November 1, 2018, by Emma Lowry

Nottingham in the War – “Beloved” Bulleid: the Nottingham engineer helping the war effort

Under the leadership of Professor Charles Bulleid, the Engineering Department at University College Nottingham, (now the University of Nottingham) made extensive contributions to the war effort.

The First World War was a crisis that was felt particularly keenly in colleges and universities. These institutions, which had been full of healthy young men, were nearly emptied once the call for volunteers rang out at the end of summer 1914. These young men, who became immortalised as ’tommies’, remain the focus of many people’s thoughts about the war. What is less well-known is that the people who taught these students were also called upon to contribute and to make their research expertise available to the war effort.

Perhaps the most significant of Nottingham’s academic experts was Charles Henry Bulleid, Professor of Engineering, who brought his skills to the problems of making armaments for use on both land and sea. Beginning in 1915, Bulleid carried out work, both in and out of the College, that proved essential for winning the war.

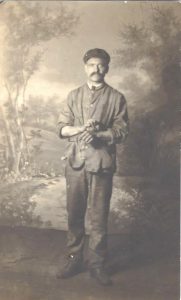

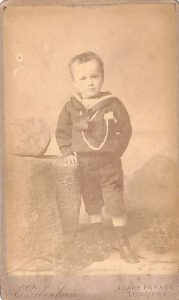

Bulleid was born in Hatherleigh, Devon in 1882, the youngest of eight children to Samuel and Mary Bulleid. Charles was educated at Exeter Grammar School in 1889, after securing a full scholarship at just six years of age. After obtaining an open scholarship he went on to study at Trinity College, Cambridge from 1900, where he took First Class Honours in the Mathematics Tripos and Mechanical Sciences. He then spent two years lecturing in the Engineering Laboratories at Trinity College.

Bulleid was born in Hatherleigh, Devon in 1882, the youngest of eight children to Samuel and Mary Bulleid. Charles was educated at Exeter Grammar School in 1889, after securing a full scholarship at just six years of age. After obtaining an open scholarship he went on to study at Trinity College, Cambridge from 1900, where he took First Class Honours in the Mathematics Tripos and Mechanical Sciences. He then spent two years lecturing in the Engineering Laboratories at Trinity College.

Leaving Cambridge for industry, he served an engineering apprenticeship in the locomotive department of the Midland Railway in Derby before taking his first role as assistant to the Technical Manager at Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company in Wallsend-on-Tyne, Newcastle. In late 1912, Bulleid returned to academia as Professor of Engineering at University College Nottingham.

Bulleid was still in post at Nottingham in 1915, which proved to be a turning point in the war. It was then that the fighting on the Western Front had settled into a position of stalemate. By the spring of that year, military commanders were issuing warnings that their troops were using ammunition at a faster rate than they were being supplied with it. These criticisms, which caused a scandal in the press, led to the Government establishing the Ministry of Munitions, under David Lloyd George, with the sole mission of ensuring that the nation’s resources were deployed in the production of arms. These resources included the nationwide network of colleges and universities.

Although a huge programme of factory-building was undertaken in late 1915, most of the dedicated munitions factories would not be ready until early 1916. These included two Nottinghamshire installations, No.6 Filling Factory at Chilwell and the National Projectile Factory, built and operated by the engineering firm Cammell Laird, near Kings Meadow.

Every week of delay created further risk that British soldiers would run out of ammunition. In an effort to save time, Bulleid, a member of the Nottingham Munitions Committee, opened the College’s engineering workshops for staff from Cammell Laird to complete essential testing of equipment while the factory was still being constructed. At the same time, he supervised the training of munitions workers at the College and oversaw the recruitment of a female instructor for this work, ensuring that the new factories would have a trained workforce ready to go as soon as the buildings were ready.

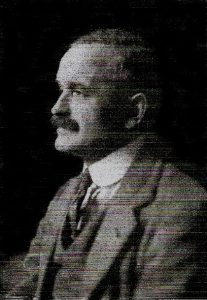

Bulleid’s relationship with the Ministry of Munitions continued for several years. His expertise was considered so essential that he could no longer support its work from his office in the College and so, in January 1917 he was appointed General Manager of the National Projectile Factory. Although this would have been highly demanding work, he remained in post as professor, being granted special leave, with the condition that he continued to ‘undertake the general responsibility of the Department and conduct classes one morning and one evening per week’.

Bulleid’s relationship with the Ministry of Munitions continued for several years. His expertise was considered so essential that he could no longer support its work from his office in the College and so, in January 1917 he was appointed General Manager of the National Projectile Factory. Although this would have been highly demanding work, he remained in post as professor, being granted special leave, with the condition that he continued to ‘undertake the general responsibility of the Department and conduct classes one morning and one evening per week’.

Bulleid’s factory specialised in the production of 9.2in and 6in shells and making 18 pounder guns. During his tenure, it boasted a workforce of around 6,000 people, just over half of which were women. Output was strong, with a weekly delivery of 13,000 of the 6in shells and 5,000 of the 9.2in variants.

After a year at the projectile factory, Bulleid was permitted to take a further leave of absence to take the role of Chief Engineer of the Admiralty School of Mines at HMS Gunwharf in Portsmouth, an important appointment that was to last for the remainder of the war. The School of Mines was responsible for developing and maintaining naval mines and torpedoes and for devising countermeasures against enemy use of similar weapons. The precise nature of Bulleid’s work for the admiralty is not known, but he is known to have had experience with the engineering firm Parson’s, whose turbines had a notable marine application.

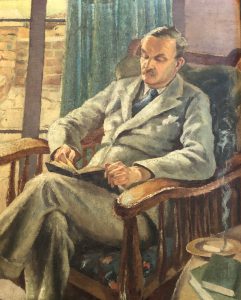

At the end of the war, Bulleid returned to his duties at the College. His post-war work included researches on the fatigue of cast iron and on the vibration of shafts. He served the Institution of Mechanical Engineers as Chairman of the East Midlands Branch, and a Member of Council, and was one of the assessors for the National Certificate Scheme for several years. He was also an Associate Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers and a Member of the Institute of Metals. In 1942 he was awarded the Herbert Ackroyd Stuart Prize, and was the author of several technical papers. His expertise was often sought by industry and Bulleid frequently acted as an expert witness and consultant to local firms.

One past student fondly recalled his university years in the early 1940s, describing Bulleid as a “shabbily-dressed, chain-smoker of Woodbines and a beloved eccentric with a mercurial mind”. “All his lectures were virtuoso performances and extempore, such that all the students felt they were sharing an adventure for the first time.”

He retired in 1949 and was made professor emeritus in recognition of his services to the Department of Engineering. He was awarded the OBE for his war service in 1918. He died on 29 June 1956, aged 74, leaving a proud legacy of having built the Faculty of Engineering “from very small beginnings to that of a flourishing university” (Nature, 1949).

Professor Charles Henry Bulleid OBE MA 1882-1956

Special thanks to Liz Gross (granddaughter of Charles Bulleid), Mike Noble, from the Department of History and Professor Mike Clifford, Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham for their content contributions and the images included in this post.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply