05/10/2024, by aezcr

‘Hope’ of finding Viking harbours in Orkney…

We learn in the Saga of the Earls of Orkney that Sveinn Ásleifarson and Anakol sailed to Stronsay from Sanday and whilst there they ‘laid up by Huip Ness for some nights’ (ch. 92). Occurring as viþ Haufn, vid Hofn and viþ Hofsnes and vid Hofsnes in the saga manuscripts, it is thought that this place is Huip Ness in the north of Stronsay, although the actual location could be anywhere in the vicinity of the farm there called ‘Huip’.

While nes ‘a headland, a promontory’ is straightforward, huip needs a bit of thought. Marwick remarks that the Hofsnes forms are mistakes for ON hópsnes (Marwick, Farm Names, p. 25), that is, with hóp ‘a small landlocked bay or inlet, connected with the sea so as to be salt at flood tide and fresh at ebb’ (Cleasby & Vigfusson), presumably rather than hǫfn ‘place where a ship can moor, natural or constructed harbour, dockyard’ (ONP). Looking at the AM 325 I 4to manuscript forms the first occurrence appears as:

viþ haufn

And in its second occurrence as:

viþ Hofsnes

The ‘f’s and ‘p’s in this earliest manuscript, then, are rendered rather similarly, so a comparison with other ‘f’s and ‘p’s seems in order. For example, in the line above the first occurrence is the word fiandskaprs ‘hostility’ (ONP).

fiandskaprs

A comparison of the letter forms suggests that the first occurrence is hꜷfn, but the second is more difficult to discern. Interestingly the next earliest spelling of the place, in 1422, is Hupe. The document testifies to the fact that James Cragy dominus of Hupe ‘is a liegeman of the King of Norway, residing in Orkney’ (Storer Clouston, p. 34). That the estate was connected in some way to Norway may be a coincidence or it may be that it retained some of its status into the early fifteenth century.

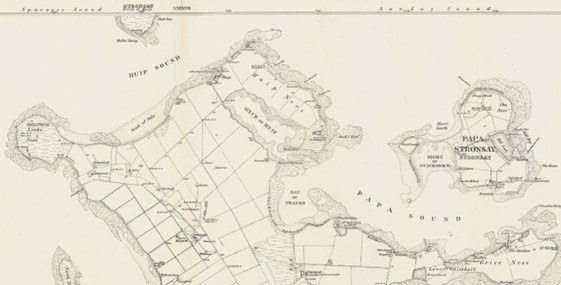

The precise spot to which Sveinn brought his boat is uncertain. There are a number of piers and slipways along the coast from the current Whitehall village (formerly Strenzie), one of Orkney’s best natural harbours (Marwick, Farm Names, pp. 27–45), for which the smaller island of Papa Stronsay provides shelter. This seems unlikely to be the place referred to in the saga as the farm of Huip sits some distance away on the north coast, so we must look elsewhere. MacKenzie’s 1750 map makes a point of showing places of safe anchorage and notably none are shown to the north of the farm around the Holm of Huip where we might expect to see one in connection with Huip Farm. The forms in –nes suggest that we need to look at what is now Huip Ness. If we look again at MacKenzie’s map at what is now the Oyce of Huip we can see a broad opening into the Bay of Franks and Papa Sound, but this is not the reality shown on the modern OS mapping (see below), nor is there any anchorage shown. However, there is little likelihood that the larger ships of the 1750s (when this map was drawn) would have used such a place given the depth of water and narrow entrance, rather they would have been at anchor gravitating to the facilities around Whitehall.

Detail from MacKenzie’s 1750 ‘North east coast of Orkney’ map. The red dot indicates the Oyce of Huip. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

If we return to the saga and look again at the wording, we read that ‘Sveinn and Anakol went to Stronsay and laid up by Huip Ness’ (Ch. 92) and that whilst ‘Sveinn was lying at Huip Ness, Earl Erlendr sailed there from out at sea’. The lying up may simply relate to the individuals resting at Stronsay, but it may mean that their boats were laid up there. That Erlendr later ‘sailed there from out at sea’ gives the impression that he was sailing into a smaller expanse of water from the sea. The Oyce of Huip, then, fits well with both senses: it is tidal and is a more-or-less closed bit of water giving safe harbour in which to lay up, and there is a sense of ‘entering’ into the space. It is the safest body of water away from the bigger seas to the east in the vicinity of Huip Ness.

Detail from the 1882 6 inch OS map showing the north end of Stronsay, sheet XCII.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

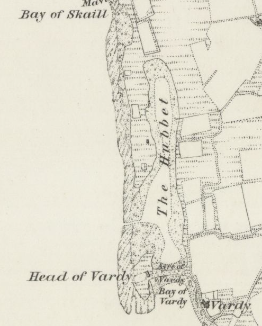

Does the term ‘huip’, then, indicate this type of geographical feature? For this it might be helpful to look at examples from further afield in Orkney. On the western side of Egilsay is the Hubbert and it, like the example on Stronsay, tallies nicely with Jakobsen’s definition of ‘a small, land-locked bay or creek formed by the sea and partly dry at ebb-tide’ (Jakobsen, p. 344).

Superficially at least the indications are promising. The Hubbert is a tidal pool that offers protection from the sea, albeit in shallow water. The Sites and Monuments Record for Orkney records that it:

‘is a naturally enclosed pool filling twice daily with the tides. A man-made channel approx 2m wide has been cut through the reef …. A large (cut c. 8m by 4m) naust can be seen on the thin grassed peninsular on the W side of the pool…Local information has it that this is the harbour is where St Magnus’ boats were taken ashore, and that he was murdered “aboot hands with Vardy”, rather than at the top of the hill where the church lies.’

Detail from the 1882 6 inch OS map showing the Hubbert on the west side of Egilsay, sheet XC. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

The Canmore record shows that the Hubbert’s natural harbour has been enhanced to make it more suitable to use for boats. Like the Oyce of Huip in Stronsay it is tidal. In landscape terms they both fit Jakobsen’s definition, and both have been used as harbours, but it is noteworthy that they are no longer in use today. There are other examples of enhanced natural features being used for this type of activity in Orkney, for example, Wheelies Taing in Papa Westray (see Pollard, Gibson & Littlewood, pp. 299–322). Another well-known example is that of Kirkwall which was, for most of its history, tucked against the edge of the Peedie Sea.

Detail from MacKenzie’s 1750 map of ‘Pomona or Mainland Orkney’ showing Kirkwall and the Peedie Sea. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Archaeological evidence points to the fact that the Hubbert has been used as a safe place to bring vessels into Egilsay, and the same kind of activity has been noted at the Oyce of Huip where a ‘lobster fisherman did anchor his small boat in there for a few months about fifty years ago but this was a matter of convenience as he lived nearby’ (personal communication from Ian Copper, Stronsay).

What then of the other place-names that appear to have this element? The most well-known is St Margaret’s Hope, South Ronaldsay. The earliest spelling we have for this name is ‘S. Margeret Houp’ from Blaeu’s 1654 map. Later, in 1700, James Wallace wrote that ‘St. Margaret’s Hope’ was ‘a very safe harbour for ships, which has no difficulty in coming to it’ (Wallace, p. 8), and MacKenzie’s map of 1750 also gives this modern spelling. Ronsvoe is an earlier name for the district around what became St Margaret’s Bay and seems to have been the precursor to that name. For this we do have earlier spellings including Ronaldiswaw (1492) Ronaldiswo (1500), Ronaldisvo (1595) all pre-dating the name ‘St Margaret’s Hope’ (Marwick, p. 173). That a person called Rǫngvaldr is associated with this large natural harbour and the island name itself is surely not coincidental. The area is still known by older locals as ‘Ronsa’ (Lamb, Place-names of South Ronaldsay and Burray, p. 144), and it seems likely that the Rǫgnvaldsvágr mentioned in Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar in the context of the eponymous king’s expedition to Scotland in the 1260s is the same place. It seems, then, that ‘St Margaret’s Hope’ is a later name replacing the earlier name associated with Rongvaldr. Lamb observes that this is ‘another instance of the saga vágr being replaced by hóp (Lamb, Testimony of the Orkneyingar, pp. 49–50). We can see this later use of ‘hope’ at Kirk Hope in Walls which was Ásmundarvágr in the Orkneyinga saga (chs 12 and 15). These two examples show that the use of ‘hope’, a later interpretation of what was ON hóp, came into common use after the Norse period in Orkney.

In fact, it seems that there is a concentration of ‘hope’ names around the south of Orkney. Along with St Margaret’s Hope and Kirk Hope we also find Long Hope, Ore Hope (both Walls) and Pan Hope in the northeast of Flotta. We do not have early attestations for any of these places, their earliest documentary appearance being on Mackenzie’s map of 1750, each marked as a place of ‘safe anchorage’ and all are absent from Blaeu’s 1654 map. To these we can add Aith Hope beside South Walls. The indications are that the early forms of ON hóp were later supplemented by a secondary meaning of the word that came to mean ‘safe anchorage’, especially for shipping seeking shelter. It perhaps meant ‘a place a refuge’ from the seas rather than a port or harbour.

Places for further investigation

Another place in Orkney that may be derived from ON hóp (not hope) is Whupland in Sanday (Lamb, Testimony of the Orkneyingar , pp. 49–50), which is another name for Braes Wick. Pool just north of Braes Wick is said to be, according to local tradition, a ‘Viking harbour’ where there is also a protecting reef and what seems to be a wall enclosing the area (see Canmore). There appears to be evidence of this being worked including a possible batsto – a jetty or boat slip of Scandinavian type (Hunter, Bond & Smith, p. 12). These landscape features at Pool fit with what we have learnt so far but the place-name and location do not quite accord (Lamb, Naggles, p. 69). The Hole of Wheppet (Birsay) divides Lamb and Marwick in their interpretations. Marwick, is uncertain as to the meaning of the first element whilst Lamb proposes hóp which he suggests picks up a ‘w’ as in the case of Whupland (Sanday) discussed above (Marwick, Birsay, p. 4, and Lamb, Testimony, p. 50).

Toab (Tollop, 1439) in Tankerness off Deer Sound may derive from ON toll plus hóp to give toll-bay (Marwick, Farm Names, p. 86), and there is evidence of several boat nausts at Mill Sand near Toab Skerries which might be of interest. Lamb proposes another toll-hóp at Cantick (South Walls) as it ‘is earlier recorded as Cantop on Blaeu’s 1654 map. The former is Cann-tollr-vik the latter Cann-tollr- hóp’ (Lamb, Testimony, pp. 49–50). Marwick, however, suggests another interpretation with Gaelic ceann ‘head or headland’ (Marwick, Farm Names, p. 184).

Matthew Blake and Corinna Rayner.

Illustration for ‘The History of Olav Trygvason’, Snorre Sturlason, Kongesagaer, 1899, NG.K&H.B.05049 – National Museum of Art, Architecture & Design (Public Domain).

Further Reading

Cleasby, Richard and Gudbrand Vigfusson, An Icelandic-English Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1874).

Clouston, J. Storer, Records of the Earldom of Orkney, 1299-1614 (Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable for the Scottish history Society, 1914).

Jakobsen, Jakob, An Etymological Dictionary of the Norn Language in Shetland, (Lerwick: 1928).

Hunter, John with Julie M. Bond & Andrea N. Smith. Investigations in Sanday, Orkney. Volume 1: excavations at Pool, Sanday, a multi-period settlement from Neolithic to Late Norse times (Kirkwall: Orcadian in association with Historic Scotland, 2007).

Lamb, Gregor, Naggles o Piapittem: Place Names of Sanday (Byrgisey: 1992).

Lamb, Gregor, The Testimony of the Orkneyingar (Byrgisey: 1993).

Lamb, Gregor, The Place-names of South Ronaldsay and Burray (Kirkwall: Bellavista Publications, 2006).

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

Marwick, Hugh, The Place-Names of Birsay (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1970).

Pollard E., J. Gibson and M. Littlewood, ‘Interpreting medieval inter-tidal feature at Weelie’s Taing on Papa Westray, Orkney, NE Scotland’ Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 11 (2016), pp. 299–322.

Sigurðardóttir, Aldís et al, eds, Dictionary of Old Norse Prose (ONP) (Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 1989‒2021).

Wallace, James, An account of the Islands of Orkney by James Wallace … ; to which is added an essay concerning the Thule of the ancients (London: 1700).

Previous Post

The First Bird-Watcher on North RonaldsayNext Post

‘Cancelled, no room to write’!No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply