07/09/2024, by aezcr

Who were the Papar of Papay?

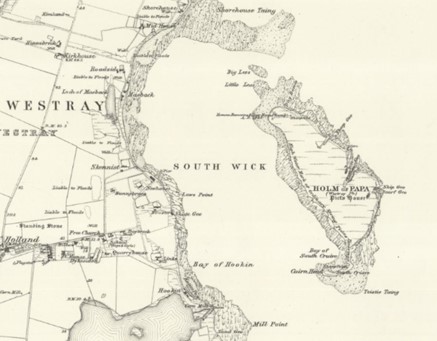

The place-name Papay (officially known as Papa Westray) derives from the ON term papi /papar meaning priest/priests and ON ey ‘island’ giving a meaning of ‘island of priests’. There are in fact several Papar names in Orkney, Papa Stronsay, the Steeven of Papy (North Ronaldsay), Papleyhouse (Eday), Papdale (Kirkwall, Mainland), Paplay (Holm) and Papley (South Ronaldsay). It is an intriguing name and it is not confined solely to Orkney with a further eight examples in Shetland and a total of twenty-eight throughout the northern and western isles of Scotland (See the Papar Project for more details). What then do we know of the papi that gave their name to Papay? There are several possibilities but here we will concentrate on what might be the earliest written reference to the island. We begin on the Holm (of Papay) which lies immediately to its east. It is a small uninhabited island populated only by ‘holmie’ sheep and the occasional visitor taken over as part of a guided tour. Just a short distance from Papay, the Holm shelters the Holm Sound and the bay of South Wick.

Detail from the 6” Ordnance Survey map (1882) showing the Holm of Papa. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Apart from the sheep, perhaps its most famous visitor, with an emphasis on perhaps was St. Findan (also known as Fintan, d.878), an Irish saint whose vita (Latin ‘life’) was written shortly after his death (Breen, pp. 502– 506). Whilst living in Ireland and prior to taking orders, sometime in the 840s, Findan was taken captive by Viking raiders (Nordmanni) and was sold several times. Later, on a ship on their way back, we presume to Norway, a sea battle erupted between rival Viking factions. The vita tells us that Findan ‘though held in chains, stood up, eager to bring help to his master and his companions’ (Omand, p. 285). As the conflict subsided Findan was rewarded by having his chains removed, and the journey continued east via Orkney ‘next to the land of the Picts’ (Omand, p. 286). Once in Orkney they ‘disembarked, recuperated, travelled here and there over the islands and waited for a fair wind’ and upon observing ‘their dissoluteness’, Findan ‘began to explore places on the islands and to worry about his safety and escape’ (Omand, p. 286). He fled successfully to an island which, as we will see later, is thought to be the Holm of Papay. Here, Findan, upon:

‘finding therefore a huge rock in a remote region, he set about hiding himself under it at once. The sea normally came up to this rock as the tide rose, so he did not know what to do or where to turn. On one side the sea pressed him; on the other side he was tormented by the fear of the enemy as they ran to and fro about him, walked on top of the rock under which he lay, and called for him by name from every quarter’ (Omand, p. 286).

The Holm of Papa, taken from Gowrie.

There are three chambered cairns on the Holm (in the south, north, and centre), and if the events did take place here, might one of these have been Findan’s hiding place? Although if the story can be taken literally, and perhaps it shouldn’t be, then it sounds as though his hiding place was perhaps more like a sea cave or a nook down some geo since,

‘preferring to endure the rage of the sea rather than fall into the hands of men passing all monsters in ferocity, he scorned the massive waves and remained in that place without food, that day and the following night (Omand, p. 286).

Once the Normanni had left he found that he was separated from a larger island by a stretch of water, and, after much anxiety about how he should cross this body of water,

‘though fully clothed, he jumped into the water. I’m about to tell you of marvellous things: divine compassion immediately made his clothes so stiff that, held up by them, he could not sink. His clothes seem to float and he was carried along to the land like this through the waves, unharmed’ (Omand, p. 287).

Findan roamed the island after what his chronicler, with possibly a bit of poetic license, describes as three days of wandering on the larger island (Papay). This probably references Jesus’ wanderings in the wilderness and may be a way for his biographer to indicate that Findan was destined for holiness. Eventually he found help and was led to the bishop of the region whom, we learn, had been educated in Ireland and spoke Irish. Findan stayed with the bishop for two years before heading to the continent, taking holy orders, and then carrying out missionary work.

St. Boniface, Papay. Image courtesy and Copyright of Jonathan Ford.

Did this take place on Papay and what are the implications if it did? Well, the evidence is slight but it has been argued by William Thomson that the descriptions of the places in which the events took place help us to locate them. Firstly, we have a small island adjacent to a larger one inhabited by a religious community and this fits with Papay and the Holm (Thomson, pp. 279–283). The relationship between Stronsay and Papa Stronsay, for example, would not work here since the Papa island is the smaller of the two. If there was an Irish speaking bishop on the island he might have been at St. Boniface’s, and here two carved stones have been found that can be dated to the seventh – ninth centuries, suggesting it was active in the time of, or up to, that of Findan. If the Holm and Papay were the two islands of the Findan story, and the evidence is suggestive rather than compelling, then it would make Papay home to a Pictish bishop in the mid-ninth century living alongside, or with the knowledge and arguably tacit acceptance, of Viking travellers in the islands, and so it may be during this period that the island was given its name and that the Papi of Papay were based at the church of St. Boniface.

Matthew Blake and Corinna Rayner.

Further Reading

The Papar Project website.

Breen, Aidan, ‘Fintan’, Dictionary of Irish Biography (2009).

Holder-Egger, Oswald ‘Life of St. Findan, Confessor’ (Vita Sancti Findani Confessoris), Monumenta Germaniae Historica Scriptores, 15 (Hanover: 1887, reprinted 1992), pp. 502¬506. For and online version see O’ Nolan, Kevin, (Trans.), ‘Life of St Findan’.

Omand, Christine J., (Trans.), ‘Life of Saint Findan’, in R. J. Berry and H. N. Firth, Aspects of Orkney: The People of Orkney (Orkney: The Orkney Press, 1986), pp. 284–287

Rendall, Jocelyn, ‘St. Boniface and the mission to the Northern Isles: a view from Papa Westray’, in Barbara E. Crawford (Ed.) The Papar in the North Atlantic: Environment and History (St. Andrews: University of St. Andres, 2002), pp. 31–37.

Thomson, William P. L., ‘St. Findan and the Pictish-Norse Transition’, in R. J. Berry and H. N. Firth, Aspects of Orkney: The People of Orkney (Orkney: The Orkney Press, 1986), pp. 279–283.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply