03/08/2024, by aezcr

Sword-storm off Rauðabjǫrg?

Rauðabjǫrg is the location of the great sea battle between Earl Þorfinnr and Earl Rǫgnvaldr in the Saga of the Earls of Orkney in which we hear that:

‘Earl Rǫgnvaldr gathered his army in the Orkneys and intended to go over to Ness, and when he arrived at the Pentland Firth then he had thirty large ships. Earl Þorfinnr came to meet him and had sixty ships, mostly small. Their meeting took place off Roeberry, and they went straight into battle.’

We are told in a verse quoted in the saga that in this battle ‘our beloved friends nearly destroyed each other, when the sword-storm then happened off Rauðabjǫrg’ (chapters 26 and 32). That the name occurs in a verse section of the saga is helpful because these sections are generally thought to be earlier in date and as this poem can be fairly confidently dated to the eleventh century so is important evidence for the place-name (Whaley, pp. 253–254).

Detail from a woodcut illustration from the 1899 Norwegian translation of Heimskringla. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design (public domain).

Several locations have been suggested for the site of Rauðabjǫrg, but its exact whereabouts remains uncertain. The name seems to derive from ON bjarg ‘hill, cliff, crag’ which, in the plural (as here), often refers to coastal cliffs (ONP) and ON rauðr ‘red, reddish, blood red’ (ONP), giving ‘red cliffs’.

Nordal, back in 1916, proposed Dunnet Head in Caithness as the location. Dunnet Head is a large steep-sided promontory of red sandstone, so both a recognisable and visible headland. Historically we know of two names that have been used for that promontory. The first is Quinicnap Head (1595), Whindiknop Head (1662), Windy Knap (1750) suggesting an origin of either ON vindr ‘wind, windy’ (ONP) or Scots wind with ON knappr ‘knob, ball’ (ONP), giving ‘windy knob’. The other name still in use today is Dunnet: Donotf (1223-24), Dimosc (1275), Dunost (1276), Dunneth (1455), Donet (1539). This name is likely to apply to the whole promontory as well as the modern settlement, and is a name that Waugh proposes was ‘in use before the advent of either Norse or Gaelic-speaking people’ and so the meaning is not clear cut, but could derive from a sense of a hill/fort (Waugh, pp. 246 –247). For Dunnet Head, then, we are fortunate to have two names with good and relatively early provenance, neither of which indicate that colour was a significant identifier. As such, it is difficult to have confidence in assigning Rauðabjǫrg to Dunnet Head. Taylor discussed the plausibility of Rattar Brough just to the east of Dunnet Head but dismisses it for a variety of reasons, and Waugh does not support any interpretation of Rattar being a corruption of ON rauða (Taylor, p. 43, and Waugh p. 257).

Another suggestion is that Rauðabjǫrg is Roeberry in South Ronaldsay (Jesch, pp. 78, 207). The place-name elements match well with the name found in the saga, and it is one of the largest farms on the island facing southwards across Widewall Bay and out towards the Pentland Firth. While this is a plausible suggestion, the fact that the name does not appear in any of the early rentals is disappointing, and it is not until 1750 that it appears as ‘Roeber’ (Marwick, p. 177). It is possible, however, that the farm came much later and topographical names are not found in the surviving Orkney records in any great number, due to the nature of the surviving records, and so this remains a plausible site. There is, however, a suspicion that this is an imported name since, ‘the origin is fairly clearly ON rauða-berg, red rock or headland, but such a name is usually applied to a bolder headland than can be seen here’ (Marwick, p. 177). It may, however, be that instead of using the word ‘headland’, ‘cliff’ or ‘cliff-face’ may be more appropriate, certainly the ONP does not give headland as a meaning for berg. While the shore frontage does have a strong reddish colour facing the water, and despite being on a slight rise, it is not really berg-like, although in Orkney slight inclines can be more prominent than we might expect, see many of the Holland names found across the islands.

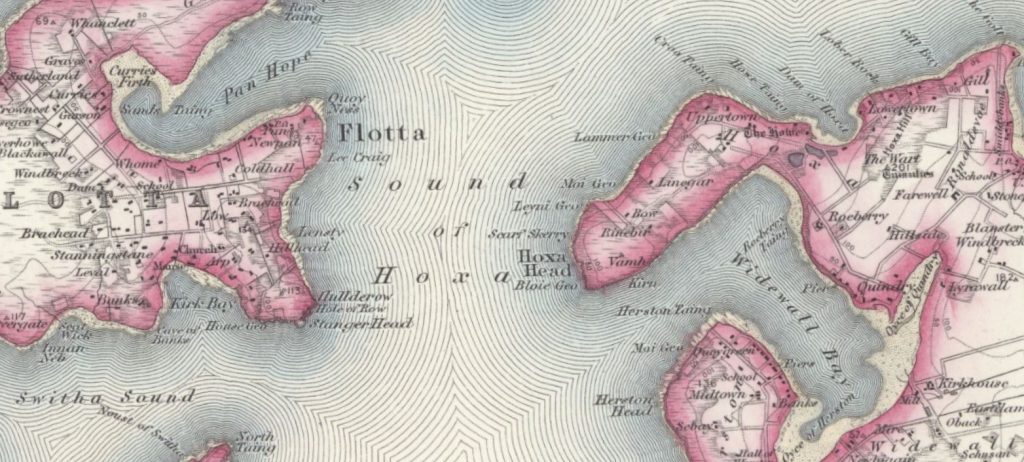

Detail from the first edition 1 inch Ordnance Survey (OS) map. Sheet 117 showing the location of Roeberry off Widewall Bay, 1886. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

If we return to the saga, we are reminded that ‘Earl Rǫgnvaldr arrived at the Pentland Firth’ where ‘Earl Þorfinnr came to meet him’ and that ‘their meeting took place off Roeberry’ (chapter 26). If the battle took place off Roeberry in South Ronaldsay it would mean that the battle took place in the enclosed waters of Widewall Bay. This cannot really be said to be in the Pentland Firth. Furthermore, Widewall Bay was a place-name known and used in the saga (Víðivágr): ‘they sailed thirteen ships west into the Pentland Firth and made for South Ronaldsay and landed in Widewall Bay and went ashore there’ (chapter 94). It would seem unlikely then that if the battle did take place in Widewall Bay that it would not be named in this passage. None of this means we can conclusively rule out the possibility of Roeberry being the Rauðabjǫrg of the saga but there is scope for doubt.

Another location that might be deemed suitable is to be found on the western side of Stroma where there is a headland called Red Head. Stroma is on the current Gills Bay to St Margaret’s Hope ferry route and is the shortest way between Caithness and Orkney.

Detail from MacKenzie’s map of the South Isles of Orkney (1750), showing the location of Stroma Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

While we do not have any early forms for it the meaning of the name is transparent and describes the promontory of red sandstone that is there (Waugh, p. 336). Stroma is considered part of Caithness but its ownership was contested during the medieval period. The saga tells us that after leaving Stroma ‘Sveinn went over to Caithness and Earl Haraldr over to the Orkneys’ suggesting a place that what not quite one or the other. That Sveinn Ásleifarson was chased there by Earl Haraldr suggests it was a place perhaps that was a little edgy (chapter 97), just beyond and not quite Caithness, not quite Orkney, in the midst of the turbulent Pentland Firth. Taylor dismisses the location precisely because of the rough waters arguing that ‘it is unlikely that either would seek battle so near to the famous Swelchie’ (Taylor, p. 44). On Murdo Mackenzie’s 1750 map an eddy is marked to the west of the island of Red Head ‘within which there is little or no stream’, perhaps a good place for a number of boats to lay up, if conditions were right. All in all, though, the evidence for Red Head on Stroma is circumstantial and not entirely compelling.

The Pálsson and Edwards translation of the Orkneyinga saga proposes that it is Roberry in South Walls that is Rauðabjǫrg (chapters 26 and 32).

Detail from the 25 inch OS map (CXXIII.10 & 11) 1900, showing the location of Roeberry, South Walls. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Here the spellings are a little confused, the modern OS map gives Roeberry, as does the 1882 25 inch OS map, and the OS name book recording local spellings gives ‘Ruberry and Ru’ Berry (OS1/23/11/72). While the name fits, we once again have no early forms on account of it not being a farm name and the dearth of sources for topographical names. Nonetheless we can be fairly confident that it is not a, much later at least, addition to the landscape. Burial mounds and funerary sites from across the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age identify this spot as important with the mounds possibly having been visible from the sea. The importance of such mounds to navigation has been discussed by Sanmark and Mcleod (pp 11, 13) and at nearby Aith there may have been a portage across the narrow shore line which shows the area to have been actively used during the Norse period (McCullough, pp. 225-226). The case for the battle having taken place here rests very much on two things, that South Walls was on the route to Caithness that Rognvaldr took, and, that it is in the Pentland Firth. Our knowledge of routes across the Pentland Firth during that period is uncertain but as a route out of Scapa heading towards Caithness this seems plausible, given the right conditions. We hear elsewhere in the saga that Earl Haraldr sailed from Caithness to Walls (chapter 97) and elsewhere that:

‘Sveinn encouraged Earl Erlendr and his men to head their ships out to Walls and they were to lie there by the Firth where they could see the comings of ships as soon as they left the headland. It was thought to be a good place to launch an attack, if there was an opportunity’ (chapter 94).

This to some extent mirrors the later activity in chapter 97, it places Walls in the centre of maritime activity. To summarise, there is much to recommend the site at South Walls in terms of the portage site, the saga documenting it as a routeway between Orkney and Caithness and the fact that it has had a long history of cultural significance and visibility.

Matthew Blake and Corinna Rayner

Further Reading

Jesch, Judith, Ships and men in the late Viking Age: the vocabulary of runic inscriptions and skaldic verse (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001).

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

McCullough, David, Investigating portages in the Norse maritime landscape of Scotland and the isles. Unpublished PhD, (University of Glasgow, 2000).

Nordal, Sigurður, Orkneyinga saga (København : S. L. Møllers, 1916).

Pálsson, H, and P. Edwards (trans.), Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney, (London: Penguin, 1981).

Sanmark, A. and S. McLeod, ‘Norse Navigation in the Northern Isles’, Journal of the North Atlantic, 44 (2024), pp. 1–26.

Sigurðardóttir, Aldís et al. (eds), Dictionary of Old Norse Prose (ONP) (Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 1989‒2021).

Taylor, Alex B. ‘Some saga place-names’, Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society, 10 (1922-1928), pp. 41–45.

Waugh, Doreen, The Place-names of Six Parishes of Caithness, Unpublished PhD (University of Edinburgh: 1985).

For more on the poetry see Diana Whaley (ed.) ‘Arnórr jarlaskáld Þórðarson, Þorfinnsdrápa 20’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), ‘Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300’, Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages, 2 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009), pp. 253–254.

Previous Post

The skaill-sites of Viking and Late Norse OrkneyNext Post

Swona: A pig of a name?No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply