24/08/2024, by aezcr

Who is Ragna, What is She?

Readers of this blog might be wondering why our project is named after Ragna, a slightly obscure woman, and what her islands were. In fact, while the female characters of the Saga of the Earls of Orkney play a much more low-key role than the many warlike, poetical, ambiguous, saintly or evil male characters, the women are nevertheless pretty memorable in their own ways. One such female character, who makes only a couple of appearances, is Ragna. She gets a total of ten mentions in the saga, in three different chapters. But we can perhaps discern her importance from the fact that her son Þorsteinn is identified as such, i.e. as Rǫgnuson, rather than being given the much more common patronymic incorporating his father’s name.

Other than her son, we know nothing about Ragna’s family. No parents or other offspring are mentioned, and the use of the metronymic for her son suggests that she did not have a husband, at least at the times when she figures in the saga. Normally, even if a child’s father was dead, he would still be remembered in that child’s patronymic, so the use of a metronymic would arise only from special circumstances. One suggestion is that metronymics were used when the father died before the baby was born, as he had not had an opportunity to acknowledge the child. But it’s also possible that Ragna was just a widow, or a single mother, or possibly more important, or of higher social status, than her husband or father of her child. Unfortunately, we do not know what the special circumstances were in Ragna’s case.

That she was important is clearly indicated in the saga. In chapter 56, she is said to have been a ‘noble mistress of the household’, which is a rather clunky translation attempting to catch all the nuances of the Old Norse gǫfug húsfreyja. In chapter 67, she is said to have been an ‘intelligent woman’, vitr kona. One manuscript adds that she was ‘splendid’. Although we get no more authorial judgements than these, Ragna’s personal qualities shine through in the two saga episodes in which she firmly challenges two of the earls of Orkney.

In the twelfth century, Earl Páll Hákonarson became sole earl of Orkney after a curious incident at Orphir (ch. 55) in which the saga maintains that his half-brother and co-earl Haraldr was killed by putting on a sumptuous white linen garment embellished with gold, made by his mother Helga and aunt Frakǫkk (the latter another memorable female character in the saga). We do not know in what way the shirt had been made so deadly (poison? magic?), but the seamstresses had obviously intended it for Páll, so that his death would make way for his (probably illegitimate) half-brother Haraldr to inherit the whole of the earldom. Unfortunately, Haraldr was too covetous of the apparently gorgeous garment to listen to their entreaties for him not to put it on, and as soon as he did, that was the end of him.

Páll turns out not to be a particularly competent earl, and in chapter 67 he faces a challenge from Rǫgnvaldr Kali Kolsson, the Norwegian-born nephew of St Magnús Erlendsson, intent on claiming his share of the earldom. On his travels, Páll comes to stay with Ragna and she gives him some well-meant advice, as one would expect of an intelligent woman. The advice is in fact rather detailed:

‘It would be my advice in this difficulty facing you that you befriend as many as possible and don’t be quarrelsome. I would like you not to accuse Bishop Vilhjálmr or other kinsmen of Sveinn Ásleifarson, rather I wish that you give up your anger against the bishop, and moreover that you have a message sent to the Hebrides after Sveinn and give up your anger and him his properties, so that he can be to you like his father was. It has long been the practice of the noblest men to do a lot for their friends and garner themselves support and popularity.’

Páll will not have it, and presents an early example of mansplaining, as he rather petulantly tells Ragna:

‘You are a wise woman, Ragna, but you have not been allotted the title of earl in the Orkneys; you will not be in charge of governing here. It’s unbelievable that I should give Sveinn money for a settlement and think that that would give me a victory.’

Later on, he may well have wished he had followed Ragna’s advice, since it is this very Sveinn Ásleifarson that he dismisses here who turns out to be his nemesis, arranging for Páll’s kidnapping and removal from the scene so that Rǫgnvaldr can become sole earl (chs 73-4).

Shetland pony, a breed with a long, thick tail and dense winter coat to withstand harsh island weather. Reproduced courtesy of Pearson Scott Foresman (public domain).

Ragna seems to have been impartial in the endless feuds between the earls and she had no compunctions about challenging Rǫgnvaldr, either, though in rather a different context. In chapter 81, she and her son are visited by a wandering Icelandic poet, Hallr Þórarinsson. He is miffed because Rǫgnvaldr, a poet himself and patron of poets, has not welcomed Hallr at his court. It so happens that Ragna is on her way to see Rǫgnvaldr ‘on business’. If only we knew what business this noble lady had to transact with the earl! At any rate, she takes the opportunity to plead Hallr’s cause. Like many powerful women, she uses her appearance to make an impact: ‘She was dressed in such a way that she had a red headdress made of horsehair on her head.’

We may find it hard to imagine what kind of headdress she was wearing, though the headdresses worn by Icelandic women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries may give some clue. The headdress is a sign of a married woman, as unmarried women wore their hair loose. In the sagas red clothing is a sign of wealth and status, so Ragna is asserting her social position. Certainly the sight of her is startling enough to spur Rǫgnvaldr into spouting one of his more obscure verses. This verse is so interesting that I must save it for another occasion, and let us stick with Ragna for the moment. Suffice to say that he accuses her of having tied a mare’s tail around her neck. Ragna is not impressed with his powers of observation and retorts:

‘It has now come to this, as is said, that few are so intelligent that they can see everything as it is, because this is from a stallion and not a mare.’ She then took a silk cloth and wrapped it around her head and said no more about her case.

Ragna displays her intelligence in several ways. She first appeals to the authority of proverbial knowledge (‘as is said’), then disparages his intelligence, using the same adjective, vitr, that the saga narrator used of her. She then plays the gender card very successfully. In the sagas, mares are generally associated with unbridled female sexuality, so Rǫgnvaldr’s reference to a ‘mare’s tail’ is clearly intended as an insult. But Ragna has the last laugh, as her headdress is made from the hair of a stallion and she is thus more of a man than Rǫgnvaldr is. We can imagine her brandishing the stallion-hair headdress at Rǫgnvaldr. But the intelligent also know to stop when they have made their point, so she meekly covers her head in silk (indicating high-status femininity) and says no more. Eventually, Rǫgnvaldr warms to her and Hallr gets his wish, so that he and Rǫgnvaldr spend many happy hours together, composing an obscure and rather tedious poem called Háttalykill inn forni (‘The Ancient Key of Metres’). Result.

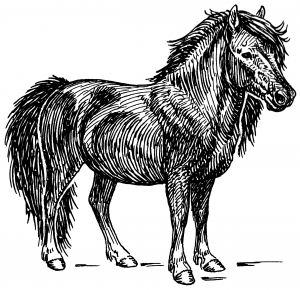

Detail from Blaeu’s 1654 map of Orkney showing the islands of North Ronaldsay and Papa Westray. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

So what exactly are Ragna’s islands? Well, the saga states that she and her son lived in North Ronaldsay (chs 56, 67 and 81) but that they also had another estate in Papa Westray (ch. 67). The saga calls this estate a bú, a word which usually indicates a large, multi-function landholding and not just any little farm. So Ragna is clearly associated with these two most northerly of Orkney’s North Isles and was likely the most prominent landholder on them.

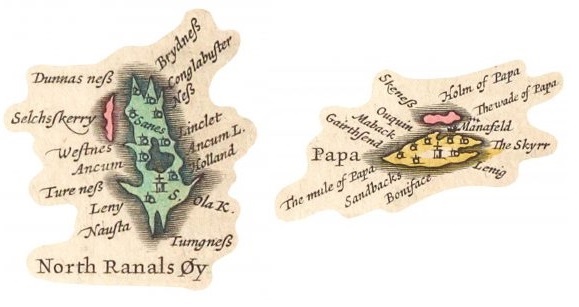

Detail from the 1834 Baldwin Cradock map of Scotland showing Fair Isle. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

The Fair Isle connection, however, is in truth rather tenuous. Ragna’s son Þorsteinn, who, the saga says, was ‘an excellent person’, gets involved in the events surrounding the arrival of Rǫgnvaldr in the isles to claim his inheritance. Rǫgnvaldr’s father, Kolr, tests the waters by sneakily approaching Shetland in such a way that the inhabitants of Fair Isle kindle a beacon to pass a message of the approaching enemy to places further south. In North Ronaldsay, Þorsteinn dutifully kindles his beacon once he sees the one burning in Fair Isle. When Rǫgnvaldr does not appear in Orkney, this causes dissension among the followers of Páll who had gathered to resist him, with everyone blaming Þorsteinn for having been too eager to light the North Ronaldsay beacon. Þorsteinn in his turn blames Dagfinnr from Fair Isle for the debacle, and even kills him with a well-aimed axe-blow.

View from the beacon site in Fair Isle. © Judith Jesch.

There appear to be no consequences from this act for Þorsteinn. He is even brought in by the bishop to help reconcile the feuding earls Páll and Rǫgnvaldr, suggesting his political importance and perhaps neutrality, like his mother. We don’t know if Þorsteinn had any further connection with Fair Isle, though I can’t help wondering if both the demise of Dagfinnr and the arrival of Rǫgnvaldr gave him an opportunity to acquire another estate there. Certainly, in the beacon episode, and probably for much of its history, Fair Isle had a rather ambiguous status between Orkney and Shetland. Could it be that Þorsteinn annexed it, at least temporarily, for Orkney? While that is pure speculation, it is clear that Þorsteinn was wily like his mother, a survivor in the rocky politics of the twelfth-century earldom.

Shakespeare’s answer to the question ‘Who is Silvia, what is she?’ was ‘Holy, fair, and wise is she; / The heaven such grace did lend her, / That she might admirèd be.’ Ragna was not as saccharine as the fair Silvia, but there can be no doubt that the saga compiler admired her.

Judith Jesch.

Further reading

Richard Perkins 1986-89, ‘Þrymskviða, st. 20, and a passage from Víglundar saga’, Saga-Book 22:279–84. [discusses headdresses]

Previous Post

Swona: A pig of a name?Next Post

Who were the Papar of Papay?No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply