26/06/2024, by aezcr

Knarston: a man or a ship, a staðr or a stǫð?

Knarston occurs six times in the Saga of the Earls of Orkney and its earliest attestations are in the AM 325 I 4° manuscript (ca. 1290–1310). We hear in the saga that ‘Jaddvǫr, the daughter of Earl Erlendr, lived at Knarston with her son Borgarr’ (chapter 56), that later ‘Arnkell… lived there, along with his sons Hánefr and Sigurðr’ (chapter 66), and then that ‘Bótólfr Hindrance lived there… an Icelandic man and a good poet’ (chapter 94). Interestingly, in the 1615 Danish manuscript the place referred to in chapter 56 is Jadvarstodum rather than Knarrarstodum, with the place evidently taking on the name of Earl Erlendr’s daughter Jaddvǫr. Presumably this name was in an earlier manuscript that the Danish translation copied from, but we cannot check.

There are three Knarston place-names in Orkney, one in Rousay, one in Harray, and one in St. Ola. We can be confident that the saga Knarston refers to that in St. Ola since the text provides recognizable geographical context: ‘Grímr joined them on the ship and they took Sveinn [Ásleifarson] to Knarston (a Knarrarstaþi) in Scapa’ (chapter 66), and ‘the earls lay with fourteen ships at Scapa off Knarston’ (fyrir Knarrarstauþu) (chapter 94). The context provided by the saga suggests that Knarston was a place of some status since Jaddvǫr, referred to above, was the daughter of Earl Erlendr (and so half-sister of St. Magnus), and Earl Rǫgnvaldr attended a Christmas feast there. It is also clear from the saga that it was a good landing place for ships.

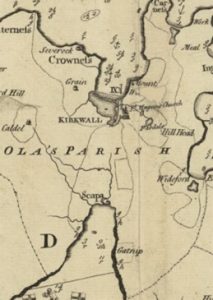

The precise location of Knarston is uncertain, it does not occur in the Ordnance Survey (OS) name books, but does appear on the 1961 OS map.

Detail from 1961 OS showing the location of Knarston and Lower Scapa. © Landmark Information Group Ltd and Crown copyright 2024. FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY.

There is an 1858 map of Orkney that places Knarston above the bay where there are low cliffs, rather than on the shore as the OS does. If, as the 1961 OS has it, it was located on the beachy shore of Scapa Bay at the mouth of a watercourse (visible on Mackenzie’s 1750 map) then its close proximity to Kirkwall across a narrow neck of land with this watercourse is striking.

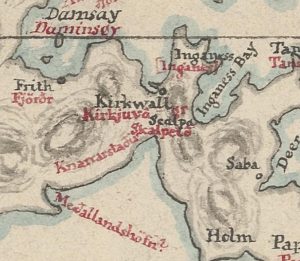

Detail from an unpublished map of Orkney by P. A. Munch, 80ga54723, 1858, National Library of Norway.

Detail from Mckenzie’s map of Orkney Mainland showing the area of Knarston, with a watercourse flowing from the direction of Kirkwall (1750). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Focusing on the second (generic) element initially, ON staðr, in the singular, is a noun with many applications. In place-names, it is generally interpreted as ‘farm-settlement/ dwelling’, but may also refer to a ‘bishop’s seat, bishop’s farm, monastery’, a ‘(fortified) city, town, palace or place where someone/ something belongs’, or a ‘place where someone/something stops and stays’ (ONP). A common place-name element in Orkney as well as Norway and Iceland, Nicolaisen counts some 2500 in Norway and around 1165 in Iceland (Crawford, p. 33).

Four –staðir (notably in the plural) names appear in the Saga of the Earls of Orkney, all of which arguably have personal names as their first (specific) element: Knarrarstauþum/Knarrarstaþi (Knarston), Kiarreksstauþum (Cairston), Jadvarstodum (Gaitnip?), and Skeggbiarnarstauþum (unlocated, possibly in Deerness). Marwick, who counts twenty-three Orkney –staðir names, states that this element in place-names is ‘always, or nearly always, combined with a personal name’ (Marwick, p. 235).

Orkney –staðir names, including Cairston and Knarston, largely developed the –ston ending that we see today, and most had acquired an intermediate –stane ending by the time of the 1595 rental (Crawford, pp. 33–34). Marwick observed that ‘staðir-names tend to be located in inland arable districts at a comparatively low altitude’. This tendency may indicate that the –staðir element signals ‘divisions of an older estate, granted out to individuals’ (Crawford, p. 31). The reason for the staðir-names occurring in the dative (but sometimes accusative) plural in the saga has received some discussion, and one suggestion is that the form ‘may well refer to a farm-group’ perhaps ‘under the supervision of one person’ (Waugh, p. 62). Knarston St. Ola, however, cannot be said to be inland, it is very much a coastal place, even if we locate it slightly inland on land at Lingro as Marwick suggests. This, and the context of the saga, perhaps provides a clue to an alternative interpretation, that the second element is ON stǫð ‘landing-place, a jetty’ rather than staðir. However, the Knarrarstauþum/Knarrarstaþi forms both occur in the earliest AM 325 I 4° manuscript, the second of which, is in the accusative plural, and can only come from staðr, since the accusative plural of stǫð would be stǫðvar.

Turning to the first element, Marwick interprets Knarston as Knǫrr’s staðir, with Knǫrr being a personal-name. He interprets the Rousay and Harray examples as such too, but for Harray suggests Narfastaðir ‘stead or settlement of Narfi, (Marwick, pp. 142-143). The saga indicates that the St. Ola Knarston saw different occupiers over a relatively short space of time, with Jaddvǫr and Borgarr, then Arnkell, Hánefr and Sigurðr, and then Bótólfr Hindrance. This gives a sense of the potential transient nature of these names, adding weight to Marwick’s premise that the first elements in –staðir names are almost always personal names. These names perhaps changed with the changing occupier.

Instead of a personal-name, Sandnes argues that the term knǫrr- refers to a type of ship, specifically a ‘large Nordic merchant and warship’ (ONP). ‘Ship-[landing] place’, then, is a possible interpretation here particularly given the context provided by the saga of ships landing there. But, the presence of the accusative plural form of staðr occurring in the earliest manuscript must cast some doubt over this. If, however, the accusative form is a scribal error, there is room for the notion that the name may refer to several boat stances, in line with Waugh’s thoughts on the ‘farm-group’ interpretation, since you may expect to lay up several boats (as is suggested by the saga) rather than just one.

Image showing several ‘nousts’ at Cott, Papa Westray, demonstrating that places where vessels were pulled up were not necessarily solitary, as indicated by the saga when ‘the earls lay with fourteen ships at Scapa off Knarston’.

If the number of stances can provide evidence of a place having more functions, then the possibility emerges of a strategic landing-place and potential portage between Knarston and Kirkwall (Crawford, p. 35).

Kirkwall from Knarston with the, now heavily drained, watercourse in the foreground.

The modern landscape has been thoroughly drained with holding pools and a larger drain called the Crantit Canal leading water out of the former wetlands. It is possible to envisage, at the very least, partial waterborne access from Knarston providing a shortcut to Kirkwall from the south and avoiding the dangers that an open sea journey would present. Indeed the nearby place-name Scapa perhaps strengthens this possibility, since ON Skalpr is ‘a poetic term for a ship’ (Marwick, p. 100), and ON eið ‘neck of land, isthmus’ (ONP), ‘seems to refer to isthmuses that were used as portages for goods or people and probably also stretches of land which served as portages’ (Sanmark and McLeod, p. 44).

The additional ship name together with eið may, then, lend further weight to –stǫð being the second element in Knarston. As well as indicating a place where warships were pulled up there is also the possibility, with knǫrr interpreted as a ‘trading ship’ (Jesch, pp. 129-130), that the place-name indicates a trading place, or at least a place to load and unload your cargo from and for Kirkwall, or perhaps to trade on the beach.

Image showing the low-lying ground between Knarston (left) and Kirkwall (right).

In summary then, it is difficult to be certain of both Knarston’s location and interpretation. If located above Scapa Bay near Lingro, and if the accusative plural form, Knarrarstaþi, is correct then ‘Knǫrr’s steads’ is the more plausible. If, however, it is located on the shore as the OS has it, and a scribal error can be argued for the accusative plural form, then, given the context provided by the saga, Knarston’s strategic position for access to Kirkwall and the Bay of Scapa, it can perhaps be interpreted as ‘the place with war/trading ship landing stances’. This interpretation together with the Scapa ‘ship-isthmus’ name, and the evidence of extensive drainage between Knarston and Kirkwall, make the area ripe for further investigation as a potential portage site and trading route or place.

Corinna Rayner and Matthew Blake.

Further Reading

Bates, Martin, Richard Bates, Barbara Crawford, and Alexandra Sanmark, ‘The Norse Waterways of West Mainland Orkney, Scotland’, Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 20 (1–2) 2020, pp.25–42.

Crawford, B. E. 2006, ‘Huseby, Harray and Knarston in the West Mainland of Orkney: Toponymic Indicators of Administrative Authority?’, in Names through the Looking-Glass, ed. by P. Gammeltoft and B. Jørgensen (Copenhagen: C. A. Reitzels Forlag A/S, 2006), pp. 21–44.

Horne, Tom, A Viking Market Kingdom in Ireland and Britain (Oxford: Routledge, 2022).

Jesch, Judith, Ships and men in the late Viking Age: the vocabulary of runic inscriptions and skaldic verse (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001).

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

Sandnes, Berit, From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney (Scottish Place-Name Society, 2010).

Sanmark, Alexandra and Shane Mcleod, ‘Norse Navigation in the Northern Isles’ JONA 13:44 (2024).

Thomson, William P. L., Orkney Land and People, (Kirkwall: Kirkwall Press, 2008).

Waugh, Doreen, ‘The Scandinavian Element Staðir in Caithness, Orkney and Shetland’, NOMINA (1987), pp. 62–74.

Previous Post

Woo… Hoo… Hooking and HookinNext Post

A Clerical ConundrumNo comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply