August 22, 2016, by Michael Jennings

When digestive disease meets art – exploring your inner self

Written by Dr Giles Major, Clinical Assistant Professor in Gastroenterology, Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre.

How are your bowels? It’s a simple enough question but in clinical research life is never that straightforward. In the Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre we need to quantify ‘bowel function’ so that we can measure differences between health and disease. This matters: if we don’t have a measure that reliably reflects outcomes for patients, then we can’t do meaningful clinical trials of new treatments. We also want to understand the mechanisms that underlie digestive disorders.

We use a variety of techniques to study the bowel, either to observe the mucosa that lines its surface or to measure muscle contraction. Both of these involve insertion of some sort of sensor into the gut, either through the mouth or ‘from below’. Not only is this uncomfortable for the volunteer, but also the presence of the sensor may alter how the gut works.

An alternative approach is to use cross-sectional imaging. We use Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to image the bowel, working with the Sir Peter Mansfield Imaging Centre in a collaboration over 20 years that has made the GI MRI Research Group a world leader.

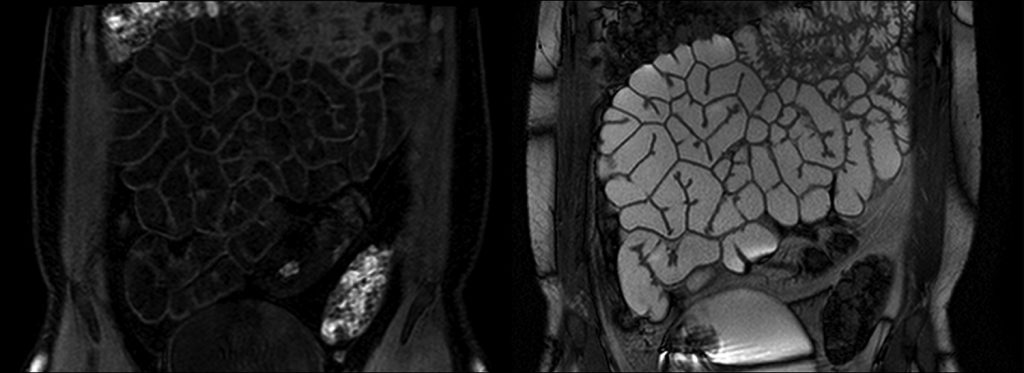

MRI uses the intrinsic magnetic properties of certain chemicals to detect their abundance in the body. It is particularly sensitive to levels of water and fat, two substances found in large amounts in the human body. In MRI the body is divided into small cubes (voxels) and an intensity level is assigned to each. This creates an ‘object map’ of whatever is scanned. Top: a 3-dimensional object map of the colon with different segments colour-coded. The MRI scanner can be programmed to measure water and gas within the colon. Bottom: a scan showing the small bowel, highlighting different substances. Water in the bowel is either dark (left) or light (right). For comparison the bladder is included at the bottom of the scan.

One challenge for the group is to keep questioning what we think we know about the gut, and what we need to know. This involves constant re-examination of how we conceptualise the role of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. For the last two years we’ve been lucky to work with Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva, the artist behind the exhibition ‘Making Beauty’ currently showing at Lakeside’s Djanogly Gallery.

Elpida has spent time with us, and colleagues in Norwich and London, to see how we work and apply our investigative methods in both research and clinical practice. She has also spent time with some of our patients, participants in research studies, including intimate interviews about their health and its impact on daily life.

I have deliberately not asked for a sneak preview of the work that Elpi has created as I want to experience the show when it’s ready. I’m hoping that it will surprise me by presenting a fresh perspective on what I look at every day. It may also teach me something about my patients. As scientists we may ‘see’ the GI tract but patients bring their own perceptions of how their gut works. I can see that patients with chronic problems develop a relationship with their condition. This isn’t always easy to discuss in clinic.

For me, the role of Art in Science is to communicate the unmeasurable: to explain the bits in between our scales and parameters that take physiological research into the clinical domain. ‘Quality of life’ is an overworked phrase but different artistic media allow us to consider what contributes to the quality of our lives in a way that a written article, or a blog post for that matter, cannot. How are your bowels? Tell me once you’ve seen the show.

Making Beauty runs from 20 August to 30 October at the Djanogly Gallery, Nottingham Lakeside Arts and is accompanied by a series of talks, tours, lectures and workshops. Admission is free and you can find out more on the Nottingham Lakeside Arts website.

As an artist with a scientific academic background I not only find this idea interesting but also welcome the crossover.