June 1, 2017, by Rights Lab

Slavery from Space

By Bethany Jackson and Dr. Jessica Wardlaw

Modern slavery remains a pressing human rights issue, with the latest Global Slavery Index (2016) estimating that 45.8 million people are currently enslaved globally. India alone accounts for over 18 million affected individuals, in industries ranging from domestic work and construction to agriculture and quarrying. Efforts to eradicate this pervasive human rights violation have ramped up in the last couple of decades, but the widespread nature of modern slavery means that our understanding of its practice continues to evolve. New methods for tackling slavery in certain industries are essential to free these enslaved people and build resilience in vulnerable populations.

NGOs have traditionally relied upon ground-based methods to locate sites of bonded labour, but remote locations, conflict zones and politically unstable areas can be highly dangerous for personnel to access thus restricting the reach of their efforts. Geospatial techniques have now emerged to provide NGOs with another avenue for data collection, as they provide the opportunity to track human rights abuses remotely and identify many more previously unknown locations of slave exploitation. The use of satellite imagery, captured almost continuously in both space and time, is an important innovation for the human rights sector, who can use images to focus interventions more effectively and efficiently with regards to limited time, manpower and financial resources. This will contribute to long-term efforts to eradicate slavery.

Satellite imagery has never been more cheaply or freely available and NGOs have already used it to detect likely locations of human rights abuses, but its potential for identifying likely locations of slave exploitation remains untapped beyond a few examples like the identification of child labour camps in Bangladesh last year or Walk Free Foundation’s research into slavery on Lake Volta in Ghana.

. Whilst satellites successfully automate data collection, computers remain inferior to even the most untrained human eye for analysing images to identify patterns. Currently, the growth in volume of satellite images easily outpaces the amount of human resource available to process it so NGOs have followed scientists in other fields and turned to crowdsourcing. Projects such as Amnesty Decoders seek to engage hundreds and thousands of volunteers, whose analyses are combined and compared to dilute any individual human error, to reach a consensus.

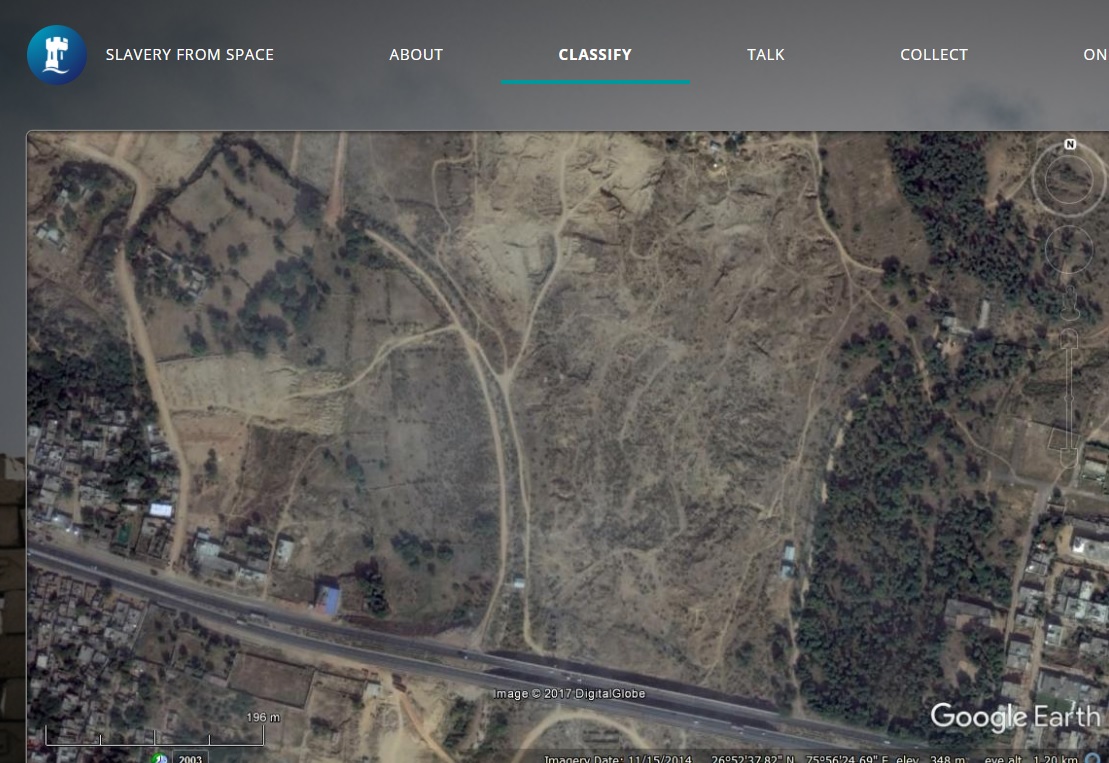

We are proud to share with you our project “Slavery From Space,” which seeks volunteers to help researchers trawl through tons of satellite images to look for and mark brick kilns. These kilns support the construction industry as it struggles to meet the demands of a population explosion, but have huge potential to be monitored in near-real time because they are visible in satellite imagery. The primary objective of Slavery From Space is to paint a more precise picture of the prevalence of slavery in areas where we both know and don’t know it is happening. Volunteers will tag locations for investigation on the ground, and also help policy makers reach more educated, evidence-based decisions. As well as improving our understanding of modern slavery, crowdsourcing can also engage the online community and raise awareness of modern slavery much more widely.

Excitingly, this is just the beginning. Slavery From Space will grow as we add more imagery and seek other signs of slavery in future. You can also participate in a distance-learning MA in Slavery and Liberation that begins this September, and a free online course, Ending Slavery: Strategies for Contemporary Global Abolition, which includes a unit on the use of geospatial science for ending slavery.

Bethany Jackson is a PhD Student in the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham, funded by the University of Nottingham’s Research Priority Area in Rights and Justice. She is studying the scale and impact of the brick kiln industry in Asia, using a range of satellite imagery.

Dr. Jessica Wardlaw is a postdoctoral research fellow with University of Nottingham’s Research Priority Area in Rights and Justice and the Nottingham Geospatial Institute, working on the use of geospatial science to tackle modern slavery.

I learned a lot from the insight you shared. Thank you!