26/11/2024, by aezcr

Egilsay: Earls, Churches, and Island(s)

Egilsay is a relatively small, carrot-shaped island which lies around 19 miles north of Kirkwall, Mainland. The island forms one of the Inner North Isles, alongside Wyre and Rousay, and is connected to both islands and Tingwall, Mainland by ferry.

Though not mentioned exceptionally frequently in Orkneyinga saga, appearing only six times, Egilsay provides the location for one of the most compelling episodes in the saga: the death of Earl Magnús at the hands of Earl Hákon. Chapter 47 notes that ‘the reconciliation agreement between them was to be in the spring in the Easter week on Egilsay’. And though ‘Earl Magnús arrived first in Egilsay with his troop’, it becomes clear that treachery, rather than reconciliation, is Earl Hákon’s aim. Magnús is captured during his prayers by Hákon. Despite reportedly offering several alternatives to his death including pilgrimage to Rome or Jerusalem, exile in Scotland, and permanent imprisonment, Magnús is killed by a blow to the head on the orders of Hákon around 16th April 1117. Bishop William of Orkney sanctified Earl Magnús in 1136, and it is thought that St Magnus Church on Egilsay was likely constructed shortly after on the spot where the murder of Magnús is said to have taken place (HES, 2016).

St Magnus Church, Egilsay, with Rousay visible in the background © Tom Fairfax.

Initially, the etymology of the place-name appears somewhat clearcut, with the first element comprising the ON personal name Egill in the genitive form. The final part or element of this name is the well attested ON ey ‘island’, which securely forms the generic element of several Orkney islands as well as the name Orkney itself. This etymology would follow an established pattern of personal name + ON ey ‘island’ in Orkney – such as Hrólfsey (Rousay), Gáreksey (Gairsay), Kolbeinsey (Copinsay) – and parallel the accepted origin for Egilsay in Shetland (Stewart, 1987: 6). The early spellings of Egilsay which feature in the saga are relatively stable, with only the ending changing as appropriate e.g. i Egilsey, udi Egilsø, til Egilseyiar. In this view, the first element of Egils– seems well supported.

An alternate reading of Gaelic eaglais ‘church’ deriving from Old Irish eclais and Latin ecclesia has been suggested mainly due to the belief that St Magnus Church, the dominating feature of the island, was pre-Norse (Munch 1860 cited in Marwick, 1952: 71). This has been disproven, and after St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, the church on Egilsay can be considered ‘the finest surviving Norse church in Scotland’ (HES, 2016). The archaeological report of the site consolidates this, and suggests that the existing structure dates from nearer the end of the 12th century (RCAHMS, 1946: 228). However, studies indicate that a church existed on the site prior to the current structure and Ritchie posits that the current church replaced the previous one in which Magnús was killed (Ritchie, 1996: 103-4; Canmore, n.d). This presence of a church on Egilsay which predates St Magnus church is evidenced in Orkneyinga saga. In Chapter 48, Magnús ‘went into the church for prayer’ upon the arrival of Hákon; in Chapter 49 Hákon’s men ‘ran first to the church and searched it’; and in Chapter 51 Hákon ‘did not allow the earl to be carried to the church’.

If the extant church does not pre-date Magnús’ sanctification but a church is repeatedly mentioned on Egilsay at the time of Magnús’ death, it seems highly likely that a different church occupied the site prior to the construction of St Magnus Church.[1] Perhaps it is this original church which could have been pre-Norse in origin, accounting for the descriptive use of Gaelic eaglais rather than ON kirkja. Though the use of eaglais could reasonably reflect a Gaelic loanword used by Old Norse speakers, the volume of Papar names e.g. Papa Westray, Papa Stronsay, Papdale, Steven of Papay (see also Papar of Papey blog) in Orkney evidence pre-Norse ecclesiastical activity in the islands, some of which could be Irish or Irish-influenced.[2] It seems feasible that such ecclesiastic prominence in the islands could leave influence beyond the Papar name element and result in other lingering Gaelic lexemes in Orcadian island names, especially ones also associated with religious life. Consequently, the etymological argument for ‘church island’ from Gaelic eglais and Old Norse ey regains credibility, or at very least feasibility. This interpretation is strengthened by three further factors: the longstanding connection between Egilsay and the Bishops of Orkney, Egilsay’s neighbour Kili Holm, and historical forms of Egilsay found in Scottish documents.

Map of Papar names (red) with potential ecclesiastic Gaelic-Old Norse names (green) Egilsay, Kili Holm, and Kirk and Kill o’Howe.

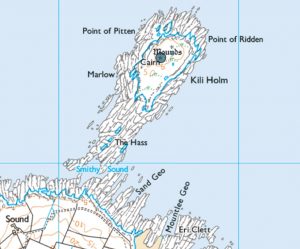

Firstly, Orkneyinga saga contains several references to Bishop Vilhjálmr of Orkney living on Egilsay, holding services and meetings there, and it appears that prior to the construction of the Bishop’s Palace in Kirkwall the bishop resided on Egilsay, at least for some of the time.[3] This demonstrates a connection between Egilsay and the church prior to the construction of St Magnus Church in the late 1100s. Secondly, Kili Holm is a small tidal islet connected to Egilsay and derives from cille, the genitive form of Gaelic ceall ‘monk’s cell’ from Latin cella, and ON holmr ‘islet’ (Marwick, 1952: 71). While Old Norse kíll ‘brook, tributary, narrow inlet’ – as evidenced in Scottish names such as the Kyles of Bute – theoretically could form an alternate etymology, the topography of the Egilsay/Kili Holm sound makes this more unlikely. However, the same element can be found on a chapel site named Kirk and Kill o’ Howe in Sanday, where two churches occupied neighbouring hill summits (Marwick, 1923: 256; Lamb, 1980: 8). Here there is more secure evidence of Gaelic name elements being used alongside Norse, especially in association with ecclesiastical practices. If Kili Holm and Kirk and Kill o’ Howe can be taken to provide onomastic evidence for Gaelic-Old Norse dual language compounds in the geographic area around Egilsay, perhaps this strengthens the argument for Egilsay itself being a Gaelic-Norse compound which indicates the religious activities in Orkney that pre-date extensive Norse settlement.

Kili Holm connected to the north of Egilsay by Smithy Sound. Ordnance Survey Map.

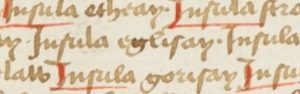

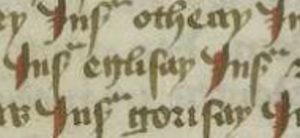

Thirdly, despite the stability of Egilsay’s spellings in manuscripts of Orkneyinga saga, several variant spellings can be found across historic Scottish documents. While these spelling variants lend support to eaglais rather than Egill, the possibility that Scottish writers unfamiliar with Old Norse personal names may have reinterpreted the name to a more familiar Gaelic name element must be noted. Nonetheless, in Bower’s 15th century chronicle, The Scotichronicon, Egilsay is written as Eglisay. This spelling also features in two variant manuscript forms of John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum: Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Codex Helmstedt 538 and Cambridge, Trinity College MS O. 9. 9.

: Egilsay spelling variation eglisay in Cambridge, Trinity College MS O. 9. 9. fol 21r.]

Egilsay spelling variation eglisay in Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Codex Helmstedt 538. fol 25r.]

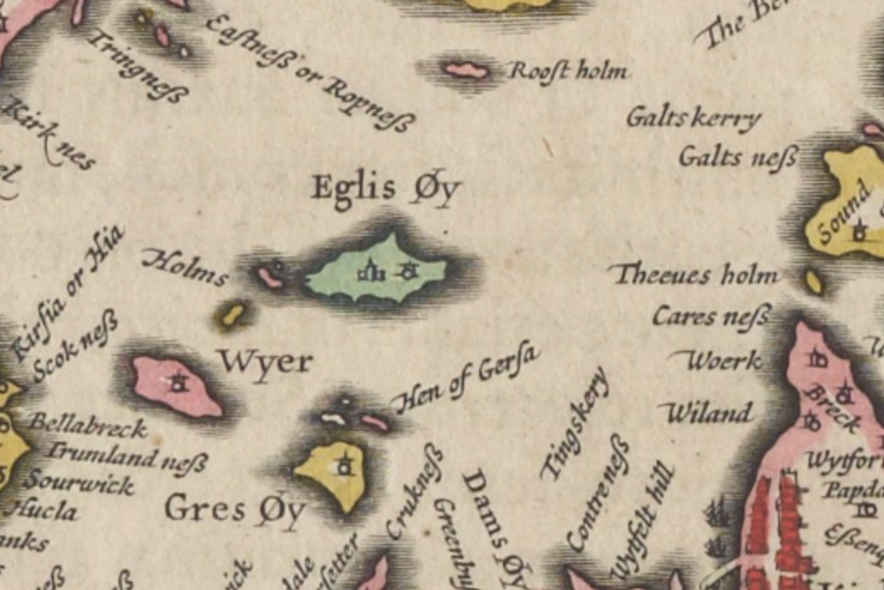

Interestingly, a mid-17th map by Robert Gordon also records the island as Eglis Øy. These spelling variations across Scottish documents and historical recordings all indicate Egilsay in a metathesised form from its modern spelling. But, by the time of the Orkney OS Name Books, 1879-1880 these forms appear to be lost, as only Egilshay and Egilsay are recorded. The early Scottish spellings provide reasonable linguistic evidence supporting eaglais ‘church’ as the specific element of Egilsay.

Detail from the 1654 map of Orkney by Willem Janszoon Blaeu and Joan Blaeu.] Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

On a final note, Egilsay appears to be ideally situated between several of the Papar islands, as well as the Þing site on the Mainland of Orkney. Theoretically the island could reasonably provide a suitable rest or meeting point between these places, or indeed function as part of a wider pre-Norse ecclesiastic network. Perhaps then, on the whole, the evidence suggests the importance of the island in relation to religious communities in Orkney, thus restoring Gaelic eaglais as a strong potential candidate in the etymological origin of Egilsay.

Em Horne

Further Reading

‘Egilsay, St Magnus Church’, Canmore. <https://canmore.org.uk/site/2697/egilsay-st-magnuss-church>. [Accessed 18.10.2024]

John of Fordun‘s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O. 9. 9.

John of Fordun‘s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Codex Helmstedt 538.

Lamb, R G., Sanday and North Ronaldsay: An Archeological survey of two of the North Isles of Orkney. Edinburgh: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotand, 1980.

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm-Names. Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952.

Marwick, Hugh. Celtic Place-Names in Orkney, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 57, 1923: 251–265.

Orkney Volume 16, OS1/23/16/182. <https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/orkney-os-name-books-1879-1880/orkney-volume-16/182>. [Accessed 18. 10. 2024].

RCAHMS, The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Twelfth report with an inventory of the ancient monuments of Orkney and Shetland, 3v. Edinburgh: HMSO, 1946.

Ritchie, Anna, Orkney: Exploring Scotland’s Heritage. Edinburgh: The Stationary Office, 1996.

Stewart, John, Shetland Place-Names. Lerwick: Shetland Library and Museum, 1987.

“St Magnus Church: History”. Historic Environment Scotland. 2 December 2016. <https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/st-magnus-church-egilsay/history/>. [Accessed 18.10.2024].

Watt, D.E.R. with A Borthwick (eds.), Scotichronicon by Walter Bower in Latin and English, Volume 2. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1998.

[1] This replacement of a new church on an old church site was not uncommon in twelfth century Scotland, with similar instances occurring at St Andrews Cathedral; St Serf in Culross, Fife; Dunfermline Abbey, and potentially Glasgow Cathedral.

[2] St Findan is noted for roaming an island, potentially Papay, for several days before encountering the Bishop who spoke Irish and had been educated in Ireland (Omand, 1986: 284-287).

[3] Thanks to Tom Fairfax for discussions on this. Results of this work with Historic Environment Scotland are yet to be released.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply