23/07/2024, by aezcr

The skaill-sites of Viking and Late Norse Orkney

The Orkneyinga saga follows the triumphs, tribulations and travels of the earls of Orkney. The earldom is frequently ruled by two or three earls – often brothers or cousins – usually sharing power uneasily. So the saga shimmers with tensions and rivalries. In this febrile atmosphere, many of the earls do not die in their beds. Earl Einar is murdered in a great hall at Hlaupandanes (chapter 16), Earl Paul is kidnapped during a stay in a hall at Westness on Rousay (ch. 74), others die in more conventional battles. The political world is complex and game-changing confrontations, often played out in halls, are key to brokering relationships and shoring up allegiances. This blog will look at these important meeting-places, the halls – ‘skaill’ from Old Norse skáli ‘hall’ – of the saga and the several identifiable skaill/hall-sites of Orkney, many of which can be visited or observed.

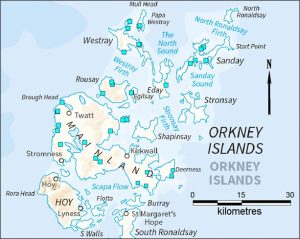

Map indicating with blue squares the locations of all Skaill place-names in Orkney. © Jane Harrison.

The earls – especially before the 1200s – ruled with the backing of a military-type retinue and the allegiance of leading landholders. Winning and maintaining the loyalty of key individuals was essential to success. In return for these people’s support, including a supply of fighting men, and of taxes and renders-in-kind (cattle, crops, cloth, ale and so on) the earls provided opportunity, preferment, gifts and protection. The relationships were very personal and often negotiated and confirmed at feasts and ceremonial meetings. The earls moved around their estates and the landholdings of influential figures to maintain this system, visiting and staying at a network of head farms and elite dwellings, where earl-level hospitality could be provided.

These farms were organised around the open-plan hall of a longhouse: a suitable venue for feasts and meetings. Within the hall, side benches lined the walls, a hearth or hearths were arranged on the floor and the walls were no doubt decorated, creating an environment both comfortable and impressive. As well as alcohol-fuelled feasts, the halls were places for oath-taking, gift- and law-giving, involving the earls and at a more local level. The hall or skáli may have had a workshop or byre attached, adding to its length and perhaps a cooking area extending the opposite end, as at Skaill, Snusgar in West Mainland.

Viking hall longhouse at Bay of Skaill, Orkney Mainland, looking west. © Jane Harrison.

Around it were spread paved yards, workshops, food preparation and metal-working areas, extra outbuildings and barns or byres, perhaps even another longhouse. Together these complexes were of sufficient stature and flexibility to accommodate everyone, stable the horses, store the renders, and host the ceremonial gatherings. Successful earls and leading figures were notable for their generosity and feast-giving. In chapter 20 of Orkneyinga saga, Earl Thorfinn makes a name for himself by lavishly feasting his men and others of great reputation throughout the winter, not just at a Christmas feast.

These drinking and feasting halls are often referred to in the saga as skáli, including Thorkell’s hall in Deerness (ch.16); Sven Asleifsson’s drinking hall on Gairsay (e.g. ch. 105); and Earl Erlend’s on Damsay (e.g. ch. 94). The 38 surviving skáli-sites on Orkney are well-distributed across the islands. These head farms and local centres, where renders and taxes from the surrounding area were collected, were not the chief earl-bases at the pinnacle, these were Birsay and Earl’s Bu Orphir, later Kirkwall, but an essential and highly significant network supporting the operation of local and earldom economic, political and social culture.

Bay of Skaill, Mainland looking NW with the longhouse excavations foreground. © Oxford University.

The farms on Papay and North Ronaldsay belonging to Ragna and her estimable son, Thorstein (ch. 56), would have belonged to this category.

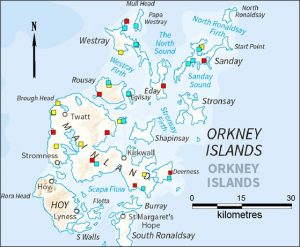

Map showing the locations of Skaill (red squares), Langskaill (blue squares) and ‘other’ Skaill (yellow) place-names. © Jane Harrison.

The Orkney skaill-sites, variously named Skaill (10 sites), Langskaill (14), but also Netherskaill, Breckiskaill, Aikerskaill, Backaskaill and so on, share many characteristics. They are on productive land, with access to fresh water, and to common and grazing land; near the coast, often on bay arms and/or in strategic locations, with good sea and land communications or overlooking key sailing routes; built on significant mounds or eminences and visually dominant, especially from the sea. The dominant mound-top location seems to have been one of the main factors deciding location.

There has been an argument that new Viking settlers deliberately built their longhouses over Iron Age and Pictish houses as a blunt statement of taking over. This is not the case. Rather they chose the best site according to the factors listed above. Then, once the first Viking longhouse had been raised all its extensions, alterations and re-building happened in the same prominent location and incorporating earlier walls and elements. So the mound grew bigger and earlier Viking buildings were included and referenced, creating an architectural history of the inhabitants’ local dominance and significance. This way of building was recorded at excavations including those at Skaill (Bay of Skaill), Skaill (Deerness) and Langskaill (Westray).

Northskaill, Sanday on its mound. © Jane Harrison.

The hall-builders also made clever, careful and wide use of stored midden (rubbish) originating from the kitchen, field and byre. They exploited the rotted, sticky, organic material as wall-core and backing for stone walls, for landscaping mounds and sealing floors. An abundance of midden reflected their success in farming, fishing and hunting and the length of their residence. It also carried the stories of their lives. Particular moments, perhaps the death of a local leader, or a major change in the house, were marked by what archaeologists call ‘special deposits,’ similar to time capsules buried today – special collections of objects laid under flags and new walls. These collections included cat skeletons and quern stones, both linked to fertility, and large decorated bone combs, connected to personal identity. Combs similar to deposited ones are displayed in the Orkney Museum.

Papay has two hall/skaill-names: Breckiskaill and Backiskaill, the latter only 300m west of the former, ON brekka ‘slope’ and ON bakki ‘bank’. The modern farm of Backiskaill is on the coast where once was one of Papay’s best harbours, with a large settlement mound, King’s Craig, just to the south, which is eroding and revealing walling and midden layers. Backiskaill looks across to the large farm of Skaill on Westray, sitting on a sizeable mound. Between the two Papay skaill-sites are possible burnt mounds and disturbed ground. The two sites together probably mark the division of an original, larger skaill-site. Might Ragna, her son or her estate manager have lived here? It is entirely possible. The large farm at Holland – possibly meaning settlement on a hill-spur/raised ground – is another candidate.

There are no skaill-names on North Ronaldsay but on South Bay, the right side of the bay for sailing routes to Papay, are Howar, ON Haugar ‘mounds’, and another Holland. The bay contains settlement mounds, a possible broch and a wealth of enticing archaeological possibilities. Might Ragna’s North Ronaldsay estate have been centred on this bay?

Travelling around Orkney’s islands be aware of the skaill-sites and their locations and imagine the bustle of preparation for the visit of a travelling earl or leading figure and the drama of events that would unfold in the fire-lit, crowded and impressive halls at the centre of the sites.

as an additional bit of interest…Westness on North Ronaldsay is known in local folk history as a the site of a Viking drinking hall. Garso Bay would have provided a safe harbour