May 18, 2014, by Mark Gallagher

Soderbergh Goes Legit

By Mark Gallagher, Associate Professor, Dept. of Culture, Film and Media, University of Nottingham

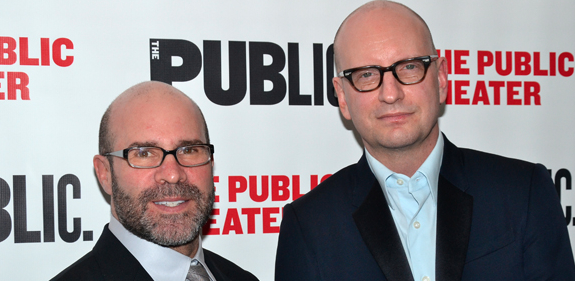

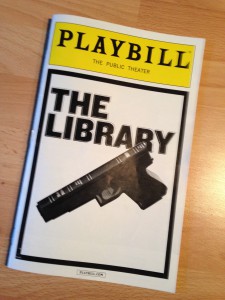

New York City recently hosted the 12th edition of its homegrown Tribeca Film Festival. Surely this would be a good time to visit the city and catch the newest offering from Steven Soderbergh (whose work and career I explore in my recent monograph, Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood). As it happens, that offering wasn’t playing at the festival, or on any local screen. Instead, it was in the notably unmediated art form of live theatre—the short-run play The Library, at the off-Broadway Public Theater, in Greenwich Village.

Some of Soderbergh’s films (such as the 2005 micro-indie Bubble) have found only small, niche audiences. But with just over three weeks of previews followed by a 13-day engagement, The Library—alongside Soderbergh’s previous live-drama effort, Tot Mom, staged in Sydney in 2009—will likely stand as one of the filmmaker’s most rarefied works as measured by audience size. It enjoyed a capacity crowd when I saw it a few days after its opening, but even if each of the 17 post-preview shows drew a full house (in its 299-seat venue), just over 5,000 people would have been able to see it.

Beyond reminding us why short-run theatre is not a mass art form, these numbers signal the different canvases on which Soderbergh—and first-time playwright Scott Z. Burns, screenwriter of the Soderbergh-directed The Informant! (2009), Contagion (2011) and Side Effects (2013)—has recently chosen to work.

As I recap in my current work on his post-cinema, arguably post-independent activity, this is the Soderbergh—avowedly retired from feature filmmaking after delivering Side Effects and the telefilm Behind the Candelabra last spring—who has of late distributed a Bolivian brandy, composed a novella, Glue, on Twitter, and crafted a website dense with film commentary, purchasable ephemera including aggressively obscuritanist T-shirts celebrating past films, and re-edits such as a Psycho mashup and a Heaven’s Gate evisceration. This is also the Soderbergh now fine-tuning a limited-edition headphone launch, and of course, an as-yet underpromoted television series, The Knick, for HBO sister channel Cinemax to begin airing this summer.

The Library combines the tone of TV procedurals Law & Order or CSI with the thematics of an ABC Afterschool Special, in the best possible senses of both. Soderbergh and Burns use these genre templates—procedural and teen-centered family melodrama, respectively—to mount political and social critiques. Their three films together used black comedy, disaster film and pill-popper thriller to illuminate the workings of agribusiness, Big Pharma, and other engines of global capitalism. In The Library, the targets are organized religion, bourgeois civic-institution hypocrisy, and in the background, a publishing industry cynically flogging uplifting narratives of victimhood.

The Library did not receive stellar notices. Major critics offered consensual praise for Chloë Grace Moretz’s lead performance and some staging elements, but were generally disappointed with characterization and storytelling overall. Reviewers particularly faulted its schematic plotting, though the critical focus on a predictable storyline and limited psychological insights may mask the drama’s notable ability to engage with multiple, highly topical subjects in a contained, minimalist production.

Ultimately, the drama’s uneven critical reception carries far less significance than the risk-taking nature of the enterprise, with successful screen artists testing storytelling techniques in a medium in which they have little or no experience. Soderbergh does not claim the long relationship with theatrical drama enjoyed by such luminaries as Ingmar Bergman or Mike Nichols (both of whom, like Soderbergh, have also worked in television; Soderbergh has also recorded multiple DVD commentaries with Nichols, for the Nichols-directed films Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? [1966], The Graduate [1967] and Catch-22 [1970]). For Hollywood or indie-sector professionals such as Soderbergh and Burns, the move to stage drama does little to ensure career sustainability or progression. Instead, this creative choice represents both men’s efforts to expand their artistic palette, offering possible rewards in terms of legitimation though also considerable risks—in this case the judgments of drama critics and audiences who have not necessarily followed or supported the pair’s screen activity.

Film directors taking on live drama relinquish much of their tradecraft: locations, editing, lens choices and filters, camera position and more. Soderbergh, interviewed with Burns on Charlie Rose about The Library, refers to the challenge of finding a stage parallel for the close-up. Perhaps most notably, the stage director is not necessarily on set for each performance, so while he and playwright craft the drama, they do not execute it. For Soderbergh, this is not so great a departure from past practice as one might surmise. In his screen work, not least his Section Eight production shingle with actor George Clooney, Soderbergh has formed many collaborative relationships with actors. And in the spirit of his acknowledged 1960s and 1970s forebears such as Nichols and Alan J. Pakula, his directing has long privileged actors and performances, evident among other places in his management of ensemble casts for Traffic (2000), the Ocean’s series (2001-2007) and Contagion, and in work with serial collaborators such as Clooney and Matt Damon.

Likewise, Soderbergh and Burns’ gate-crashing of the drama world did enjoy the financial backing and personal support of many Hollywood and US-television figures. The Library’s backers included Los Angeles’ Kennedy/Marshall Company, the film shingle of producers Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall. Meanwhile, its premiere drew performers such as Michael Douglas, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Jon Hamm, Oscar Isaac, Heather Graham and David Duchovny.

Film and TV industry DNA literally took center stage as well. Arguably the play’s greatest on-stage asset was its lead, Chloë Grace Moretz, star of the recent Carrie (2013) remake and co-star of the Kick-Ass films (2010, 2013) and Hugo (2011). She was surrounded by a showcase of actors with long and storied careers, including indie-film stalwart Lili Taylor (star of Dogfight [1991], I Shot Andy Warhol [1996] and other touchstone works, recently returned to high visibility with last year’s The Conjuring), onetime Spy Kid (2001-2011) Daryl Sabara; journeyman actor Michael O’Keefe, best known as the protagonist of 1980’s Caddyshack, though subsequently with a lengthy television and film résumé; indie-film actress, writer and director Jennifer Westfeldt, whose CV includes Kissing Jessica Stein (2001) and Friends With Kids (2011); and Law & Order, NYPD Blue and 24 alumnae Tamara Tunie. (Stage, TV and film veterans Ben Livingston and David L. Townsend rounded out the small cast.) Many of these performers shuttle among stage and screen work. Nonetheless, their gathering for this production reminds us that contemporary creative-industry cross-pollination happens not only in buzz-worthy web series and in so-called quality television and but also (and still!) in resolutely offline spaces.

Beyond assembling this idiosyncratic cast, Soderbergh oversees a range of formal achievements arguably outside the provisions of the feature filmmaking on which his reputation largely rests. Set in a handful of small-town interiors, The Library does not have to mimic the globe-trotting of productions such as Traffic (2000), Che (2008) and Contagion. It dispenses also with the period realism apparent in the production design for the forthcoming The Knick (and seen too in previous Soderbergh work such as King of the Hill [1993] and The Good German [2006]). And rather than sacrificing only some filmmaking resources, Soderbergh jettisons nearly all of them, in particular production design. Riccardo Hernandez’s sparsely appointed set—consisting only of a handful of chairs, tables resembling hospital gurneys and a modernist illuminated ceiling—grants primacy, and often physical and emotional vulnerability, to the performers.

Stylized sound and lighting textured the production as well, further distancing it from the language of mainstream, realist screen narrative. Semi-experimental recorded sound coupled with the irregular soundscape of the thundering #1 train running beneath the Public Theater’s Lafayette Ave location. The production was especially notable for its expressive lighting, homologous to recently celebrated work of light artist James Turrell, such as his 2013 Guggenheim rotunda installation. A bit remarkably, Soderbergh claims not to have been familiar with Turrell’s work (though presumably lighting designer David Lander was conscious of it in his execution of Soderbergh’s ideas). In the play, lighting works as both supplement and counterpoint to narrative, cueing emotions but also crafting a surround for viewers’ more abstract, non-rational engagement.

Arts and screen scholars are busy people, not often gifted with the free time or resources to take in the films, television programs and mountains of other artworks that capture our interests and energize our research. But my impromptu cultural vacation—that is, fieldwork-research trip—reminds me of the value and pleasure of limited-run narrative and performance. (To defray any impression of wholesale unawareness that the theatrical medium exists and thrives, I should add a caveat: I am not a total philistine. I’ve seen thousands of stage performances. This century, though, these have mostly involved long-haired men wielding guitars, or short-haired men perched over laptops.)

Yes, we live and work amid an evolving regime of global screen-artifact traffic, online circulation, and digital delivery and scholarship. Still, analog artworks and experiences can continue to demonstrate entertainment-industry workers’ boundary-pushing. These works continue to inform our understandings of the expanses, as well as the niches, of contemporary cultural production.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply