03/12/2024, by aezcr

Fishing for solutions: the place-name Stronsay

Stronsay occurs several times in the various manuscripts containing the Saga of the Earls Orkney (Orkneyinga Saga). The name occurs as Straumsey Streaumsey, Striansey, Striensø, Strionsey, and Strionsø. The last element is ON ey ‘island’, common in Orkney place-names. What then of the first element? In 1915 Magnus Olsen proposed that Norwegian place-names containing the ON element strjón may have a comparable meaning to that of OE streon with the sense ‘gain, profit, wealth’. In this analysis, which focused on the region of Stavanger in Norway, Olsen interpreted this term as relating to a rich catch, to fishing in particular, and in the discussion he included the Orkney name Stronsay as an example (Rygh, 1915: 72).

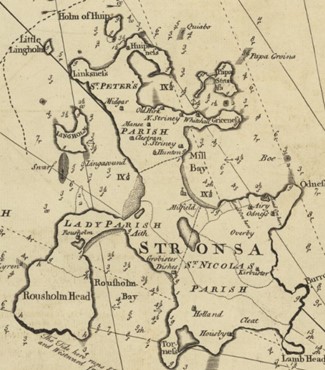

In the 1920s Hugh Marwick was inclined to follow Bede’s rendering of the name for Whitby (Northumberland) Streanaeshalch, which contains the OE element streon, and which he interpreted as ‘beacon bay’ (Marwick, 1926–27: 73). Johnson, in the 1930s, thought that it might be ‘star shaped island’ from ON stjarna but this interpretation has not gained much traction despite appearances (see map below) (Johnson, 1934: 304). In his Orkney Farm Names, some thirty years after putting his initial thoughts down on the Stronsay name, Marwick leant much more towards Olson’s understanding of a place of rich fishing, which seemed fitting since ‘for centuries the island has been famed for its herring fishing (Marwick, 1952: 23). We cannot rule out other origins of the ‘wealth’ associated with the island, agricultural for example, but Marwick’s conclusion, or we should perhaps better say Olsen’s, has since been followed by Carole Hough who showed that ON strjón is unattested outside place-names and that it, along with OE (ge)strēon, were words with a common ancestor indicating profit, wealth. Thus, if we follow Olsen and Marwick we are left with a meaning for Stronsay from ON strjón–ey, ‘island of good/rich fishing’. This aligns with Olsen’s original understanding, as well as that which Hough applies to give the old name for Whitby, Streanaeshalch a similar meaning (Hough, 2003: 21).

Detail from MacKenzie’s map of the north east coast of Orkney showing of Stronsay (1750). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Fishing has long played an important role in Orkney, and we get a lovely illustration of fishing in the saga. In Chapter 85 there is a fine description of fishing practices, where we hear of Earl Rǫgnvaldr in Shetland who came across an

‘old householder and asked why he was not rowing out to the fishing as other men. The householder says his crew had not arrived. ‘Householder’, said the cowl-man, ‘do you want me to row out with you?’ ‘I want that,’ says the householder, ‘and yet I want to have the share that belongs to my ship, because I have many children at home and I work for them as much as I am able.’ Then they rowed out past Sumburgh Head and landward of Horse Island. There was a strong current where they stopped, and big eddies; they were going to sit in the eddy and fish from the roost. The cowl-man sat in the bow and held the boat with the oars and the householder was to fish’ (chapter 85).

This passage is illustrative of how fishing was organised, at least on this occasion. The scale was small, and neighbours fished together – in this extract a crew of two sit in the eddy of a strong current off the southern tip of Shetland. Later, after further adventures which tell us how they were pulled by the current into dangerous waters, we hear of how the catch was brought in:

They rowed to land and pulled up the boat, and the householder asked the cowl-man to divide the fish. But the cowl-man asked the householder to divide it as he liked, said he did not want to have more than his third share. Many people had come to the beach there, both men and women, and many poor folk. The cowl-man gave the poor people all the fish he had been allotted during the day, and then prepared to leave. It was necessary to go up a bank, and many women were sitting on the bank (chapter 85).

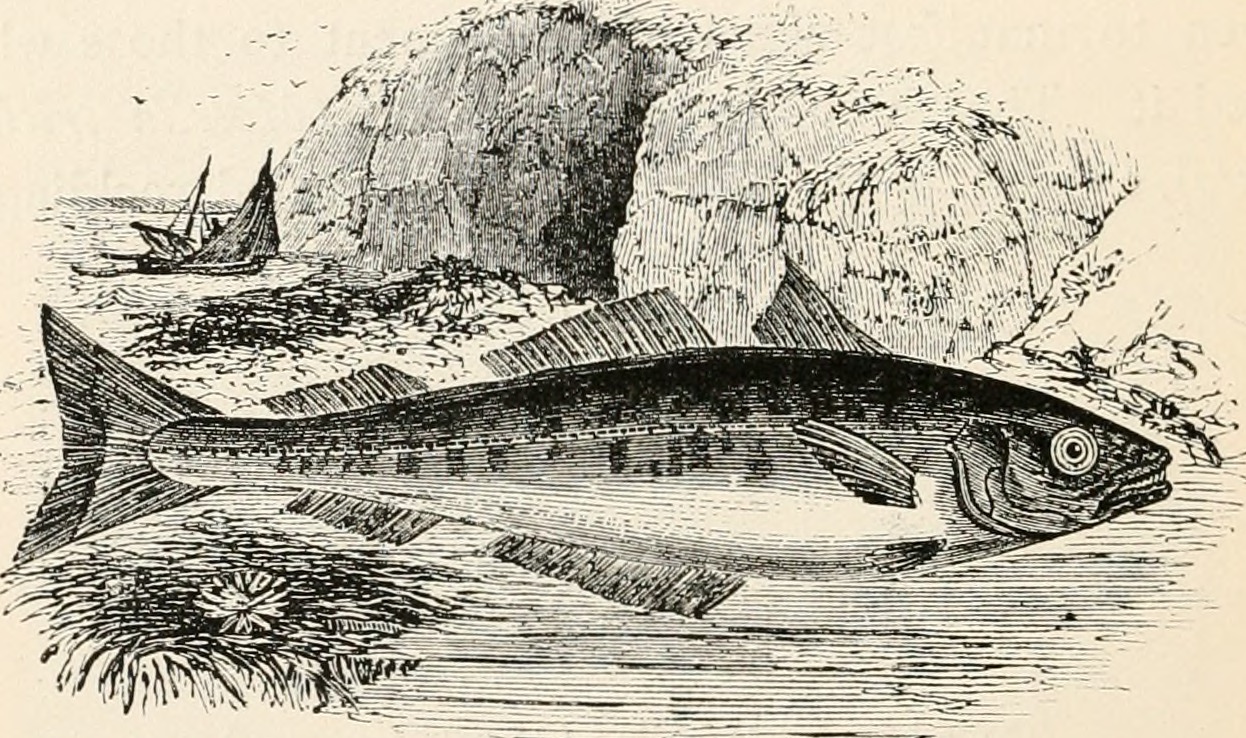

Image of a coal fish ‘to the inhabitants of the Orkney Islands its young are the chief food’. Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

Although ostensibly about Earl Rǫgnvaldr, this chapter offers us some insights into the importance of fishing to the inhabitants of Orkney and Shetland and some of those fishing practices: how the catch was landed and the boat drawn up onto a beach. We can assume, from later practices, that the catch may have been eaten fresh, but equally it may have been dried and salted as an essential staple for the winter months. Local consumption of fish may also have been complemented by the export of cured fish beyond Orkney’ (Barrett, 1997: 616–638).

Indeed, it seems that it was during the Viking Age, in the period between 850–950, that fish consumption increased significantly in Orkney (Barrett, 2004: 249–271). This, then, is perhaps the period during which Stronsay was named. Knowing that an island was good for fishing would have been valuable information, and that it was a place renowned for its natural resource may explain why it attracted a name meaning ‘island of good fishing’ just at the point when local consumption, and even trade, were beginning to increase.

Matthew Blake and Corinna Rayner

Further Reading

Barrett, James H., ‘Fish Trade in Norse Orkney and Caithness: a zooarchaeological approach’, Antiquity, 71:273 (1997), pp. 616–638.

Barrett, James H., ‘Identity, Gender, Religion and Economy: New Isotope and Radiocarbon Evidence for Marine Resource Intensification in Early Historic Orkney, Scotland, UK’, pp. 249–271, European Journal of Archaeology 7: 2004.

Hough, Carole, ‘Strenshall, Streanaeshalch and Stronsay’ JEPNS, 35 (2003) pp. 17–24.

Johnson, James. B., Place-names of Scotland (London: J. Murray, 1934).

Marwick, Hugh, ‘Antiquarian notes on Stronsay’, Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society, V (Kirkwall: Orkney Antiquarian Society, 1926–7).

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

Rygh, Oluf, Norske Gaardnavne: Stavanger AMT X, 10th edition. Re-edited by Magnus Olsen (Kristiania: W. C. Fabritius & sønners, 1915).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply