September 22, 2016, by Rupert Knight

Understanding comprehension

In the wake of the controversy surrounding this year’s KS2 reading test, reading has been very much in the spotlight once again, as seen in this recent TES story.

In this post Jane Medwell explores comprehension as an important aspect of that reading process.

What is comprehension?

Comprehension is what turns “decoding” into “reading”. Understanding the literal meaning of a text is a start to comprehension- but it is not enough. Readers need to be able to understand texts that don’t just say what they mean- and mean things that they don’t say.

Hugely improved sores on the PSC (phonics screening check) have told us that children can do decontextualized phonics (and that teachers are brilliant at preparing them for the check). But this hasn’t produced a great increase in later reading level among the seven year olds who passed the phonics test, as this report from this summer suggests.

There is more to reading than just decoding but if only it was clearer what reading comprehension is.

The Simple View formula presented by Gough and Tunmer in 1986 is:

Decoding (D) x Language Comprehension (LC) = Reading Comprehension (RC).

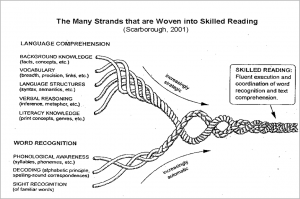

And this view underpins our current approaches to teaching reading. A more complex way of presenting this “simple” view is to think of reading as comprising a number strands woven together. Scarborough (2001) expressed this as a diagram:

This model compares skilled reading to a rope, which consists of many different strands that are essential for the rope (skilled reading) to come together. Let’s look at each “strand”:

Language Comprehension:

- Background Knowledge -This refers to the knowledge a reader already has about the information being read which needs to be applied in order to make sense of this new information. The knowledge about the world which children possess is, it seems, fairly crucial to them reading effectively.

- Vocabulary – This refers to the breadth of a reader’s vocabulary. Obviously the more words a reader knows in a text, the more fluent his/her reading of that text is likely to be.

- Language Structures – A reader needs at least an implicit understanding of how language is structured, that is, grammar. The debate has been about whether that knowledge needs to be explicit. Most children (and adults) sense when a sentence is not grammatically correct without being able to explain what the problem is.

- Verbal Reasoning – Readers need to be able to make inferences and construct meanings from the text: that is, they need to be able to THINK logically about what they read in they are to understand it, and its implications.

- Literacy Knowledge – It sounds obvious, but it is clearly important for child readers to understand concepts of print such as reading from left to right and top to bottom, how to hold a book, and that full stops complete one sentence (unit of meaning) before the text moves on. These things do not work in the same way in other languages, so they probably need to be taught somehow to English-speaking (and reading) children.

Word Recognition:

- Phonological Awareness – This refers to the awareness a reader has of the sound systems in language, including knowledge of syllables, and sentence intonation (a rise in voice when asking a question, for example). Knowledge and experience of rhymes seems especially important in developing this awareness.

- Decoding– This includes an understanding of the alphabetic principle, that is that a letter of the alphabet represents a sound, and that these letters/sounds can be blended together to make words. This is somewhat trickier in English than in some other languages. English has about 44 sounds (phonemes) but only 26 letters in the alphabet. Thus the relationship between letters and sounds cannot be one to one.

- Sight Recognition – Some words are recognised when reading without the reader needing to decode them: you just know them. Research tells us that, in fact, most adult reading is like this. It is quite rare for us to have to read words we have never seen before, and thus do not know. Children need to build up their repertoires of sight words and the more they can read by sight, the more efficient their reading becomes.

These “strands” all work together to enable skilled reading. The strands develop over time and with more teaching and experience. The “Word Recognition” strands become more and more automatic with practice. Fluent readers will simply not be aware of these things happening – unless they encounter a problem.

In the case of the “Language Comprehension” strands, there will be a movement towards becoming more strategic in their use. Readers will become more aware of what they are doing and more in control of it. Of course, the development of comprehension is not time-limited. We all become better, more efficient and more subtle readers as we get older, more experienced, and meet more complex texts. However, just as the skills of word recognition will develop and grow in response to teaching, so too will all aspects of comprehension.

There are many ways of approaching this, and some strong underlying principles. These will be the subject of our next blog on this topic. In the meantime, you may find this model of comprehension skills interesting:

We’d like to hear your views. Which aspects of reading are most challenging for your learners?

References

Gough, P. B. & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6-10.

Scarborough, H. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. Pp. 97-110 in S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.) Handbook of Early Literacy. NY: Guilford Press.

I enjoy what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and coverage!

Keep up the great works guys I’ve added you guys to my personal blogroll.

Incredible points. Great arguments. Keep up the amazing work. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gran_Canaria/074/5