16/11/2024, by aezcr

Kolr Kalason, the forgotten hero of The Saga of the Earls of Orkney

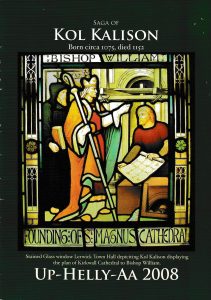

Working in the Orkney Archive not long ago, I came across an intriguing booklet called The Saga of Kol Kalison, about the Norwegian father of the twelfth-century Earl of Orkney Rǫgnvaldr Kali Kolsson:

Saga of Kol Kalison booklet, by Charles Grant.

The author, Charles Grant, kindly sent me the following information about it:

The book was written for the Jarl Squad 2008 Lerwick Up-Helly-Aa festival. The tradition is that the Jarl or head guizer picks a Viking to represent and his squad makes a Viking costume picking various items out of the Saga.

The Saga of Kol Kalison was so interesting that Roy Leask the Jarl and me decided I would do a full version to give to every squad member …

The booklet begins thus:

This year’s Guizer Jarl Roy Leask has chosen to represent Kol Kalison because in common with many of his squad they work in the local construction industry and Kol was a builder.

First page of the ‘Saga of Kol Kalison’ booklet.

Roy, Charles and the builders of Lerwick have thus given Kolr Kalason (to give his name in its Old Norse form) more attention than most scholars of Orkneyinga saga. Following in their footsteps I suggest here that Kolr was a more important character than previously recognised. Certainly, both the saga and modern scholars credit him with the vision of building St Magnus Cathedral. But a close reading of the saga shows that he was also the main force behind his son’s ascent to the earldom more generally.

Colour photograph of St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall. © Judith Jesch.

Kolr’s family

Kolr’s story begins with his father Kali Sæbjarnarson, ‘a great sage and dear to the king and skilled at poetry’. Father and son are said to have accompanied the Norwegian king Magnús Bare-legged on an expedition which culminated in the battle of the Menai Strait. They are not mentioned in other accounts of this well-documented voyage, so straightaway there is a sense of a particular tradition associated with this family.

When Kali dies as a result of injuries received in the battle, King Magnús compensates his son Kolr with an Orcadian wife, Gunnhildr Erlendsdóttir, thus introducing another branch of Rǫgnvaldr’s family tree. Gunnhildr was the sister of the later saint Magnús Erlendsson and his brother Erlingr, both of whom were also in the battle. The saga says Erlingr died there and highlights a discrepancy with Snorri Sturluson’s account, which instead has him die with Magnús Bare-legged in Ulster on a later expedition. Again, we sense a particular family tradition at odds with other Norse historiography.

Kali Kolsson, the later Rǫgnvaldr, is then introduced in a charming picture of a happy family:

Kolr Kalason became a landed man of the king and went east to Norway with the king and home to Agder with his wife and settled down on his estates. Kolr and Gunnhildr had two children; their son had the name Kali and their daughter Ingiríðr. Both of them were very promising and brought up with great love.

This is a further indication of a family history behind the saga’s account. The closeness of this small family unit is also indicated by the fact that Rǫgnvaldr later gave his daughter, his only surviving child, the same name as his sister.

Later the young Kali is given a glowing description:

Kali … was the most promising person, of medium height and well-formed, with strong limbs and light-brown hair; he was a very popular person and more skilful than most other people.

This is a standard saga-description focusing on notable and praiseworthy features, but as Kali matures, the need for Kolr’s guidance becomes clear. Although the saga does not say so explicitly, it is likely that when the fifteen year-old Kali joined some merchants on a voyage to Grimsby with ‘good merchandise’, he was kitted out for this formative experience by his wealthy father. Kali’s main achievement in Grimsby seems to have been to return from England with a taste for its latest fashions.

After a few years alternating trading voyages with stays in Norway, Kali requires further paternal assistance when a feud erupts between the followers of his friend Jón and his cousin Sǫlmundr. In their cups in Bergen, the followers get into an argument ‘as to who were thought to be the noblest of the landed men in Norway’. This leads to violence and then killings. Kali is involved out of loyalty to Sǫlmundr but he is also friends with Jón and accepts a settlement too quickly. Kolr is not happy and eventually prevails:

… it was decided as Kolr wished, with the stipulation that Kolr promised not to conclude this matter before Sǫlmundr had had what he deserved; Kolr was also to make all the decisions in the case.

He takes over, devising a cunning plan involving disguise and subterfuge. He also gets caught up in a fight which prolongs the dispute. There is no sign of Kali’s involvement. Ultimately, King Sigurðr steps in to bring it all to an end, with a reconciliation sealed by the marriage of Kolr’s daughter Ingiríðr to Jón. Almost as a non-sequitur, part of the settlement is that:

King Sigurðr gave Kali Kolsson half of the Orkneys together with Earl Páll Hákonarson and the title of earl with it … This part of the Orkneys had belonged to St Magnús, Kali’s mother’s brother.

In another titbit of family history, the king gives Kali his new name of Rǫgnvaldr. This name was suggested by his mother Gunnhildr, to commemorate an earlier ruler Rǫgnvaldr Brúsason, because, she said, ‘he had been the most effective of all the earls of the Orcadians’. This was hardly an auspicious choice, as Rǫgnvaldr Brúsason was killed by his uncle Þorfinnr Sigurðarson in one of the interminable feuds between close relatives that mark the Orkney earldom. From this distance all we can do is note that once again this detail suggests particular family traditions.

Conquering the earldom

Thus, Rǫgnvaldr Kali Kolsson’s early career is presented through the lens of family history. For a saga hero he does not appear to have been an underaged overachiever, in contrast to his great-grandfather Þorfinnr who was made an earl at the age of five and went on his first expedition at fourteen. Rǫgnvaldr’s conquest of the earldom inherited from his saintly uncle was very much driven by Kolr. It is Kolr who sends men to Orkney to ask the co-earl Páll Hákonarson to give up his half of the earldom. It is Kolr who forms an alliance with local power-brokers Frakǫkk and Ǫlvir. Rǫgnvaldr’s first expedition to the isles, supported by his friends Sǫlmundr and Jón, ends ignominiously. Back in Norway, Kolr consoles his son and takes it on himself to develop the next stage of the strategy, as well as provisioning ships for the expedition.

Rǫgnvald’s contribution is to call a meeting where he makes an impassioned, self-regarding and vague speech, reported only in indirect discourse:

Earl Rǫgnvaldr spoke about Earl Páll’s preparations and how much enmity the Orcadians had shown him when they intended to keep him from his patrimony which the kings of Norway had given him by right, and he gives a long and clever speech there and said that he intended to go to the Orkneys so as to acquire them or else die.

Rǫgnvaldr’s skills are rhetorical, and it is Kolr who is practical, and whose speech in response, much longer and given in direct discourse, moves things forward in a concrete way. He presents a well-worked out plan to seek the support of Saint Magnús and to build a ‘stone minster’ dedicated to him in gratitude. He already anticipates the future benefits of such a project:

… Kolr … said… ‘I want you to … have a stone minster built in Kirkwall in the Orkneys if you get that territory … and give money to it so that the town might develop, and that his holy relics and the bishop’s seat should move there.’

In subsequent events, Kolr is the one who gets round Páll’s beacon early-warning system on Fair Isle. Firstly he confuses the opponents with the clever trick of furling the sails at half-mast and then gradually raising them to make it look like his ships were approaching. He then installs his own man on Fair Isle to scupper the lighting of the beacon when they do approach for real.

Rǫgnvaldr is nowhere to be seen in any of this. It is only later that he starts to take a more active role, gradually winning over some of the most important people on the islands. Then Sveinn Ásleifarson comes on the scene and eliminates Páll Hákonarson, leaving the coast clear for Rǫgnvaldr to be sole earl. The question is raised whether this was done on Rǫgnvaldr’s instructions, but he is exonerated by no less than the bishop:

… the bishop straightaway went to meet Sigurðr and they discussed this news, and Sigurðr supposed that this must have been done at the behest of Earl Rǫgnvaldr. But the bishop answers that it would prove to be something other than that Earl Rǫgnvaldr had betrayed his kinsman Earl Páll. ‘I suppose,’ says the bishop, ‘that some others must have carried out this bad deed.’

The bishop then, together with Kolr and Sveinn Ásleifarson, manoeuvres to establish Rǫgnvaldr as the sole earl. In this impressive company, Rǫgnvaldr comes across as rather small fry.

Kolr then starts building the cathedral. He ‘was the great promoter of the building works and had most of the supervisory responsibility’. Kolr’s last gift to his son is to suggest an ingenious plan to make Orkney’s landholders buy their estates back from the earldom to pay for the construction. Rǫgnvaldr, ever the diplomat, modifies this plan to make it seem less harsh (though this appears to be more a matter of spin than substance) and the building continues, but Kolr is out of the saga.

Kolr statuette in St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall. © Judith Jesch.

This focus on Kolr has revealed a strand of material in the saga that is not centred solely on Rǫgnvaldr, but on his wider family, and especially on his father. Kolr is an indulgent father, training, advising, and pushing his beloved only son onto a political stage for which he might not otherwise have been particularly well suited. Rǫgnvaldr’s talents, such as they are, are rhetorical, rather than political or practical. Maybe he grew into the role, as the saga does occasionally present him as a bit of a diplomat. But it is not long before the wily bishops, together with Sveinn, make long-term plans, bringing in the young Haraldr Maddaðarson as co-earl. This hardly speaks of their confidence in Rǫgnvaldr as a ruler, and this picture is borne out twenty-two years later when Rǫgnvaldr is killed and Haraldr remains as sole earl. The chapter describing his killing suggests that his people were somewhat ambivalent about his qualities as a ruler. But when it came to writing the saga, the family traditions, emphasising the clever and resourceful Kolr, proved useful in glossing over the shortcomings of the young, inexperienced and probably quite frivolous Rǫgnvaldr. Further gloss was added when Rǫgnvaldr was declared a saint many years later, but that is another story.

Judith Jesch

Previous Post

‘Cancelled, no room to write’!No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply