April 22, 2020, by Rupert Knight

Three domains of literacy

Raising reading and literacy attainment is something that is always at the forefront of educators’ minds. With a myriad of interventions and strategies out there, what is important for raising attainment in these areas?

A group of school leaders and academics came together recently at the University of Nottingham’s School of Education to listen to and engage in discussion with Professor Sue Ellis from the University of Strathclyde. In this blog arising from the event, Sally Betteridge summarises some of the discussions from the morning.

Sue led the session with her recent research into primary reading. The morning focussed on the three domains of literacy that Sue used to enable trainee teachers to try new ways of working with young readers. This highlighted the sorts of literacies that are most valued and neglected in schools, and also opened up discussions around potentially more integrated approaches to teaching literacy. The group also responded to the way that the research Sue drew on positioned teachers as having choice and agency rather than being victims of an overtly performative culture, which is often heavily associated with ‘intervention’ work that happens in schools.

Sue started the morning by asking the group what they wanted to get out of the session.

The replies were to learn about raising attainment; reading for life; to think about reading environments; the culture of reading; changing the reading ethos in school; how to create life-long readers; to be able to draw on the research; reading for pleasure; and ‘catching up’ in ks2.

The discussion then considered the following areas:

What is it that makes reading so difficult?

• Reading is a social practice and it is context-embedded; reading is permeated with many ideologies and policies of the social setting in which it occurs. When we become a reader we are interpreting this context and grappling with the process of reading and the expectations of the social context.

• Reading is a habit of mind; it is not just knowledge and skills and is not a linear process.

• There are lots of ‘regimes of truth’ that surround reading.

• Literacy is a contested space. There are many different ideas about what it means to be literate, the aims of the literacy curriculum, what matters in becoming literate and what should be prioritised or ignored, how to measure it and what methodologies and standards of proof are needed for a robust professional intervention.

• Psychologists often argue about theoretical perspectives and what counts as relevant knowledge and this filters through educational policies and into classrooms unnecessarily.

• There are so many pools of knowledge for teaching; teachers have to look across the whole landscape and make meaning from it for a particular context. Teachers are expected to have the ‘knowledge ability’ needed to orchestrate all the different types of knowledge. This means looking from different perspectives and having professional creativity.

So, what knowledge do teachers need?

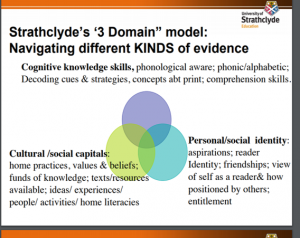

Sue introduced her ‘3 Domain’ model which was at the heart of her ‘kinder literacy intervention’ and had a significant impact on reading attainment:

Sue claimed that the significant aspect that is central to the model is that social class and gender have the biggest impact on reading all over the world. However, our reading practices in school are usually focussed on the top domain – cognitive knowledge skills – and the other 2 domains are often neglected. However if these 2 domains have the biggest impact, then surely these are the ones that need the focus?

The model is deliberately intuitive and lightly specified to avoid the tick-list mentality that interferes with agency. It is a tool to help teachers notice and orchestrate across different kinds of evidence domains – the focus is on educating the whole child. Each domain impacts on the other and they all need the same amount of attention. When we think of ability grouping, this is based on the cognitive domain but what would happen if we looked at this differently and did it through reading identity?

Identity and choice

Identity and choice are central to this; teachers need information about their readers and about reading and books to help their pupils to make these choices. Children in school need to feel part of a reading community. Schools and teachers need to help and guide children to develop and discuss these identities. Some of the things to consider are: do all your children feel the same way about reading? What do their peers think of them? Do they all have a good image of themselves as readers? Are they equally adventurous? What reading networks are they a part of? What’s the sub-culture going on in the classroom and school?

How much of a concept is learned through teacher input, activities, and peer talk will be different for different children so we need to have an equal amount of all these things. Children are architects of their own learning- things can close down learning and open it up.

Sue described a teacher she had met who got books from the library, talked about books, had and gave space to read and space for dialogue about reading – in other words spread his enthusiasm for reading and “attainment shot through the roof.” Teacher enthusiasm has the biggest impact on reading but every teacher needs to do it in their own way and tailored to their own class.

Promoting Networks of Readers

Re-shaping children’s identities as readers is important – what networks are happening in the class and are these having a positive or negative impact on readers’ identities?

Things to think about to create these networks: book blethering; book blessings; creating relaxing social spaces; actively helping readers to find others with similar enthusiasms; putting children in touch with books they like; children recommending books to each other; and the teacher having a sound knowledge of children’s literate and a wide repertoire (which is essential and is one important aspect to consider as a whole school – what knowledge of children’s books do teachers have?). Teresa Cremin’s research on Teachers as Readers has also highlighted the significance of this.

Cultural Capital

Literacy is a socially constructed behaviour and schools tend to assume one version of literacy. We should recognise the different experiences children bring with them to school. Literacy is about your ideas, and what you think literacy is for determines what you learn. How we view reading shapes what we do with it. Teachers need to find out about children’s reading practices at home – what cultural values do they hold? How do they read? How do they view reading – and what is important?

The T.V programme GoggleBox was discussed in terms of the different responses different people have to a ‘text’. Yet all responses are valid and should be valued – this highlighted the significance of how socially and culturally bound reading is. Therefore, for teachers, it is so important to know the children’s backgrounds and what their lives are like. What ‘funds of knowledge’ do the children bring to the classroom with them? This should be seen from an asset model and not a deficit. They will all be engaged in some kind of literacy practices in their lives. We need to find out what these are and recognise them as an asset whilst also considering the barriers. The books that we then choose and recommend need to connect with the children’s cultural capital. Tiny shifts can make a big difference – e.g. mending a children’s bike with a book to guide them and having a conversation at the same time.

I then brought to the discussion the importance of and my experiences of using Philosophy with children as one important way that we find out about children’s lives that wouldn’t necessarily happen elsewhere in the classroom. This has been discussed in a previous blog in this series. In this type of lesson, children openly discuss their experiences linked to a source as this time is dedicated to ‘no right or wrong’ answers so children can engage in dialogue and openly share their opinions, values and aspects of their lived experiences. Philosophy sessions give them a voice to: make meaning and sense of experiences; challenge ideologies; live an examined life; have agency; and think philosophically about the big questions. This is what we want a competent reader to be able do.

Classroom Environment

The group were asked to bring in photographs of the school and classroom walls and environment. These were then discussed using the ‘3 Domain model’. The discussion was around the messages that the English displays and reading areas give out. The group fed back that the displays were heavily focussed on the ‘cognitive’ domain and much less on the other two.

Questions to Ponder:

• How do we find out about the children’s reading identities?

• How do we create reading communities in the classroom and allow children to blether about books, recommend to each other, choose different types of books and be excited about books? And how much quality time are we dedicating to reading for pleasure?

• If teacher enthusiasm has the biggest impact, how do we share what we are reading and have the knowledge of quality children’s literature, keep afloat of new literature and be equipped to recommend books to children based on their personal reading identities? And an important aspect to this is, are we having dedicated time to a whole class text where the teacher can just enjoy reading to the class?

• What have we got space to find out about children’s social and cultural capital? And are we seeing their reading backgrounds as an asset or a deficit?

• Can we use the 3 domain model for quality reading assessment that looks at all the aspects of being a reader and what impact will doing this have?

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply