November 9, 2017, by Lindsay Brooke

Nottingham remembers its part in the DNA discovery

Tomorrow the University of Nottingham celebrates the 70th anniversary of the discovery by a young PhD student, J Michael Creeth, of hydrogen bonds in DNA. The event will be attended by leading academics in the field.

Fifteen years ago the scientific community celebrated the 50th anniversary of the discovery of DNA by Crick and Watson. But Nottingham had its own part to play in the DNA story.

An interview with J Michael Creeth

In 2003, to mark Nottingham’s part in the race to identify the ‘code of life’, Emma Thorne, one of the Media Relations Managers at the University of Nottingham, travelled to Shropshire to the home of J Michael Creeth to talk to him about the research he carried out at Nottingham.

Looking back, Emma recalled: “I’ve interviewed many people over the course of my career, but Dr Creeth was one of those truly remarkable characters that you tend to remember, even after so many years.

“Shropshire was a little farther afield than I would usually travel for a Newsletter feature and I can remember arriving late and a little flustered, having become horribly lost along the way. Dr Creeth put me immediately at ease – he sat me down with a cup of tea and proceeded to tell me one of the most fascinating stories that I had ever heard in connection with the university.

“Despite his brilliance and eminence, he was a very modest man and seemed genuinely delighted that someone would make the time and effort to travel to see him and talk about his career. And there’s always something rather lovely about listening to the recollections of someone about a time in their life which they still so obviously look back on with great pride and affection.”

Here’s a transcript of Emma’s article published in the University’s ‘Newsletter’ in 2003.

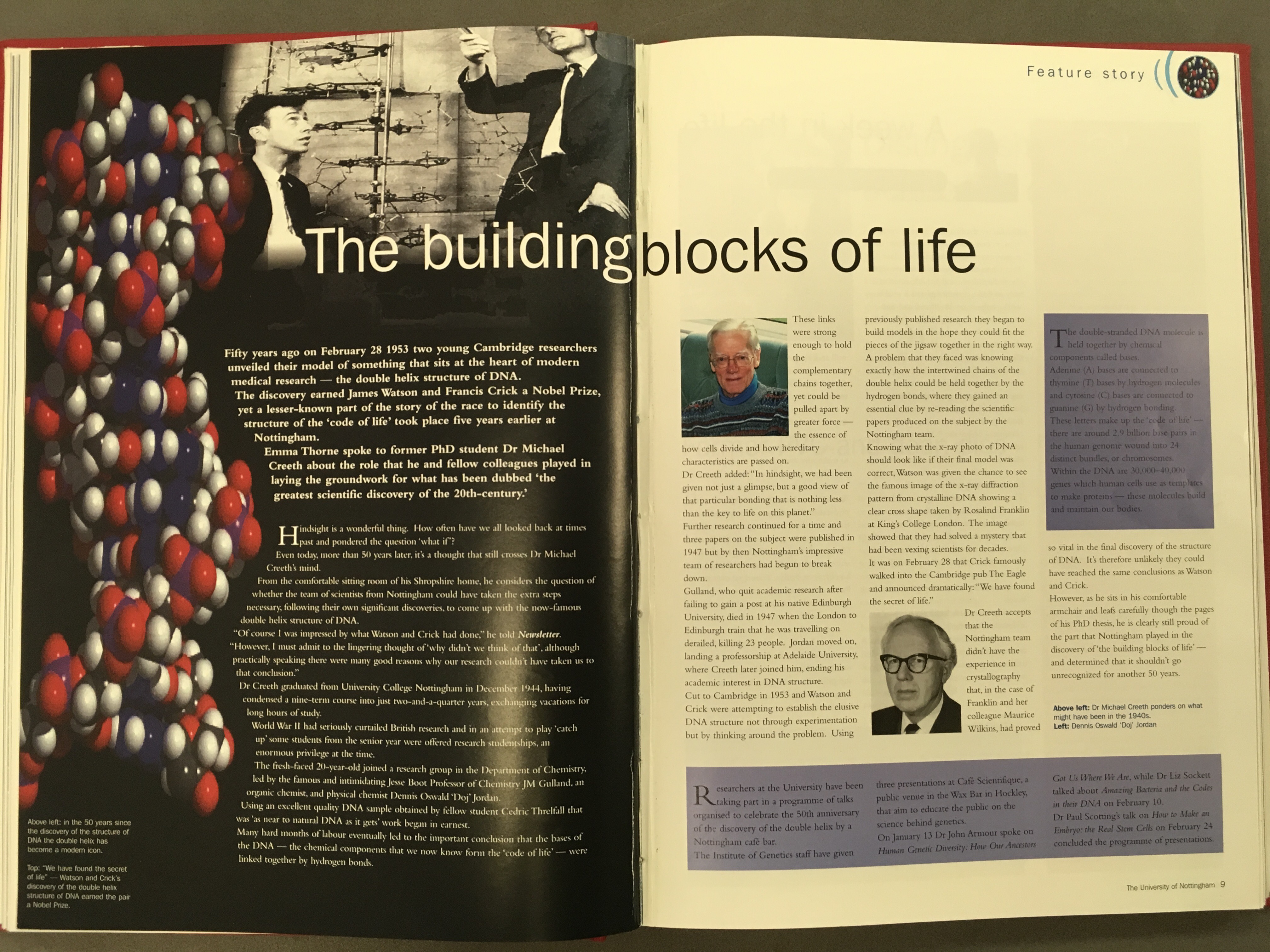

The building blocks of life

Fifty years ago on February 28 1953 two young Cambridge researchers unveiled their model of something that sits at the heart of modern medical research – the double helix structure of DNA.

The discovery earned James Watson and Francis Crick a Nobel Prize, yet a lesser-known part of the story of the race to identify the structure of the ‘code of life’ took place five years earlier at Nottingham.

Emma Thorne spoke to former PhD student Dr Michael Creeth about the role that he and fellow colleagues played in laying the groundwork for what has been dubbed ‘the greatest scientific discovery of the 20th century.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. How often have we all looked back at times past and pondered the question ‘what if’?

Event today, more than 50 years later, it’s a thought that still crosses Dr Michael Creeth’s mind.

From the comfortable sitting room of this Shropshire home, he considers the question of whether the team of scientists from Nottingham could have taken the extra steps necessary, following their own significant discoveries, to come up with the now-famous double helix structure of DNA.

“Of course I was impressed by what Watson and Crick had done.” He told Newsletter.

“However, I must admit to the lingering thought of ‘why didn’t we think of that’, although practically speaking there were many good reasons why our research couldn’t have taken us to that conclusion.”

Dr Creeth graduated from University College Nottingham in December 1944, having condensed a nine-term course into just two-and-a-quarter years, exchanging vacations for long hours of study.

World War II had seriously curtailed British research and in an attempt to play ‘catch up’ some students from the senior year were offered research studentships, an enormous privilege at the time.

The fresh-faced 20-year-old joined a research group in the Department of Chemistry, led by the famous and intimidating Jesse Boot Professor of Chemistry JM Gulland, an organic chemist, and physical chemist Dennis Oswald ‘Doj’ Jordan.

Using an excellent quality DNA sample obtained by fellow student Cedric Threlfall that was ‘as near to natural DNA as it gets’ work began in earnest.

Many hard months of labour eventually led to the important contribution that the basis of the DNA – the chemical components that we now know form the ‘code of life’ – were linked together by hydrogen bonds.

These links were strong enough to hold the complementary chains together, yet could be pulled apart by greater force – how cells divide and how hereditary characteristics are passed on.

Dr Creeth added: “In hindsight, we had been given not just a glimpse, but a good view of that particular bonding that is nothing less than the key to life on this planet.”

Further research continued for a time and three papers on the subject were published in 1947 but by then Nottingham’s impressive team of researchers had begun to break down.

Gulland, who quit academic research after failing to gain a post at his native Edinburgh University, died in 1947 when the London to Edinburgh train that he was travelling on derailed, killing 23 people. Jordan moved on, landing a professorship at Adelaide University, where Creeth later joined him, ending his academic interest in DNA structure.

Cut to Cambridge in 1953 and Watson and Crick were attempting to establish the elusive DNA structure not through experimentation but by thinking around the problem. Using previously published research they began to build models in the hope they could fit the pieces of the jigsaw together in the right way. A problem that they faced was knowing exactly how the intertwined chains of the double helix could be held together by the hydrogen bonds, where they gained an essential clue by re-reading the scientific papers produced on the subject by the Nottingham team.

Knowing what the x-ray photo of DNA should look like if their final model was correct, Watson was given the chance to see the famous image of the x-ray diffraction pattern from crystalline DNA showing a clear cross shape taken by Rosalind Franklin at Kings College London. The image showed that they had solved a mystery that had been vexing scientist for decades.

It was on February 28 that Crick famously walked into the Cambridge pub The Eagle and announced dramatically: “We have found the secret of life.”

Dr Creeth accepts that the Nottingham team didn’t have the experience in crystallography that, in the case of Franklin and her colleague Maurice Wilkins, had proved so vital in the final discovery of the structure of DNA. It’s therefore unlikely they could have reached the same conclusions as Watson and Crick.

However, as he sits in his comfortable armchair and leafs carefully through the pages of his PhD thesis, he is clearly still proud of the part that Nottingham played in the discovery of ‘the building blocks of life’ – and determined that it shouldn’t go unrecognised for another 50 years.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply