18/06/2024, by aezcr

Woo… Hoo… Hooking and Hookin

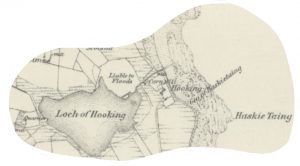

Detail from the 1882 Ordnance Survey map of North Ronaldsay showing Hooking and Hooking Loch. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Whilst walking in North Ronaldsay we were struck by the fact that the geographical setting of Hooking was markedly similar to Hookin in Papay.

The North Ronaldsay Hooking lies on the east coast of the island in Linklet Bay, on its landward side is the Loch of Hooking with a, now canalized, watercourse serving a corn mill before emptying into the bay.

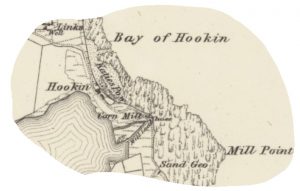

Hookin, Papa Westray likewise lies on the east coast of the island, on its landward side is St. Tredwell’s Loch with two nearby watercourses (one a man-made mill lade) emptying into the Bay of Hookin. The lade served a corn mill.

Detail from the 1882 OS map of Papa Westray showing Hookin and the Loch of St. Tredwell. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Marwick discusses both place-names several times, ‘a difficult name’, he vies between á(r)-kvern, ON á ‘river, burn’ with ON kvern ‘quern, millstone’ denoting a water mill rather than a hand-quern at North Ronaldsay, and, á(r)-kvin ‘the burn quoy’ á with ON kví ‘animal fold, enclosure’ (on account of the lack of a final n in 1618 and 1634 spellings, see below) plus the suffixed definite article at Papay (Marwick, 1924, p.43; 1952, pp. 5, 46).

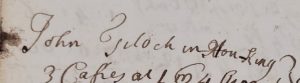

Hou-king in an ‘Accompt of what bear (bere) was left in the Island of Northronalshy’ 15th September 1721, Orkney Archives, D14/3/2.

Turning to the spellings, Marwick noted several for Papay (Howquyne 1601, Vquoy 1618, Howquoy 1634, Howkin 1636, Ouquin 1654, Uquinland 1654, Uqunland 1658, Ouking 1740) but just one comparatively late, Hooking 1798, attestation for North Ronaldsay for which he provides no reference. Thanks to our wonderful project volunteers, however, we have a few more attestations, four of which predate Marwick’s, including Hou-king 1721, Howkin 1723, Hakin 1723, and Hakin 1724.

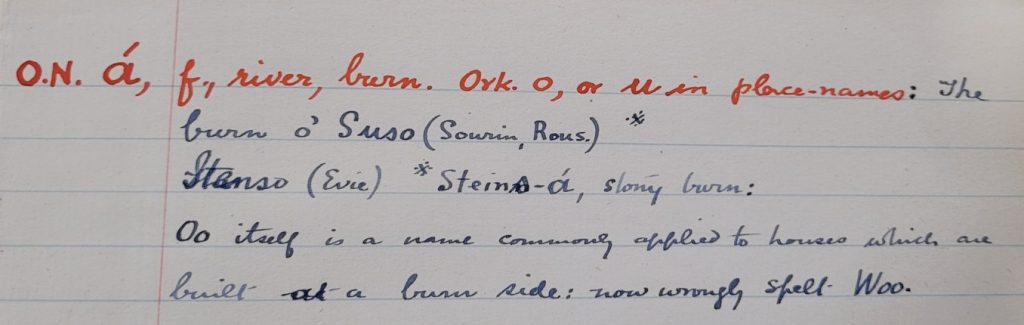

Entry for ON á in Marwick’s manuscript notes on Norn vocabulary and place-names, ca.1920, Orkney Archives, D29/9/19.

The development of the á to Hoo- is notable since other Orkney place-names thought to contain this element include Sands of Woo (Rapness, Westray), and Woo (Evie, Mainland). The Westray example has the earliest attestations, occurring in the 1492 rental as ‘Owe’, and ‘Ow’ in both the 1500 and 1595 rentals. It is in the 1841 census that it occurs as Wool, at some point losing the ‘l’ to become Woo (Huser, p. 81). The Evie example, a farm name taking on the name of a nearby burn, occurs in the 1624 saisines (court records) as ‘Ow’ (Sandnes, p. 157). In his manuscript notes on Norn vocabulary in place-names, Marwick remarks ‘Oo itself is a name commonly applied to houses which are built at a burn side: now wrongly spelt Woo.’

Detail from the 1882 Ordnance Survey map of Sanday showing Hookin Links (outlined) and The Knowes above. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

The ‘Hoo-’ spelling also occurs in a Sanday field-name, Hookin Links (outlined in blue) near Newark on the east coast of the island, where ‘it is applied as a name to links just north of Newark where a burn drains a marsh out into the sea. Here formerly stood an old water mill’. This location and situation, then, also supports an á(r)-kvern interpretation (Marwick, 1923, p. 63).

For this Sanday example, Gregor Lamb opts for an entirely different interpretation, ON hauga–kvín ‘mound-enclosure’ (Lamb, p. 35), and this is perhaps supported by the presence of The Knowes that are arguably in close proximity. However, since we have no early spellings for the Sanday example, the similarity of the situation of this place to those in Papay and North Ronaldsay, where no known mounds exist near the sites to cloud the picture, suggests that á plus kvern is more probable here too. Indeed, on revisiting the North Ronaldsay and Papay Hookin/g names in 1952, Marwick settles on the ‘river-mill’ interpretation for both places because of the presence of a mill at both sites, dismissing his earlier proposal, for Papay of ‘the burn quoy’ (Marwick, 1952, p. 46).

An area for further research that the present project may be able to inform, once sufficient data has been collected and mapped, is how a comparison of other kví and kvern, and á and hauga elements evolved in Orkney place-names, together with their situations, to see which of the interpretations are more likely.

Corinna Rayner and Matthew Blake

Further Reading

Huser, Thomas Marcus, ‘Fra ‘Færevåg’ til ‘Pier of Wall’? Eldre bebyggelsesnavn på Westray, Orknøyene’ (unpublished dissertation, University of Oslo, 2008).

Lamb, Gregor, Naggles O Piapittem, The placenames of Sanday, Orkney (Orkney: Byrgisey, 1992).

Marwick, Hugh, ‘Antiquarian Notes on Papa Westray’, Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society (Kirkwall: Orkney Antiquarian Society, 1924).

Marwick, Hugh, ‘The Place-Names of North Ronaldsay’, Proceedings of the Orkney Antiquarian Society (Kirkwall: Orkney Antiquarian Society, 1923).

Marwick, Hugh, Orkney Farm Names (Kirkwall: W. R. Mackintosh, 1952).

Sandnes, Berit, From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney (Scottish Place-Name Society, 2010).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply