight into the everyday lives of the remote island communities of the Western Isles and are extremely valuable given the relative scarcity of other source materials which have been utilised for the other case study regions.[3] Log books are a fascinating source which can be effectively mined for references to past extreme weather events. As well as recording school attendance (which was compulsory after 1872) and the educational and religious activities undertaken, the teacher often gave a daily summary of the weather in the log book remarking for example ‘weather good’, ‘weather warmer and fairer’, ‘weather very fine.’ However, these starkly contrast with the description of boisterous, cold, snowy conditions and snowstorms, stormy, wet and windy weather which was far more normal. Indeed an impression emerges from reading the log books that typically everyday winter weather was essentially extreme weather! There are also detailed descriptions of the impact of such weather, for example, when slates and tiles were blown off school roofs, windows broken, rooms flooded or when the school was snowed in.

Clearly weather hampered attendance, hence periods of stormy conditions, snow, high winds, heavy rainfall and droughts were frequently remarked upon. Roads and tracks could be blocked by snow or be impassable because of flood waters which meant that children could not make it to school. Strong winds and rain prevented children, especially infants leaving their homes. Also recorded were wider aspects of community life such as agricultural activities, for instance, spring work, the summer pasturing of livestock, harvest work, potato lifting, traditional pursuits like peat gathering and bird catching, and the loss of fishermen. They also record the outbreak of diseases like cholera, measles, scarlatina, small pox and typhus, and often contain incidental remarks about the state of living conditions for example the lack of adequate shoes and clothing for school children. Whilst the focus of the research project is the incidence of extreme weather, the information that log books contain reveals much more about the wider economic and social history of remote island communities which is deserving of further study.

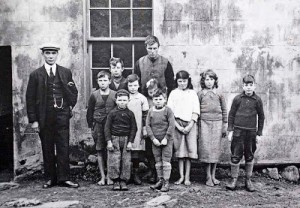

Case study: St Kilda School Log Book, 1901-30

To highlight the potential that school log books offer as a source, discussion will now explore the example of the St Kilda school log book which covers the period from 1901 until its evacuation in 1930.[4] It has been digitised through a partnership between the National Records of Scotland (NRS) and the Tasglann nan Eilean Siar (Hebridean Archives) and is freely available online.[5] Also available is the school log book for Mingulay, another abandoned island.[6] Examples of entries extracted from the school log book relating to weather are given below with the descriptions of the event and subsequent impact(s) in bold and underlined respectively as they will be entered into the Tempest (‘Tracking Extremes of Meteorological Phenomena Experienced in Space and Time’) database:

18 December 1901 ‘Today there is a heavy storm of wind and snow from the north. Thirteen of the children came out in the morning and as it was so stormy they weren’t called out in the evening.’

21 November 1904 ‘On account of a heavy fall of snow during last night, some of the infants are kept back with the severity of the weather. However they are doing entirely well.’

27 February 1905 ‘On account of the day being so wild, the majority of the scholars are kept back in the afternoon and I had to close the school.’

9 March 1905 ‘Today with the severity of the weather the greater number of the scholars are kept back. The attendances are a good deal broken up on account of the weather being so stormy.’

16 June 1905 ‘The weather throughout this week being so dry, and so favourable to the natives and their peat management. Owing to them being so busy, the school attendance suffered generally.’

5 December 1906 ‘Terrific gale. Four children turned out and the parents of those present came for them before one clock. School closed in afternoon.’

26 December 1906 ‘Deep snow and drifts, children unable to come to school for three days. As school was to have closed on Friday for usual new year holidays, we did not re-open until 8th January 1907.’

7 May 1907 ’Vey wet and rough weather which keeps the usual children away pretty often.’

14 April 1910 ‘Severe storm raging and as children did not turn up I did not open school at all.’

3 May 1911 ‘Owing to severe storm of wind and rain both school and church were flooded to the depth of several inches. Unfortunately the school had to be closed all day.‘

26 January 1912 Attendance for past month rather irregular, owing to stormy weather, and children being required at home in order to help with carding etc.’

15 November 1913 ‘Stormy day. I kept the children in till two o’clock, and closed for the latter part of the afternoon.’

27 August 1914 ‘Owing to the broken weather the catching of the birds is being prolonged. On wet days the children came to school so that four attendances have been made this week. The work is finished now however.’

7 January 1916 ‘Inclement weather. Attendance good. One girl sick.’

29 October 1917 ‘Owing to great storm only two scholars appeared this afternoon so no school was held.‘

28 February 1918 ‘Weather is intensely cold and stormy. Only three scholars appeared and school was not opened.’

8 November 1918 ‘Great storm raging. School not held as it is unsafe to enter the building for danger from falling stones or slates from church which has never been repaired since bombardment six months ago.’

23 January 1920 ‘Today being so stormy and wet for the children to come out, no school was held.’

6 February 1920 ‘Attendance low for the past fortnight owing to the stormy weather. Work progressing steadily.’

12 March 1920 ‘This week the attendance was interrupted by the severity of the weather and a bad cold among the children.’

10 December 1920 ‘Attendance good considering the weather.’

30 March 1921 ‘No school could be held these two days owing to a great storm and overflooding of both school room and church.’

24 February 1923 ‘Attendance good, considering the stormy nature of the weather.’

11 May 1923 ‘Owing to severity of weather and all the children having a bad cold no school was held today.’

9 October 1923 ‘Today being very stormy only six children came out.’

29 February 1924 ‘Attendance much affected by a severe cold among the children. Weather also very severe with a fall in snow.’

4 December 1924 ‘A severe gale was blowing this morning and the children could not come out. The weather improved about 1 o’clock so school was held in the afternoon. Attendance perfect for the rest of the week.’

16 January 1925 ‘Owing to the inclement nature of the weather the attendance was very low this week.’

13 February 1925 ‘Attendance good this week considering the stormy nature of the weather.’

24 January 1927 ‘Owing to severe storm and rain no one appeared in school this day.’

5 December 1927 ‘No school held today owing to a terrific gale raging from S.E. with blinding rain and snow drifts.‘

9 February 1928 ‘Owing to a raging gale today no school was held, as the children could not come out.’

22 November 1929 ‘Very good attendance this week considering the weather we have had.’

6 December 1929 ‘Perfect attendance this week in spite of bad weather.’

21 March 1930 ‘Perfect attendance this week also. Owing to a heavy fall of snow…’

28 March 1930 ‘Perfect attendance again this week single session of four hours on two days on account of storm.’

Whilst impressionistic the entries, which will be uploaded onto the project database, nevertheless provide insight into the different types of extreme weather experienced, the impact(s) which it had and the wider implications for the community. However is the example of St Kilda typical of school log books for the Western Isles more widely? What do earlier log books (1872-) reveal about extreme weather events pre-1900 and the period post-1930? To what extent did these remote island communities’ vulnerability to extreme weather events change over time, what was the nature of the impacts and what mitigation and resilience strategies did they employ? In order to gain a greater understanding of extreme weather events in the north-west Scotland case study area the research team are undertaking analysis of a wider geographical and chronological sample of school log books to allow for comparison.[7] School log books held at Castlebay Community Library, Isle of Barra, Lionacleit Community Library, Isle of Benbecula, Tarbet Community Library, Isle of Harris and Stornoway Library and Stornoway Historical Society, Isle of Lewis have been consulted.[8] Currently they are in the process of being analysed and inputted into a spread sheet so they can be corroborated with instrumental series for Stornoway (1857-present) and a series of indices devised which brings together qualitative and quantitative data. They could also be cross checked with local and regional newspapers, although this time consuming research is beyond the scope of this project.[9] It is also possible to identify many of the schools on historic maps such as the twenty-five inch to the mile first edition Ordnance Survey, as well as subsequent editions which correspond with the period of log book keeping. For example, the schools at Castlebay, Isle of Barra, the Monarch Isles also known as Heisker (uninhabited since 1942) and Tarbet are clearly marked.[10] There is greater map coverage from the 1890s particularly for the linear, planned settlements of the Isle of Lewis, for example, Bragar the log book for which begins in 1878.[11]

The impacts of extreme weather: historical and contemporary

Even before this analysis is completed, empirical based historical research highlights clear parallels with the present and potential for informing future mitigation and resilience strategies. Despite the passage of time, extreme weather continues to be a real threat to those who inhabit the Western Isles. In 2005 a family of five having recently moved to South Uist were tragically killed whilst attempting to escape from their flooded home when their car was swept into the sea from a low-lying causeway which linked Benbecula to South Uist. Flood risk management planning by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and the Scottish Government and projects like ‘The Sea as our Neighbour: Sustainable Adaption to Climate Change in Coastal Communities and Habitats on Europe’s Northern Periphery’ (Coast Adapt) have since explored coastline adaption and how efforts can be made to reduce the effects of extreme weather and improve resilience. The majority of contemporary impacts of extreme weather closely correspond with past events, especially those affecting the traditional industries of crofting and fishing which continue to be the backbone of the islands’ economies and are most vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather. The former relies on access to the machair which carpets the western coastline and is a rich habitat for flowers and wildlife, but is extremely vulnerable to coastal flooding and inundation. Similarly, storms, gales and hurricanes have disrupted fishing and frequently resulted in the loss of fishermen. Such disasters have had a significant impact on close-knit isolated island communities. Today fishing and aquaculture which is concentrated on salmon farming remain vulnerable by damage to slipways, fish farms and the influence of changing environmental conditions on fish stocks.

Further effects of extreme weather include disruption to the construction industry and utility supplies, a lack of drinking water which can be detrimental to health, a greater sense of isolation due to road closures and damage to harbours, jetties and strategic infrastructure such as airport runways or port link spans. There can also be difficulties in transporting people off the islands for healthcare due to the disruption of lifeline air and ferry services during periods of extreme weather. Extreme weather frequently results in damage to radio and telephone masts and power lines and the interruption of mobile phone coverage and internet connection. Houses and buildings are vulnerable to flooding and high winds and the weather can have a devastating impact on tourism businesses and events. Hopefully the school log books that have been examined by the project team and are in the process of being analysed will reveal the history of extreme weather in this case study region. By exploring past extreme weather events, the project places recent extremes like the Stornoway hurricane (8-9 January 2015) within an historical context, investigating not only the timing, frequency and impact(s), but also the processes by which certain events enter the cultural memory of a community, region and nation.

More information

Information can also be found on the National Trust for Scotland’s St Kilda website see: http://www.kilda.org.uk/.

Stornoway Historical Society see: http://www.stornowayhistoricalsociety.org.uk/.

For more recent extreme weather events see Dr Eddy Graham’s (University of the Highlands and Islands) Hebridean Weather Blog: https://uhi-mahara.co.uk/user/view.php?id=111.

References

- [1] For a recent history of education in Scotland see: R. Anderson, M. Freeman and L. Paterson (eds.), The Edinburgh History of Education in Scotland (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2015). It includes chapters by E.A. Cameron, ‘Education in Rural Scotland 1696 to 1872’ (chapter 9); J. McDermid, ‘Education and Society in the Era of the School Boards 1872-1918’ (chapter 11), C.R. Bischof, ‘Schoolteachers and Professionalism 1696-1906; (chapter 12) and F. O’Hanlon and L. Paterson, ‘Gaelic Education since 1872’ (chapter 17); For a survey of education in Scotland see: R.D. Anderson, Education and the Scottish People, 1750-1918 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1995).

- [2] For example see the work of Jane McDermid of the University of Southampton.

- [3] There is an earlier ‘Report on the State of Education in the Hebrides’ by Alexander Nicolson. Education Commission (Scotland) Parliamentary Paper (1867).

- [4] Hebridean Archives, Stornoway GB3002 IN4/50 St Kilda School, 1901-1930. I have previously explored the influence of weather on the island community of St Kilda in a previous blog: ‘St Kilda: Extreme Weather on the Edge of the World’, 4 August 2014. For an account of education on St Kilda see the ‘classic’: T. Steele, The Life and Death of St Kilda: The moving story of a vanished island community (Edinburgh, National Trust for Scotland, 1965), pp. 87-92.

- [5] See: http://www.cne-siar.gov.uk/archives/logbooks/stkildalog/index.html.

- [6] See: http://www.cne-siar.gov.uk/archives/logbooks/mingulaylog/index.html.

- [7] In a previous blog ‘‘The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides!’, 15 June 2015, Neil Macdonald provided a daily account of the research trip to photograph school log books for the Western Isles.

- [8] For the catalogue of Tasglann nan Eilean Siar (Hebridean Archives) which includes archives held across the Western Isles by historical societies, public authorities, businesses and organisations see: http://ica-atom.tasglann.org.uk/.

- [9] For the potential of newspapers see my previous blogs: ‘Sources in focus – Newspaper reports of extreme weather in the Western Isles in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’ (parts 1 and 2), 28 November 2014 and 10 February 2015 respectively.

- [10] See: http://maps.nls.uk/view/75104644, http://maps.nls.uk/view/75104767 and http://maps.nls.uk/view/75104653.

- [11] See: http://maps.nls.uk/view/82901472; Hebridean Archives, Stornoway GB3002 RC4/18 Bragar School, Lewis, 1878-2012.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply