13/08/2024, by aezcr

Swona: A pig of a name?

Swona lies in the Pentland Firth to the east of South Ronaldsay. It is unusual in that, for some reason, it does not feature in Marwick’s Orkney Farm Names. Understood to mean ‘Sveinn’s island’ by those that lived there, there is a rock called Grimsalie where Grimr of saga fame met the eponymous Sveinn (William Annal, Swona Heritage, personal communication). Swona occurs three times in the Saga of the Earls of Orkney in which we learn that Grímr lived there with his two sons Ásbjǫrn and Margaðr, both ‘very gallant men’ (chapters 56 and 66). In the AM 325 I 4° manuscript (ca. 1290–1310) the name is rendered Sviney, and in Flateyjarbók (1387-1394) as Svefney. A mid-fifteenth-century Scottish manuscript refers to a Swynay minor which is likely to be Swona although the minor affix is difficult to explain, it may possibly be in reference to Stroma which is the larger of the two islands that sit in the Pentland Firth (John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum).

Swona (courtesy of William Annal, Swona Heritage).

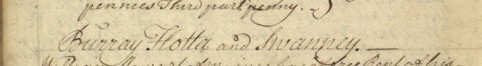

Our next references come in 1550 when we get a Swinnay spelling (Clouston, p. 243) and in 1556 when we see Swonay, the first spelling with an ‘o’ (Clouston, p. 285). Both these spellings, however, are from transcripts rather than original documents. Jo Ben, in the second half of the sixteenth century, gave a another ‘o’ spelling, this time Sownay, which he describes as ‘an island affording reliable mooring for foreign ships and fishing-boats. Oats and barley grow here, but the ground is quite sandy’ (Hunter, p. 44). Next, chronologically, is a 1614 testament dative (a document detailing someone’s estate if they die intestate), where the spelling is Swinnay (CC17/2/2), then, an undated but early seventeenth-century document provides Sowna, followed by Swanney in the 1653 Land Tax. This last spelling mirrors modern Swanney, Birsay on Mainland Orkney, which appears in a 1574 surname as Svinnay. Later forms include Souna (Blaeu, 1654), Swana (Adair, 1682), Swinna (Wallace, 1700), Swona (Mackenzie,1750), Swina (Dorret, 1751) and finally Swinna in Rev. Watson’s 1795 statistical account which gives a slightly different picture of the island to that presented by Jo Ben, describing it as ‘a barren inhospitable island, exposed on all sides to the utmost rage of the Pentland Firth’.

What then are the options for the first element? As discussed above Swona has been understood by those that lived there as ‘Sveinn’s Island’, however with a personal name we would expect the first element to be in the genitive singular, and the early saga spellings do not bear this out. Thus there does not seem to be any real evidence for the island being coined from the personal-name Sveinn. Marwick interprets the Birsay Swanney name as deriving from ON svín ‘pig’, and tentatively suggests that it may have derived from svina-dalr a ‘swine valley’ with the final element dalr being dropped at some point (Marwick, Farm Names, p. 138). There are a series of other island names around Scapa Flow that derive from animal names. We have, for example, Cava ‘calf’ which is probably instructive of its size, it being smaller than its neighbours, and Lamb Holm, seemingly self-evident, and Faray, ‘sheep island’, both indicate sheep husbandry. In the same vein, could Swona signal animal husbandry in a similar way to Lamb Holm and Faray? Svinøy ‘Swine Island’ is a common island name in Norway and also occurs in Landnámabók, suggesting that these may have been places for farming pigs.

In general pigs are not thought to thrive in windy, treeless places, however, in Orkney and Shetland a variety of hardy pig, the grice was the dominant pig of the Northern Isles through until the nineteenth century. It was a ‘small swine peculiar to the country… which are of a dunnish-white, brown or black colour with a nose remarkably strong, sharp pointed ears and back greatly arched, from which long, stiff bristles stand erect’ (Hibbert, pp. 426–427). According to this account the swine ‘roam abroad’ and were known to eat young lambs. In Tom Tulloch’s oral history account from 1970 he recalls the grice in Shetland and that, in his father’s time, it was common practice for the pigs to be in the hills and brought back to the farm for fattening up and slaughter. And there is earlier evidence. Blaeu, in his 1654 description of Orkney, commented that ‘there are also very many herds of pigs, grazing more cleanly than in Britain on the meadows, mountains and moors’. These pigs were an important part of local farming practices and the efficient foraging of the pig led, in some cases, to soil erosion and loss of farmland (Thomson, p. 146). We have evidence from the seventeenth century that pigs lived beyond the hill dyke of the toonship, a testimony to their hardiness and how they were farmed (Thomson, p. 163). It is notable that the ON element grice also makes its way into Orkney place-names. Grice Ness (Stronsay) from ON gríss ‘young pig, piglet’ plus ON nes ‘headland, promontory’ and Gricey Water on the westside of the island, for which Marwick suggests ‘pig-loch’.

A survey of pig bones across the Western and Northern Isles show that in the Western Isles pigs ate a mixed diet of ‘terrestrial and aquatic protein, with a predominantly herbivorous diet’ whilst at Orphir (Orkney Mainland) there was no evidence of marine protein. The sample is small, just one Orkney site, but nonetheless the authors conclude that the evidence ‘suggests a more formalised management’ of pigs at Orphir with two phases from the late 800s to the mid-1100s (Jones & Mulville, pp. 338–351). The indications are, however slight, that it was common practice across several centuries for pigs in the Northern Isles to be kept on rougher land. One might see from this that an enclosed or separate area for pigs, or an area that was known to be a place where pigs were beyond the toonship boundaries, might take on the name of a useful if occasionally disruptive beast.

Returning to the place-name element itself, we can see that the ‘i’ spellings remained fairly persistent which indicates an ON svín ‘pig’ origin. Just across the Pentland Firth in Caithness we have Lochend, formerly known as Swinnie Loch (Swynne, 1538), and ‘a name which probably derives from the very common ON appellative Svin-ey; swine island, with reference to an island in the loch’ (Waugh, pp. 255–256.). This mirrors a mid-fifteenth-century Swynay spelling for Sweyn Holm, off the north end of Gairsay. The occurrence of this island name and others suggests that this variety of Northern Isles pig, the grice, may have been contained within specific areas, Grice Ness perhaps suggests pasture land on which pigs could be securely maintained, since it is surround by water on three sides, and Gricey Water seems to differ, in that it is just a small loch, from Swinnie Loch (Caithness) which had an island called Swiney in it (Marwick, ‘Stronsay’, p. 77).

There are a number of other names across Orkney that might imply pig husbandry as well as Swannay (Birsay) as discussed above. Swandale (Swindale, 1595) in Rousay is also likely to incorporate a swine name, ON svín-dalr ‘swine-valley’ (Marwick, Farm Names, p. 65), and Sweenalay in Rendall may be ON svín ‘pig’ plus ON hlið ‘gate’ (Marwick, Farm Names, p. 65, and Sandnes, p. 151). Other place-names that may indicate the management of pigs include Trundigar and Troondie both in the hills between Firth and Harray for which Sandnes suggests ON þróndr ‘pig’, on account of Norwegian hill-names containing Tron- and since Trundigar may have been a term for a ‘pigsty’ (Sandnes, p. 153). These examples perhaps reveal other aspects of pig-management in the form of the gates through which pigs were released and brought back in from the hills, and to pigsties.

Pig, North Ronaldsay (2024).

In summary, the spellings do not allow for the personal-name Sveinn in Swona, and that understanding seems to be based on folk etymology, as with the rock there called Grinsalie. Additionally, there is abundant evidence in the range of names across Orkney that indicate the presence and husbandry of pigs. The semi-feral grice was an important part of the Orkney economy that required management in suitable places, and the island of Swona, where wild cattle now roam, appears to have been such a place.

Matthew Blake and Corinna Rayner

Further Reading

Clouston, J. Storer (ed.), Records of the Earldom of Orkney 1299-1614 edited by (Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable for the Scottish history Society, 1914).

Hibbert, Samuel, A description of the Shetland Islands: comprising an account of their geology, scenery, antiquities and superstitions, 1822 (Lerwick: 1891, reprint 1931).

Hunter, Margaret, ‘Jo: Ben’s Description of Orkney’, New Orkney Antiquarian Journal, 6 (Kirkwall, 2012), pp. 34–47.

Jones, Jennifer R. & Jacqui A. Mulville, ‘Norse Animal Husbandry in Liminal Environments: Stable Isotope Evidence from the Scottish North Atlantic Islands’, Environmental Archaeology, 23:4 (2018), pp. 338–351.

Marwick, Hugh, ‘Antiquarian notes on Stronsay’, Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society), V (1926-27), pp. 61–84.

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

Peterkin, A. (ed.), Rentals of the Ancient Earldom and Bishoprick of Orkney 1502–3 and 1595 (Edinburgh: J. Moir, 1820).

Sandnes, Berit, From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney (Scottish Place-Name Society, 2010).

Thomson, William, Orkney Land and People (The Orcadian Limited, Kirkwall Press, 2008).

Wallace, James, An account of the Islands of Orkney by James Wallace … ; to which is added an essay concerning the Thule of the ancients (London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, 1700).

Watson, Rev. Mr James, ‘The Statistical Accounts of Scotland, Orkney (Ronaldshay and Burray, County of Orkney’, OSA, XV, (1795).

Waugh, Doreen, The Place-names of Six Parishes of Caithness, Unpublished PhD (University of Edinburgh, 1985).

Historical Tax Rolls, Land tax rolls for Orkney, volume 01, E106/24/1/59, National Records of Scotland.

John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, MS O. 9. 9., Cambridge, Trinity College.

Orkney and Shetland Commissary Court, CC17/2/2, National Records of Scotland.

Previous Post

Sword-storm off Rauðabjǫrg?Next Post

Who is Ragna, What is She?No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply