June 30, 2014, by James

Getting into the archive – The Buildwas Earthquake of 1773: an earthquake or a landslip?

Cartographic and textual sources

Early in the morning of the 27th May 1773, a remarkable earthquake or rather landslip occurred at a place called ‘the Birches’ located on the hillside above the River Severn between Buildwas and Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, not far from the site of the present day Ironbridge power station (see featured image above). After days of rain and with the river in heavy flood, the hillside above slipped into the valley below. More than eighteen acres of land were carried forward, blocking the ancient river bed and stopping the current of the River Severn for several days. Great chasms thirty feet deep and between eight and ten yards long appeared in the hillside above, with pillars of earth four feet high left standing within the chasms, the ground below having moved a considerable distance.

When an earthquake occurred in the past it was a newsworthy event, attracting much interest with people recording what they or others claimed to have observed. In the British Isles the development of an educated and intellectually active body of the population who were literate and interested in religion, science and natural history, stimulated by the increasing availability of printed material, encouraged the recording of earthquakes and other natural events in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Before the development of modern disciplines, such as seismology many natural occurrences including earthquakes were interpreted as meteorological, the subject being essentially concerned with the empirical study of events rather than long-term processes. This tradition was characteristically qualitative and descriptive, and starkly contrasts with the modern practice of meteorology and science as quantitative pursuits.

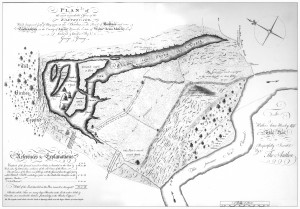

‘Plan of the Effects of the Earthquake which happened the 27th May, 1773, at the Birches in the Parish of Buildewas, and near Coalbrook Dale in the County of Salop. which was part of the estate of Walter Acton Moseley, esquire, produced by George Young, 1773.’

By far the most important source outlining the scale of the impact of the earthquake is the surviving plan produced by George Young and published according to an act of parliament, copies of which survive at numerous archives and libraries.[1] The plan details the change in the course of the River Severn, showing the alignment of ‘The Old Course of The Severn’ and ‘The Present New Channel.’ Marked is the ‘Former Situation of the Turnpike Road’, a house, garden and hedge which had been moved in the process, the remains of a barn which had been destroyed and ended up in the bottom of one of the chasms, and ‘Birches Brook.’ Marked on the plan were the many large breaches in the land on the north and east sides of the river, particularly in ‘The Birches Coppice.’

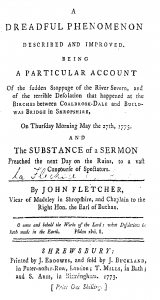

A number of written accounts which include several personal experiences survive, detailing the impact of the earthquake. The main descriptive account is that of Reverend John Fletcher (1729-85) the prominent minister of Madeley and contemporary of John and Charles Wesley.[2] Accompanying this account is the substance of a sermon which he preached the following day after the event on the ruins, to more than a thousand gathering spectators. There he made parallels between the phenomenon at Buildwas with Biblical stories (Job 1:13 and Genesis 5:32-10:1) emphasizing the wider religious context. An extract from Fletcher’s account describes how the supposed earthquake ensued and similarities with the effects of other extreme weather events:

‘the Birches saw a momentary representation of a partial chaos:- Then Nature seemed to have forgotten her laws:- The opening earth swallowed in a gliding barn:- Trees commenced itinerant: those that were at a distance from the river, advanced towards it, while the submerged oak broke out of its watery confinement, and by rising many feet recovered a place on dry land: – The solid road was swept away, as its dust had been in a stormy day: – Then probably the rocky bottom of the Severn emerged, pushing towards heaven astonished shoals of fishes and hogsheads of water innumerable: – The wood like an embattled body of vegetable combatants, stormed the bed of the overflowing river; and triumphantly waved its green colours over the recoiling flood: – Fields became moveable; nay, they fled when none pursued; and as they fled, they rent the green carpets that covered them in a thousand pieces. – In a word, dry land exhibited the dreadful appearance of a sea-storm; Solid earth, as if it had acquired the fluidity of water, tossed herself into massy waves, which rose or sunk at the back of him who raised the tempest. – And, what is most astonishing, the stupendous hollows of one of those waves, ran for near a quarter of a mile thro’ rocks and stony soil, with as much ease as if dry earth, stones, and rocks, had been a part of the liquid element.’[3]

Fletcher’s account includes several personal recollections. Samuel Cookson, a farmer who lived half a mile below the Birches on the side of the river where the landslip occurred, recalled that he had been frightened by ‘a sudden gust of wind, as he thought, which beat against the windows as if a great quantity of hail show had been thrown with violence at them.’[4] People living in a house above Buildwas Bridge which was more than a mile away from ‘the Birches’, but on the same side of the river, recalled that their house shook violently so they left the house taking goods and possessions with them.[5] That night the house and adjoining buildings were shaken again and demolished.

There were numerous other contemporary accounts describing the phenomenon, such as that of T. Addenbrooke’s dated 4 June 1773 which appeared in the Annual Register for that year and drew upon Fletcher’s published account.[6] In addition to newspapers, the event was remarked on in personal diaries and letters. Descriptions were written by Mark Gilpin, a Quaker and clerk to the Coalbrookdale Company and Abiah Darby (1716-1794), wife of the second Abraham Darby (1711-1763) who described the scene in a letter to her children.[7]

An earthquake or a landslip?

Whilst the surviving plan gives the cause to be an earthquake, there was much debate at the time as to the precise cause of the event. The late eighteenth century marked a point of transition in the way that natural events were reported. Evident in the reporting of the Buildwas earthquake is the shifting emphasis placed on the physical causes, rather than theological or social explanations for the event. Those who argued it was a landslip cited the recent heavy rainfall and the closeness of the River Severn which at the time was in flood and could have eroded and undermined the bank, undercutting the hillside. One of the main causes of the earthquake or landslip appears to have been heavy rainfall which meant that the river was in flood and, in this respect it is possible to supplement qualitative evidence with quantitative data. Indeed monthly precipitation figures for England and Wales supports this view, showing that the month of May 1773 had exceptionally high levels of precipitation with 151.8 millimetres being recorded.[8] It is also possible that changes in land management, such as, the removal of trees may have increased the areas vulnerability to a potential landslip.

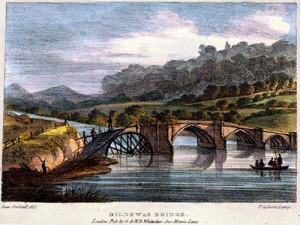

Painting of Buildwas Bridge before the earthquake in 1773 from Thomas Harral, Picturesque Views of the Severn (London, 1824).

In contrast those who interpreted the phenomenon as an earthquake suggested that the same rock composed the river bed and the higher ground, and that the area had always been free of landslips.[9] It was also claimed that an earthquake had been felt nine miles away to the north-east at Hennington in Shifnal Parish on the 22nd June 1773 ‘tho’ the earth did not open there, as it did at the Birches.’[10] There are, however, no records corroborating that an earthquake occurred in England and Wales on that day which could substantiate the claim that it an earthquake. It is significant that rather than putting the event down to an act of God, there was a clear recognition of the physical processes of nature which acted independently, an explanation being sought through comparison with previous examples from England and Wales, and Europe more widely. The occurrence of an earthquake as a physical cause that triggered the landslip cannot be ruled out. However, it seems probable that the so-called Buildwas earthquake was not an earthquake at all, but rather a landslip caused by a series of factors that made the slope vulnerable to failure.

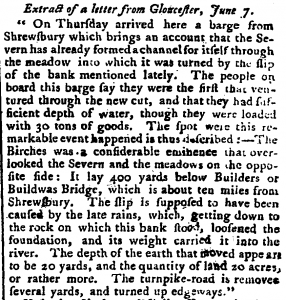

News of the Buildwas earthquake

News of the earthquake was circulated widely, it being reported in national newspapers including the London Evening Post, the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, the London Chronicle or Universal Evening Post, the General Evening Post and the General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, as well as local and regional newspapers. The earthquake disrupted the navigation of the river which at that time was an important inland transport route, traffic on the river peaking in the mid-eighteenth century with boats called Severn ‘trows’ carrying coal, timber, pig iron, malt, building stone and lime, raw cotton, salt, manufactured iron goods, paper, earthenware and cheese.[11] An extract of a letter sent from Gloucester published in the London Evening News on the 8th June 1773, records the disruption to navigation which the earthquake or landslip caused, although this was resolved as the river formed a new channel (‘new cut’) with sufficient depth for a vessel laden with 30 tonnes of cargo to navigate. It also gave the cause of the earthquake or landslip as being the result of the ‘late rains’ which, ‘getting down to the rock on which this bank stood, loosened the foundation, and its weight carried it into the river.’[12] There are also reports of many vessels having fallen on their sides in the drained river bed downstream, being lost when the river finally found a new course past the blockage.

The considerable impact of the earthquake meant that it was remembered by local people, becoming an important event in the history of the locality. Hence, Captain H.R. Moseley of Buildwas Park wrote in his notes on the parish history of Buildwas:

‘Landslip on 27th May 1773 some 23 acres of land (including parts of the Birches Coppice & a cottage on the steep northern bank of the river, close to the boundary between the parishes of Buildwas & Madeley, slipped badily down the hill side, destroying the main road & altering the course of the Severn. This place is still known as “The Slip.”’[13]

‘Birches Coppice’ and the site of ‘The Slip’ is still marked on the modern Ordnance Survey map (655,047) and today, the Ironbridge Gorge continues to experience landslips requiring remedial work to maintain the stability of the roads and buildings in the area.[14]

References

- [1] The British Library, London Maps K.Top.36.24.2.b.; The British Museum, London 1856,0712.52; Herefordshire Record Office, Hereford 96/105; Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury (hereafter SA) 690/13.

- [2] J. Fletcher, Account of the phenomenon at the Birches: A dreadful phenomenon described and improved being a particular account of the sudden stoppage of the River Severn, and of the terrible desolation that happened at the Birches between Coalbrookdale and Buildwas Bridge in Shropshire, on Thursday morning May the 27th 1773, and the substance of a sermon preached the next day on the ruins, to a vast concourse of spectators (London, 1773) BL 4474.c.81.and 291.b.30, SA M 15. For biographical information: John Fletcher, 1729-1785, Vicar of Madeley (Manchester, John Rylands University Library, 1985); Patrick Ph. Streiff, ‘Fletcher, John William (bap. 1729, d. 1785)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9733, accessed 24 March 2014].

- [3] Fletcher, Account, 8-9.

- [4] Fletcher, Account, 9-10.

- [5] Fletcher, Account, 7.

- [6] T. Addenbrooke, ‘An Authentic Account of the Earthquake at the Birches, about half a Mile below Buildwas Bridge, and about a Mile above the Bottom of Coalbrookdale, Shropshire’, The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1773 (London, J. Dodsley, 1774), 207-9.

- [7] SA 1987/64/1; N. Cox, ‘Darby, Abiah (1716–1794)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/55521, accessed 25 March 2014]; B. Trinder, ‘Darby, Abraham (1711–1763)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7138, accessed 25 March 2014].

- [8] By comparison the monthly totals for the other months of the year were 68.8 (January), 72.4 (February), 19.9 (March), 54.4 (April), 65.5 (June), 37.3 (July), 83.6 (August), 141.6 (September), 112.3 (October), 125.0 (November) and 101.2 (December) millimetres, with an annual total of 1033.8 millimetres, a monthly average of 86.15 millimetres. L.V. Alexander and P.D. Jones, ‘Updated precipitation series for the U.K. and discussion of recent extremes’, Atmospheric Science Letters, 1(2001) doi:10.1006/asle.2001.0025.

- [9] Fletcher, Account, 21.

- [10] Fletcher, Account, 26.

- [11] For more information concerning the traffic of the River Severn: M.D.G. Wanklyn, ‘The Severn Navigation in the Seventeenth Century: Long-Distance Trade of Shrewsbury Boats’, Midland History, 13, 1 (1988), 34-58; M.D.G. Wanklyn, ‘The Impact of Water Transport Facilities on the Economies of English River Ports, c.1660-c.1760’, Economic History Review, New Series, 49, 1 (1996), 1-19.

- [12] London Evening News, 8 June 1773.

- [13] SA 6001/4353.

- [14] Ordnance Survey (2005). Sheet 242, Telford, Ironbridge and The Wrekin. 1:25,000.

Thanks so much for this interesting post! This even really seems to have entered into local lore – I came to it through a travel account penned in 1806, in which the traveller records “Between Collbrook Dale and Bildwas there was on 27 May 1773 a great rend and slip of the rock and side of hill towards the river, at a place called the Beeches on the Estate of Walter Seton Mosely.” Thanks for helping me to understand what he was talking about!

*event*

Thanks for the comment, Angela. It’s always good to find out there is additional evidence out there to help build a story. I’m sure ‘team extreme’ member, James – who wrote this particular blog- will be pleased to hear this. Many thanks, Georgina.

I am pleased that you have found the blog useful. This fascinating event came to my attention when the project first started, due largely to the survival of the rare plan. This blog is a condensed version of a paper which I have written analysing the surviving plan, numerous contemporary accounts and newspaper reports. Reconstructing the course of events related to the phenomenon and its aftermath provides a really interesting individual case study of the causes of the supposed earthquake, its impact in a locality and contemporary debates about the relationship between religion and science. It also sheds light on aspects of the economic, social and religious history of the Ironbirdge Gorge which, at that time, was according to Charles Hulbert in 1837 ‘the most extraordinary district in the world.’ Feel free to email if you would like further information – I would be grateful for the reference to the travel account. James

I attended a presentation on the site of the The Lloyds Stabilisation Project when the details of a letter sent to one of the Darby’s from a local resident was shown which described how he saw early one morning a complete rock form come away and tipped over to the other side of the Gorge. This was explained as evidence that the Gorge is still moving.

Was this the same event or another occasion?

Thanks John for your recent comment on the Buildwas earthquake blog. I know that the Ironbridge Gorge has a long history of slope instability as I am sure you are aware. Without reading the letter I obviously couldn’t say whether it referred specifically to the event that occurred on the 27th May 1773 or another similar event. In Fletcher’s account reference is made to an earlier event although not of a comparable scale and there have been numerous landslips since. Hence the Ironbridge Gorge is a case studies of the British Geological Survey see: http://www.bgs.ac.uk/landslides/IronbridgeGorge.html

Several letters do survive recalling the Buildwas earthquake. These were addressed to or written by members of the Darby family.

For example one such letter dated 28 May 1773, the day after the event, was written by Mark Gilpin, a Quaker and clerk of the Coalbrookdale Iron Company. He wrote that at about four o’clock the previous morning, more than thirty acres of land adjoining to Birches Brook on the Buildwas side of the River Severn ‘moved from its situation. The small coppice near the river, in which grew about twenty large oaks, was removed into the channel, so that part of it rested on the opposite shore and entirely stopp’d the course of the River, which was then very high’, presumably because of the ‘late rains’. ‘… a few of the trees fell’, whilst others remained as if they had always grown there. The land above the coppice, which totalled about thirty acres followed with ‘hedges and trees remaining, except a few that are overturned’. He noted that the turnpike road had been ‘removed about thirty yards and indeed to all appearance forever impassable. Hollows are changed into mounts and mounts into hollows’. He recalled that a barn had been moved about thirty yards into a great chasm where ‘it remains a heap of rubbish’, and although the house that stood near the barn had received little damage, a hedge that joined to the garden belonging to the house had been moved more than fifty yards. Gilpin described the land as ‘full of cracks from six inches to above a yard wide and very deep, some small pyramids of Earth standing in the middle’, the land being formed through Wilkinson’s meadow opposite where the coppice formerly stood. He remarked that he hoped the stream would ‘in a few days’ work itself navigable’, although he recognised that there was ‘no probability of it ever remaining in its old course’.

A further letter written by Abiah Darby (1716-94), wife of the second Abraham Darby (1711-63) to her children described the scene writing:

‘what a terrible slip has been, the river now runs in the opposite meadow three barges are comed down & rest above the bridge – but no passage for anything round the slip. Some think it will be years before if ever there be any channel – Mark [Gilpin] said so last night – but today hopes there may in time – thousands of people did go & are continually going to see it – John of Fletcher preached to them at the place last evening, & has given notice he will preach there this at 6 o’clock. It is deemed to be an earthquake – to be sure it was one – and the means providence used might be the water undermining and blew it up – what providence for the poor man Roberts – he had just time to get his family out, & happened to run the right way, for if they had run any other than yt they did they wou’d have been swallowed up’.

I hope these examples are of interest. Please do not hesitate to contact me to discuss this notable event further.