May 4, 2020, by Emma Rayner

Fighting the war? Remembering twentieth century conflicts and responding to Covid-19

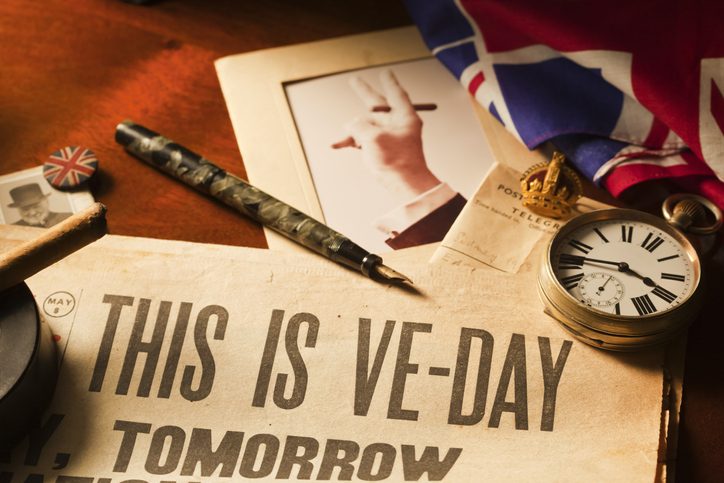

In the run up to VE Day @75 on Friday 8th May 2020, Dr Ross Wilson shares his thoughts on the references to war in contemporary reporting of the Covid-19 pandemic and how wartime experience could guide, inform and warn us. His free online talk about the trenches of WW1 takes place live at 5pm on Tuesday 19th May and is bookable here.

The appearance of ‘war rhetoric’ during the advance of Covid-19 has been noticeable in Britain as public figures and politicians attempt to assure and inspire the public. It is not uncommon for the virus to be referred to as ‘the enemy’, to describe our situation as ‘in the trenches’, for critical commentary stating that our ‘front line’ workers are left ‘in no man’s land’ and need to be ‘mobilised’, or, for wartime references to be deployed as we are informed that ‘it’ll be over by Christmas’ or comforted that ‘we’ll meet again’.

Indeed, a survey of the newspaper articles since January 2020 would demonstrate how the conflicts of the twentieth century are embedded in the way in which we deal with national crises in Britain. This use of language to frame our expectations and identities has been critiqued as a political tool, but wartime experience can be a useful guide into understanding how individuals and groups cope under pressure. Beyond the rhetoric, there are important reminders of how society acts, mourns and remembers to adjust to trauma, fear and uncertainty that has defined our world in recent weeks.

Wartime experience

During both world wars, communities across Britain were faced with an unprecedented upheaval. The Defence of the Realm Act of 1914 and the Emergency Powers Act of 1939 curtailed social life by changing the opening hours of pubs, forbidding some public gatherings and restricting travel across the country. As the scale of the conflict increased, volunteers and eventually conscripts were asked to fight for ‘God, King and Country’. Men and women were part of this effort as they also worked in factories and fields whilst children participated in the various charitable drives to raise money. Alongside this work were schemes to help the destitute and elderly as well as to protect the vulnerable within society.

This mobilisation of society was encouraged by the British Government, but it was enacted by people on the basis of belonging to a local community. When faced with challenges, perceived or real, the response of groups is to form or reinforce bonds of allegiances, to create an ‘imagined community’ which offers reassurance during periods of apprehension. The formation of formal and informal networks that offer care, support and comfort in the last few months is demonstrated in this process. Inspired by the commitment to ‘Protect the NHS’, we have formed networks of compassion which support one another.

This empathy brings criticism of those not conforming to this sense of belonging but also fear and paranoia of others. During the First World War and the Second World War, public opprobrium was reserved for those accused of profiteering. Landlords or businesses who sought to raise rents or benefit from the strained economic circumstances were subject to pillory within the public as anyone departing from the norm was regarded as undermining confidence. However, companies were also physically attacked for presumed links to the enemy as rumour and hearsay would dominate within a heavily censured media. The premises of German British businesses had windows smashed by mobs after reports of the sinking of the passenger liner, The Lusitania, in 1915. Suspected ‘aliens’, innocent of any specific crimes, were also arrested and detained in the interest of public order throughout both world wars.

As we form bonds within communities, we also begin to police these connections to maintain the groups that we have formed. This can take the form of outrage and anger over companies seeking to win favourable terms during the Covid-19 crisis. The criticism faced by Virgin Atlantic, Wetherspoons or Sports Direct and their operation of business or attempts to secure public funds demonstrates how we set new boundaries on what is acceptable behaviour during periods of uncertainty. The circulation of ‘fake news’ purporting cures or suggesting 5G network towers as the source of infection also indicates how connections that stoke fear can also lead to actions that damage and disturb the physical health and democratic structures of the body politic.

Remembering and mourning

During the world wars, local communities would strengthen bonds by acknowledging the service and sacrifice of individuals or groups. The reports of charity events to raise money or notices of the deaths of men and women would be regular features of regional newspapers. This acted as a reminder of how during wartime, we identify with others, share their experiences and value their contributions. With the daily reports of the sacrifices made by NHS staff, the events created to support others or the ways in which individuals have raised millions for charities, our sense of belonging and participation is affirmed.

The narratives of sacrifice offer a reminder how others are working for us. During the First World War, it was not uncommon to see temporary memorials created on streets where resident or family member had died. As we draw rainbows or leave messages of support for health workers, we also participate in these acts of community that serve to connect us to those who are directly involved in tackling the outbreak of Covid-19.This memorialisation is perhaps the most important point of connection to wartime experience.

After the First World War, monuments were erected across Britain and on the former battlefields by local committees and by the government to name the individuals who died. With the end of the Second World War, new names are added to these memorials and new monuments to their sacrifice are created. These are the sites where communities mourn and remember the dead. They are also sites where we sometimes forget, too.

The memory of the global conflicts of the twentieth century in Britain tends to neglect their international aspect and how men and women from across the world participated and gave their lives to help others. The current Covid-19 crises clearly indicates how our heath service depends on a global community which must not be forgotten or lost after the end of this pandemic.

With the conclusion of both wars, what marked British society was the ‘communities of mourning’ that were created as people were brought together by what they had experienced. This informal remembrance was not marked by monuments or memorials, it was the shared knowledge of how when faced with uncertainty, individuals and groups seek to find ways to cooperate and form bonds that allow us to participate and engage.

Forming new communities

This is the most significant event in many peoples’ lifetimes and the impact of Covid-19 will be felt across our economy for decades. It will also be an event that is remembered by communities through shared experience and the language we use. The terms ‘social distancing’ and ‘lockdown’ have become part of our daily lives. In time, we will remember these events in the same way as the wars of the twentieth century have been recalled; as a means of adapting and adjusting to the uncertainty of the world.

Rather than just convenient references, wartime allusions can remind us, encourage us and warn us of how we act when we are faced with adversity.

Dr Ross Wilson is Director of Liberal Arts in the School of Cultures, Languages and Area Studies, Faculty of Arts. His free online talk detailed below takes place live at 5pm on Tuesday 19th May and is bookable here.

How British soldiers coped on the battlefields of France and Flanders during the First World War

In this talk we explore with Dr Ross Wilson how the soldiers of the British Army adapted to endured the experience of the Western Front: morale, camaraderie, discipline and courage – “Tommifying the Western Front”.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply