December 17, 2015, by Editor

Monetising music

The Melbourne suburb of Brunswick, located 6 km north of the city centre, has a history of radical politics, ethnic and cultural diversity and also hosts the annual Brunswick Music Festival. In that sense it is appropriate setting in which to find Wick Studios, a space dedicated to the musical economy in its various forms. A vast sprawling complex, consisting of as many as 15 rehearsal rooms, two recording studios and a photography/film studio for capturing visual images, it bears the signs of a recent multi-million investment by its owners. In the context of the disruption that has swept the music industry in recent years, such investment is unusual, especially given the fate of so many similar facilities elsewhere in the world.

Challenges and opportunities in the new musical economy

My tour of the studios in October 2015 was a result of an invitation from the studio’s Director of Entertainment and Development, Lynn Robnett, who had attended a talk I gave at the University of Melbourne a few days earlier, which in turn was based on my recent book, Reformatted (University Press, 2014).[1] Robnett, who had been headhunted from her previous career in the Los Angeles music industry to lead the day-to-day operations of the studios, challenged me on what she considered an overly pessimistic reading of the state of the musical economy. I had chosen to focus on the problems facing artists and institutions due to the destabilisation of the music industry, caused first by the rise of MP3 and peer-to-peer networks, and then by the further difficulties of reduced income for artists as a result of a re-stabilisation around streaming platforms such as Spotify. However, Robnett drew attention to the opportunities presented by the Internet, various social media platforms and the production of readily available data that up and coming artists might use to their advantage. These and other developments enabled artists to enter the industry more easily. The cost of recording had fallen dramatically, for example, while services such as YouTube, Facebook, Shazam and Twitter facilitated self-generated marketing campaigns, providing geographical insights into fan bases, enabling more efficient, targeted touring schedules. While the new musical economy certainly threw up challenges, and a requirement for artists and bands to be more self-sufficient and self-directed, with a capacity to withstand economic precarity (see a particularly insightful paper by Brian Hrac’s and Deborah Leslie which explores this issue in a case study of musicians based in Toronto, Canada), those that were able to adapt could develop a career without the hurdles and obstacles put in their way by traditional gatekeepers such as record labels and recording studios.

After my visit I was certainly impressed by the energy and commitment that Wick directed to developing a business model that fitted the new parameters of the music industry. Recognising the declining value of a pure recording studio model, each of their rehearsal rooms were fitted with audio technology that enabled artists to connect to any console in the facility via a laptop and turn the rehearsal space into a recording studio if required They were ideally located to pick up on the emergence of new musical trends and talent not only in Melbourne, a traditional centre of the music industry in Australia, but also in the rest of the country, as regional acts routinely included the city on their tour schedules. The studio also actively cultivated networks and contacts through the acts that used the studios, either to prepare for gigs in the city or simply to try out new material, and actively encouraged new artists to use the complex. They had a performance space, with a bar, for ticketed live events, which provided a valuable income stream, in line with the rest if the music industry. Wick also looked for opportunities to move up the music value chain, signing contracts with artists where appropriate, such as publishing or management deals, operating in the space vacated by record labels as a ‘management company with assets’. They were relaxed too about who would use the space, seeing the studios as a community resource, and rooms could be hired out for a range of uses including, yoga classes and meetings.

This visit was a useful corrective to my default pessimism, although the musical economy clearly remains a challenging environment for musicians and institutions alike, as I reflected in an interview with the University of Melbourne’s Up Close research-focused podcast series, which has recently been made available online. The challenges facing artists were closely appreciated by both the interviewer, Peter Clarke, whose son was making a career in the industry as a hip hop artist, and the studio engineer, Gavin Neubar, who was a member of a local band, Nightflite. Both were able to reflect on personal experiences that informed the questions I was asked that ensured it was an enjoyable and – for me at least – thoughtful interview.

Generating income in the music industry

One of the key issues that I seek to explore in my research, and which I explored in the interview, is how industries reproduce themselves after a major disjuncture, such as a crisis, where taken for granted mores and a desire for ‘business as usual’ is thrown into question. New kinds of business models and performances are urgently considered and experimented with in a search for income and value. Currently within the music industry, there are at least three ways of generating income to reward artists and companies for the time and investments they make.

The first is through intellectual property rights, extracting a rent from the copyright imposed on sound recordings. This was the traditional engine of the musical economy in the 20th century but was undermined by the availability of free music in MP3 format from 2000 onwards which in effect opened up the closed digital format of the compact disc. As Allan Watson argues in both written and video reports for Nemode, new digital business models are now stabilising, but the industry is struggling with a three-pronged process of transition, which includes a shift from analogue to digital, from downloads to streaming, and from PCs to mobile devices. It is also dealing with a more traditional problem related to equity, given that rights holders, such as record companies, and the platforms that facilitate streaming, currently retain the majority share of income, which makes earning a sustainable income from such distribution methods difficult for all but the most successful artists. There have been various protests about this from artists, with some established acts, such as Thom Yorke and Taylor Swift, going as far as to remove their repertoire from Spotify in protest at the paltry royalty rates, which Watson argues have been estimated to be as low as $0.0011 per stream.

Second, and due to the absolute decline in income derived from intellectual property rights, income from live performance has accounted for the largest source of revenue in the music industry since at least 2008. In this sense the traditional business model of the music industry has been inverted: in the past tours were undertaken to promote the sales of recorded music. However, as recorded music revenues have fallen, and performance-based income has increased, recorded music now serves as the marketing device to drive ticket sales. But, as performance has become more important, so the market has filled up. There is more competition between artists for the slots that do exist. Indeed, as RMIT PhD student Sarah Taylor has revealed in her archival research on my host city of Melbourne, while the total number of performances increased, the average number of gigs performed per artist declined steadily over the past 30 years. This was caused largely by growing competition for performance opportunities, but more recently it has been exacerbated by the closure of venues, victims of noise control regulations imposed by local governments in gentrifying neighbourhoods, a process not unique to Australia but experienced in cities across the global musical economy. Therefore, live performance may produce more earnings than royalties for most musicians over time; it is just that those earnings are, on average, quite low.

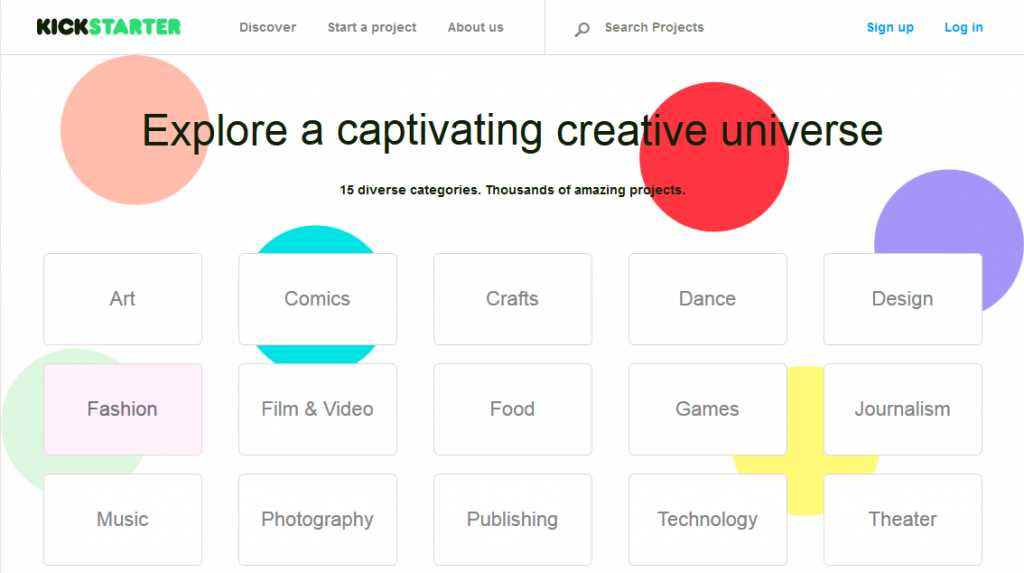

A third source of revenue is to convert fan-enthusiasm into income that goes beyond the traditional means of selling sound recordings or concert tickets. One option is to enter into a brand partnership with another company, one that wishes to trade on the image and audiences that artists have already constructed, effectively buying their endorsement. While many of these deals are successful, and can give artists a useful injection of cash, they can on occasion go spectacularly wrong as brands collide. For example, consider the deal between Apple and U2 where the latter agreed that the release of their 2014 album, Songs of Innocence, could, in return for a fee, be distributed as a free product through iTunes to help promote the launch of the iPhone 6. However, while initially lauded by media commentators, such was the negative reaction by iPhone users to the unexpected and unasked for appearance of U2 songs in their iPlayer catalogues that less than a week after the launch Apple were forced to release a U2 removal tool, followed by an apology from the band, admitting that “we got carried away with ourselves”. Quite simply, for every U2 fan that welcomed the free music, there were many more ‘anti-fans’ that took exception to what they saw as the corruption of their digital music catalogues. An alternative way to capitalise on fan enthusiasm is to turn to crowdfunding platforms, where artists can raise money for ‘projects’ by offering not a return on investment but some kind of reward, which might be material or experiential. The unlikely pioneers of this technique for funding music was the progressive rock band Marillion which, as Michael Lewis recounts in his 2002 book The Future Just Happened, mobilised their on-line fan club to raise money for a US tour and a new album. From this germ of an idea, the crowdfunding industry has continued grow at a rapid rate, although platforms dedicated to rewards and donation are now very much overshadowed by platforms that provide services akin to the mainstream financial sector. Nevertheless, crowdfunding can be an important source of funds to cash strapped musicians, and it is instructive that the largest number of funded projects on the Kickstarter platform, perhaps the best known rewards and donation focused crowdfunding site, is for music projects. Thus, of the almost 100,000 projects successfully funded via platform the largest category (22%) is music-related. The appetite for funding musicians for non-financial rewards was also confirmed by the fact that music-related projects on Kickstarter were more likely to raise funding than not, the only one of 15 categories of funding to have this positive balance. If one digs down into projects on sites like Kickstarter then it reveals that artists ask for funding to pay for the kinds of things that record companies once paid for through record deals, which they are more reluctant to offer in the current operating environment. Crowdfunding campaigns seek money to pay for recording, mixing and mastering of new songs, album artwork design, the manufacturing and printing of CDs, promotion and publicity, and website design. Other benefits are claimed to flow from this method of raising investment. For example, at a London-based industry event that I attended in 2013, Kendel Ratley, VP of Communities at Kickstarter, argued that crowdfunding sites were not only useful sources of cash but also of market intelligence: “Artists can learn from earlier campaigns about raising money”, she argued. “How am I going to tell my story, how am I going to represent myself to my fans. One campaign produces data on what works and what doesn’t”.

A third source of revenue is to convert fan-enthusiasm into income that goes beyond the traditional means of selling sound recordings or concert tickets. One option is to enter into a brand partnership with another company, one that wishes to trade on the image and audiences that artists have already constructed, effectively buying their endorsement. While many of these deals are successful, and can give artists a useful injection of cash, they can on occasion go spectacularly wrong as brands collide. For example, consider the deal between Apple and U2 where the latter agreed that the release of their 2014 album, Songs of Innocence, could, in return for a fee, be distributed as a free product through iTunes to help promote the launch of the iPhone 6. However, while initially lauded by media commentators, such was the negative reaction by iPhone users to the unexpected and unasked for appearance of U2 songs in their iPlayer catalogues that less than a week after the launch Apple were forced to release a U2 removal tool, followed by an apology from the band, admitting that “we got carried away with ourselves”. Quite simply, for every U2 fan that welcomed the free music, there were many more ‘anti-fans’ that took exception to what they saw as the corruption of their digital music catalogues. An alternative way to capitalise on fan enthusiasm is to turn to crowdfunding platforms, where artists can raise money for ‘projects’ by offering not a return on investment but some kind of reward, which might be material or experiential. The unlikely pioneers of this technique for funding music was the progressive rock band Marillion which, as Michael Lewis recounts in his 2002 book The Future Just Happened, mobilised their on-line fan club to raise money for a US tour and a new album. From this germ of an idea, the crowdfunding industry has continued grow at a rapid rate, although platforms dedicated to rewards and donation are now very much overshadowed by platforms that provide services akin to the mainstream financial sector. Nevertheless, crowdfunding can be an important source of funds to cash strapped musicians, and it is instructive that the largest number of funded projects on the Kickstarter platform, perhaps the best known rewards and donation focused crowdfunding site, is for music projects. Thus, of the almost 100,000 projects successfully funded via platform the largest category (22%) is music-related. The appetite for funding musicians for non-financial rewards was also confirmed by the fact that music-related projects on Kickstarter were more likely to raise funding than not, the only one of 15 categories of funding to have this positive balance. If one digs down into projects on sites like Kickstarter then it reveals that artists ask for funding to pay for the kinds of things that record companies once paid for through record deals, which they are more reluctant to offer in the current operating environment. Crowdfunding campaigns seek money to pay for recording, mixing and mastering of new songs, album artwork design, the manufacturing and printing of CDs, promotion and publicity, and website design. Other benefits are claimed to flow from this method of raising investment. For example, at a London-based industry event that I attended in 2013, Kendel Ratley, VP of Communities at Kickstarter, argued that crowdfunding sites were not only useful sources of cash but also of market intelligence: “Artists can learn from earlier campaigns about raising money”, she argued. “How am I going to tell my story, how am I going to represent myself to my fans. One campaign produces data on what works and what doesn’t”.

Navigating the new music industry landscape

In making this argument, Ratley was in effect prefiguring the arguments that would be made to me two years later on the other side of the world by Lynn Robnett. The music industry is in many ways a flatter, more open and more contestable market than hitherto which, through the emergence of various platforms and practices such as crowdfunding, social media, and streaming, provide data and information to artists and their management if they are able to parse meaning and understanding to search out new audiences and opportunities. But not all artists will have the skills and confidence to be able to navigate this new music industry landscape, and which will have equity implications. And in some respects, the new music industry looks much like the old music industry, only that there even fewer global music companies, which has intensified its tendency towards oligopsony. Moreover, as the share of income from streaming confirms, the balance of power still lies with companies and not the artists.

But despite all this, there is no shortage of new music – quite the reverse in fact – and it seems clear that many are still attracted to the idea of a professional musical career, despite the difficulties and obstacles. The key problem is making music pay, and given the scaling back of the welfare function once provided by record companies through multi-album deals and advances that were only ‘recouped’ from sales, it is an even more precarious venture. As a fan of new music, and one who has developed quite a complicated automated search process to uncover such music through subscriptions to various music sites to obtain interesting and unusual tracks, I hope innovative and talented people continue to be attracted to musical careers. But the advice I would offer is make sure you get good management and be cautious about giving up the day job.

By Andrew Leyshon, Professor of Economic Geography

[1] I was in Melbourne thanks to a University of Melbourne Eminent Visiting Scholar Research Grant, which allowed me to be based in the Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Business and Economics, for four weeks during October 2015. I am particularly grateful to the University of Melbourne for making the trip possible, and for colleagues there for making the visit so enjoyable. I am especially grateful to Dr Erica Coslor who first suggested the scheme, which facilitated joint research on the high value art market.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply