15/07/2024, by aezcr

Cairston: a strategic place?

There are three Cairstons in Orkney all in close proximity to each other, the modern settlement so-named near Stromness on Orkney’s west Mainland, Cairston Roads offshore near Inner and Outer Holm, and Bu of Cairston on the coast of the Bay of Ireland. Cairston occurs twice in the Saga of the Earls of Orkney and it is the Bu of Cairston which is considered to be the original settlement associated by Finnbogi Guðmundsson with Kjarreksstaðir in his edition of Orkneyinga saga.

View towards the Loch of Stenness from Cairston Bu on the coast of the Bay of Ireland.

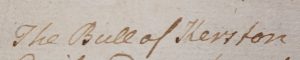

The place-name occurs as Kiarrexstauþum/Kiarreksstauþum in the AM 325 II 4to (ca. 1290–1310) manuscript and as Kiareksstodum in Flateyjarbók (1387–1394). Later forms of the name include Bull of Kerstane (1492), Karstane (1500), Kairstane (1595), and Cairstane, Cairsten (1614) (Marwick, p. 162).

‘Bull of Kerston’ in the MacKenzie manuscript, 1750, Orkney Archives, D8/5.

Marwick interprets the first element as an otherwise unattested ON personal name, Kjarrekr, which may be formed by adding the common suffix –rekr to the ‘early’ personal name Kjárr, giving ‘Kjarrekr’s stead’ (Taylor, p. 43). The Kiárr name apparently comes from a noble family, ‘af ǫðlinga ætt’ (Lind, p. 688), but the element itself was not interpreted by Lind, Taylor, or Marwick. Since the presence of the –rekr suffix indicates a personal name, the consideration of other specific elements such as kjarr ‘thicket, scrub’ (ONP), which occurs frequently in place-names, and kjarr a ‘kind of bird, a curlew(?)’ (Cleasby & Vigfusson) is negated.

The second (generic) element, the habitative ON staðir, is covered extensively in the discussion of Knarston, so won’t be touched on in great detail here beyond commenting that, in place-names, it is generally interpreted as ‘farm-settlement/dwelling’. On occasion, however, when the context is appropriate, it may be the case that this ending derives from ON stǫð ‘landing place, boat place’ (ONP), and it is the context of the saga, the geography of the place, and archaeological evidence that will determine which of the two is the more likely.

The saga context is that Sveinn Ásleifarson and Earl Erlendr, in response to King Eysteinn [Haraldsson of Norway, 1142–57] saying that Erlendr should have ‘that part of the Orkneys which Earl Haraldr had previously had’, decide to go and meet with Haraldr to ‘ask him to give up his territory’, and in so doing meet him ‘offshore from Cairston’ where he was ‘anchored’. On seeing Erlendr and Sveinn approach on their longships Haraldr and his men fled into the castle ‘which was there then’. The description of how they met fyrir ‘along (the coast/beach)’ at Cairston where Haraldr lá … á skipum, ‘lay on ships’ gives some weight to an ON stǫð ‘landing place, boat place’ interpretation.

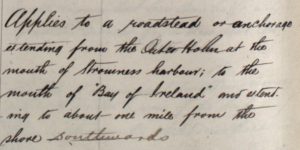

Whether they were anchored offshore or were laid up along the beach near Cairston is debatable, fyrir and lá can imply both senses. However there is, nearby, an area of sea named ‘Cairston Roads’ so called because, according to the Ordnance Survey (OS) name book entry, it applies ‘to a roadstead or anchorage extending from the Outer Holm at the mouth of Stromness harbour; to the mouth of the “Bay of Ireland” and extending to about one mile from the shore southwards’. ‘Roads’ here, then, has the sense of being a nautical highway, a ‘place where ships ride’, or a ‘sheltered piece of water near the shore’, ‘place where vessels may safely lie at anchor’ (OED).

Following their encounter Haraldr swore ‘an oath that Erlendr should have his part of the islands and he should never make a claim on this territory against him’. Despite his oath, Haraldr later returned with ‘four ships and one hundred men’ and after various incidents took some men including Arnfinnr, the brother of Anakol, hostage before returning to Thurso. Arnfinnr was taken to Lambaborg and ‘would only be released if Earl Erlendr and Sveinn let them have the ship that they had taken off Cairston’. The sense here seems to be that Erlendr and Sveinn captured one of Haraldr’s ships from where it was laid up, after they fled up to the castle, again resonating with a –stǫð interpretation for this place-name.

The ‘castle’ that Haraldr and his men flee to ‘which was there then’ once they’d laid up, or perhaps just abandoned their ships, is rendered kastalann ‘castle, fortress, citadel’ in the saga. The wording has attracted some discussion about whether it was there or not at the time of the incident, or simply remembered. Although ‘there is no confirmed archaeological evidence for Norse remains, it is in little doubt that a high-status settlement once occupied the site’, perhaps ‘similar to several others found in Orkney, including Tuquoy in Westray and the Bu in Orphir’ (Stevens et al., p. 374). The transition from kastalann to bú is perhaps reasonable then since the oldest farms with the root word bú are the high-status farms in Orkney which had often been the residence of earls (Huser, p. 27).

Detail from Bellin’s Carte des principaux ports des Isles Orcades, 1757, showing buildings at Cairston and an anchorage offshore. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Thomson observes that ‘Bu of’ places often continue to exist as large farms occupying prime sites ‘located at low altitude in the arable heartland in very markedly coastal positions… used for the principal properties of the earls of Orkney’, and this certainly seems to fit with Cairston. This may in turn support a –stǫð rather than –staðir interpretation since, with a couple of exceptions, Orkney ‘places with staðir-names tend to be located in inland arable districts at a comparatively low altitude, and are mainly concentrated in the interior lowlands of West Mainland’, the exceptions being Knarston (Rousay, North Isles) and Herston (South Ronaldsay, South Isles) (Marwick, p. 235). Cairston, however, cannot be said to be ‘inland’, and nor can Knarston – the two locatable saga ‘staðir’ names.

The location of Cairston is significant. It commands a strategic point ‘with undeniable importance as a base for incoming shipping and for controlling access to the interior of the West Mainland’ (Crawford, p. 34).

Images showing Cairston’s strategic position with views north towards the Loch of Stenness (L) and south through the Bay of Ireland (R).

Additionally, there ‘is a Wart’, ON varða ‘beacon’, near Brig of Waith, ON eið ‘isthmus’, ‘exactly where a warning beacon or signal would prove helpful to seamen navigating the narrow, and shallow channel between the Loch of Stenness and the open waters of the Bay of Ireland’ (Bates et al., p. 34). Significantly, the name ‘Wart’ is a ‘shore name’ that may signify ‘an ancient mustering place for the local levies’ (Bates et al., p. 34).

Detail from MacKenzie’s map of Orkney (1750), showing the location of Cairston (Kerston Bue), the Brig of Waith marked ‘Bridge’, an anchorage offshore denoted by an anchor symbol, and a clear strategic command over the Bay of Ireland route into the Loch of Stenness. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

In summary then, while Cairston can be interpreted as ‘Kjarrekr’s stead’, there is perhaps more evidence for it to be interpreted as ‘Kjarrekr’s boat stances/landing places’. While it occurs in the saga in the dative plural form, in which both –staðir and –stǫð are identical and so equally plausible, the context provided by the saga references ships anchored offshore or laid up along the beach. The geographical location, too, with its commanding position overseeing the comings and goings from the Bay of Ireland to the Loch of the Stenness made Cairston a place of strategic importance which formed, together with the Brig of Waith and the nearby Wart, a series of defensive positions. As a landing-place on the earl’s estate it was in effect the ‘front door’ and a place from which to disembark at a protected and significant routeway extending inland up to Birsay, and this made the boats stances here significant enough to give their name to the estate.

Corinna Rayner and Matthew Blake.

Further Reading

Bates, C. R. et al. ‘The Environmental Context of the Neolithic Monuments on the Brodgar Isthmus, Mainland, Orkney’, Journal of archaeological science, reports 7 (2016), pp. 394–407.

Bates, Martin, Richard Bates, Barbara Crawford, and Alexandra Sanmark, ‘The Norse Waterways of West Mainland Orkney, Scotland’, Journal of wetland archaeology, 20 (1–2) 2020, pp.25–42.

Crawford, B. E. 2006, ‘Huseby, Harray and Knarston in the West Mainland of Orkney: Toponymic Indicators of Administrative Authority?’, in Names through the Looking-Glass, ed. by P. Gammeltoft and B. Jørgensen (Copenhagen: C. A. Reitzels Forlag A/S, 2006), pp. 21–44.

Guðmundsson, Finnbogi. Orkneyinga saga ; Legenda de Sancto Magno ; Magnúss saga Skemmri; Magnúss saga Lengri; Helga þáttr ok Úlfs (Reykjavík: Hið Íslenzka fornritafélag, 1965).

Huser, Thomas Marcus, ‘Fra ‘Færevåg’ til ‘Pier of Wall’? Eldre bebyggelsesnavn på Westray, Orknøyene’ (unpublished dissertation, University of Oslo, 2008).

Lind, E. H. Norsk-isländska dopnamn ock fingerade namn från medeltiden (Uppsala: Lundequistska bokhandeln, 1905).

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

Sandnes, Berit, From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney (Scottish Place-Name Society, 2010).

Stevens, Tim, Melissa Melikian, Sarah Jane Grieve, ‘Excavations at an early medieval cemetery at Stromness, Orkney’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 135 (2005), pp. 371–393.

Taylor, Alex B., ‘Some saga place-names’, Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society, 9 (1930-1931), pp. 41–45.

Thomson, William P. L., Orkney Land and People, (Kirkwall: Kirkwall Press, 2008).

This is a wild stab promoted by your reference to Bay of Ireland and memory of Sigurd’s Christmas visit to offer his mum Gormlaith in exchange for help at Clontarf but is there any possibility at all that the first element could be Irish cíar -used as first element for people names like Ciarraige but also an adjective meaning dar or gloomy?

See edil (electronic dictionary of (Old) Irish). ? I know that there is very little Gaelic in Orkney world so I appreciate that I’m reaching here but I’m just wondering if Kjarrrekr could be a hybrid personal name.

Cathy Swift

If this is a coastal site I think it might be worth considering whether this was once Kjarrekastaðir, incorporating ‘reki’.